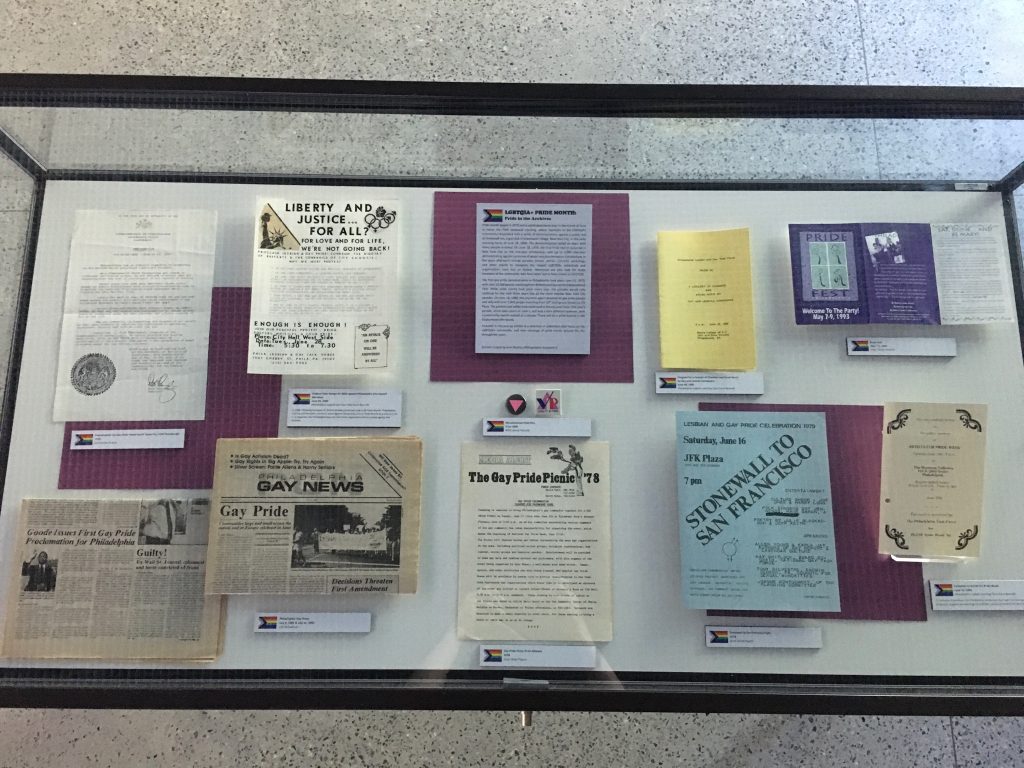

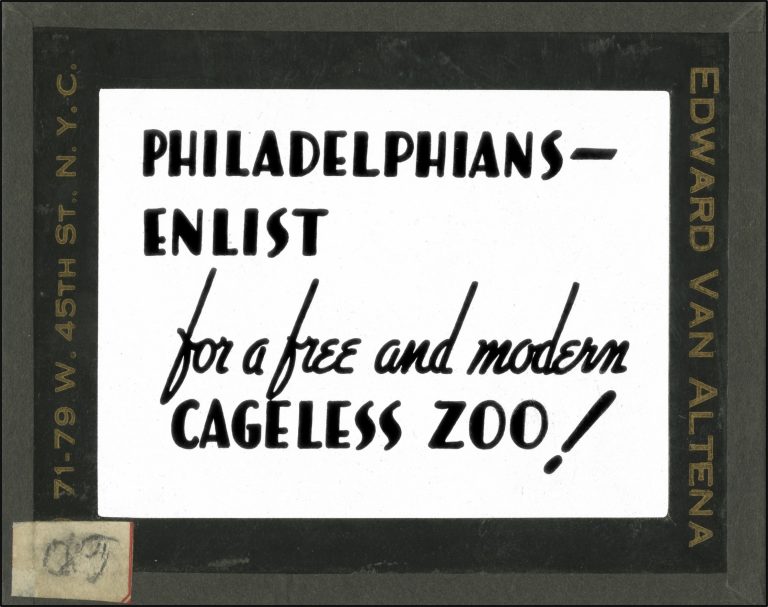

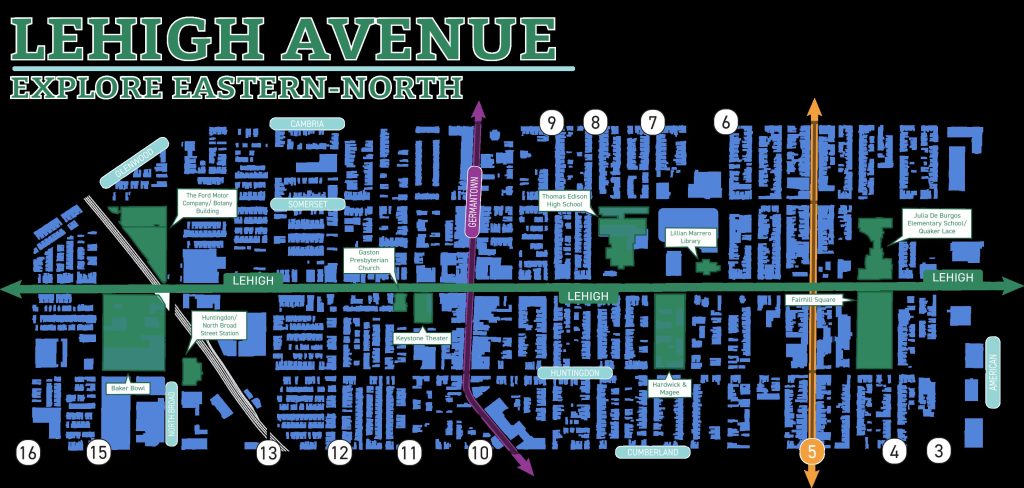

Philadelphia’s African-American population grew during World War II and in the decades that followed. Exacerbated by racial segregation, this population growth led to a severe housing shortage among the city’s Black population. In response, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Philadelphia Branch, and the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations led efforts to combat racial discrimination and segregation in housing. Records documenting these efforts are on display in the latest Special Collections Research Center pop-up exhibit in the reading room.

Fair housing efforts of this period at first focused mostly on appeals to principles of justice and fairness in order to reduce barriers to housing for African Americans. In the 1950s and 60s, Philadelphia became an epicenter for fair housing activism. Notably, in 1951 voters approved a Home Rule Charter, which banned discrimination in public employment, public accommodations, and housing. The new charter also created the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations (CHR), whose mandate was to enforce the charter’s prohibitions on racial segregation. Under Mayor Joseph Clark, the first Democrat to serve as mayor (1952- 1956) since the nineteenth century, the city instituted reforms on a wide variety of issues, including reforms aimed at fighting racial housing discrimination.

