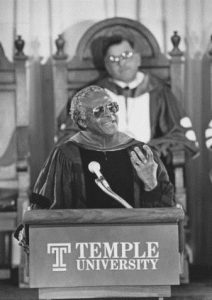

The Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Philadelphia (JCRC) was established by B’nai B’rith in January 1939, but was originally known as the Philadelphia Anti-Defamation Council (PADC). The organization changed its name in May 1944, to better reflect its dual mission to fight anti-Semitism and organized bigotry, as well as to promote intergroup understanding and cooperation. Although the JCRC developed into an organization that worked to advance both of these goals, the earliest records show their focusfrom 1939 through the end of the Second World War was on investigating and combatting anti-Semitism.

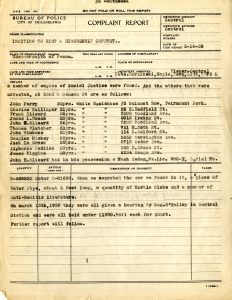

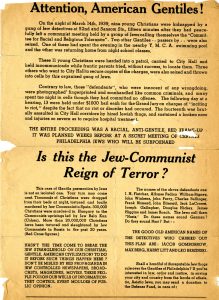

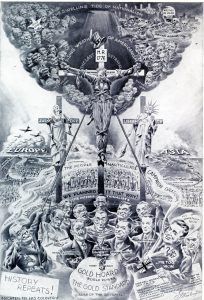

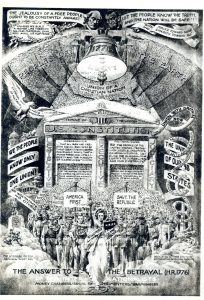

Prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, conspiratorial ideas regarding Jews increasingly became intermixed with an isolationist and nativist sentiment that hoped to keep America strictly neutral in the growing conflict in Europe and Asia. A graphic example of this came to the attention of the PADC on April 17, 1941.

Initially referred to as the “new pro-Nazi circular,” correspondence shows that Maurice Fagan, executive director of the PADC, was in contact with the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and other groups who were investigating its appearance in Philadelphia. An ADL contact revealed that a large number of these circulars were sent to “H. L. Smith” of 2218 Pine Street by “M. Slauter” of 715 Aldine Ave., Chicago. A few days later, Fagan learned that the “Uncle Sam crucifixion circular” was the “brain child” of Newton Jenkins of Chicago and that there were reports of the circular appearing in Oregon and New York. A memorandum from April 24, described 715 Aldine Ave. as a “clearinghouse for anti-Semitic material” and connected Newton Jenkins with Elizabeth Dilling, a right-wing activist and supporter of isolationism.

An April 27 American Jewish Committee report, orchestrated by George Mintzer, details an investigation of the 715 Aldine address and the individuals associated with the case. While the address turned out to be a boarding house and M. Slauter to be a fictitious name, the investigator discovered the circular was printed by John Winter, co-owner of a Chicago printing company that had previously been investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation for connections with the German American Bund, the National German-American Alliance, and other “front organizations associated with the Nazi movement.”

A second circular began appearing in May that shared the same artistic and thematic style as the first. A May 15 letter from Joseph Roos to Maurice Fagan and others, states that Gustav A. Brand was very likely the artist behind both circulars. Roos states that he knew Brand well and that Brand was a former Chicago City Treasurer who “has constantly been under fire because of his strong Nazi language.”

On May 29, Maurice Fagan sent a letter to the Philadelphia office of the F.B.I. with an update on the investigation into the circulars. This letter appears to be the last action taken on this case, but the records of the JCRC contain many other examples of PADC investigating and exposing cases of anti-Semitism in the Greater Philadelphia region.

–Kenneth Cleary, Project Archivist, Philadelphia Jewish Archives Collection, SCRC

This is the third post of an occasional series highlighting the work of Philadelphia’s Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC). The records of the JCRC, housed in Temple University Libraries’ Special Collections Research Center, are currently being processed and will be available for research in 2018.