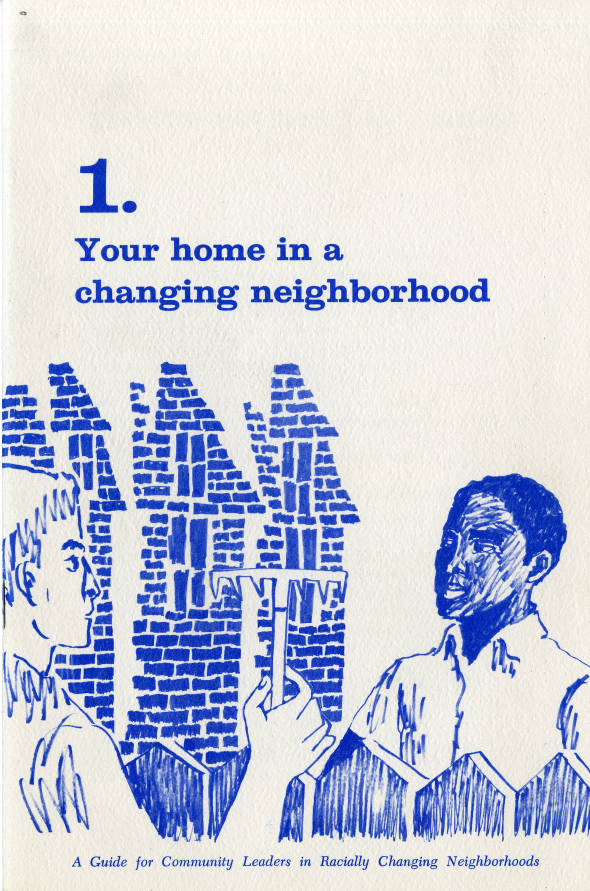

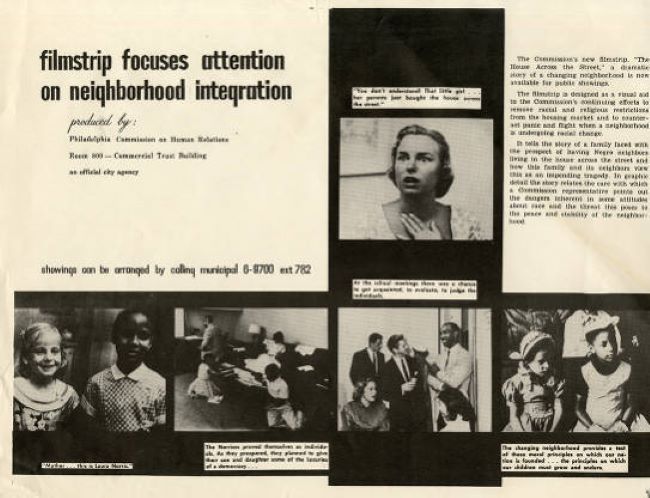

The CHR provided education about housing integration through publications, films, and neighborhood programs, a few of which are on display. Despite these efforts, racial discrimination, tension, and white flight continued. In response, the commission shifted its focus to crafting and supporting fair housing legislation more broadly at the local and state level.

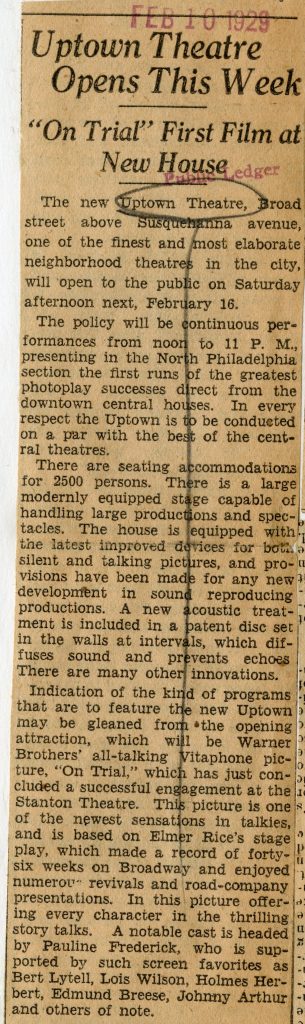

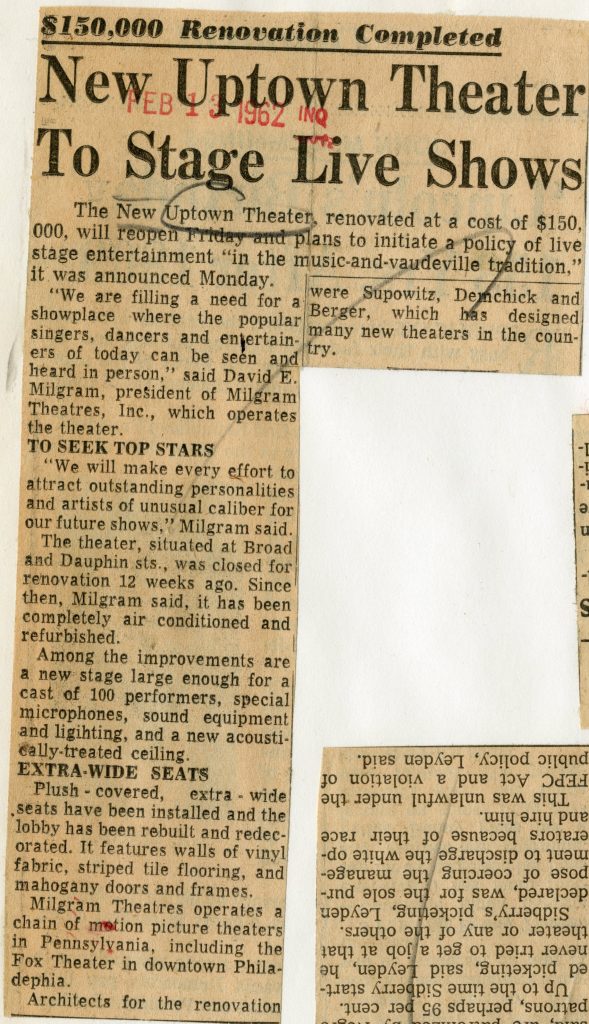

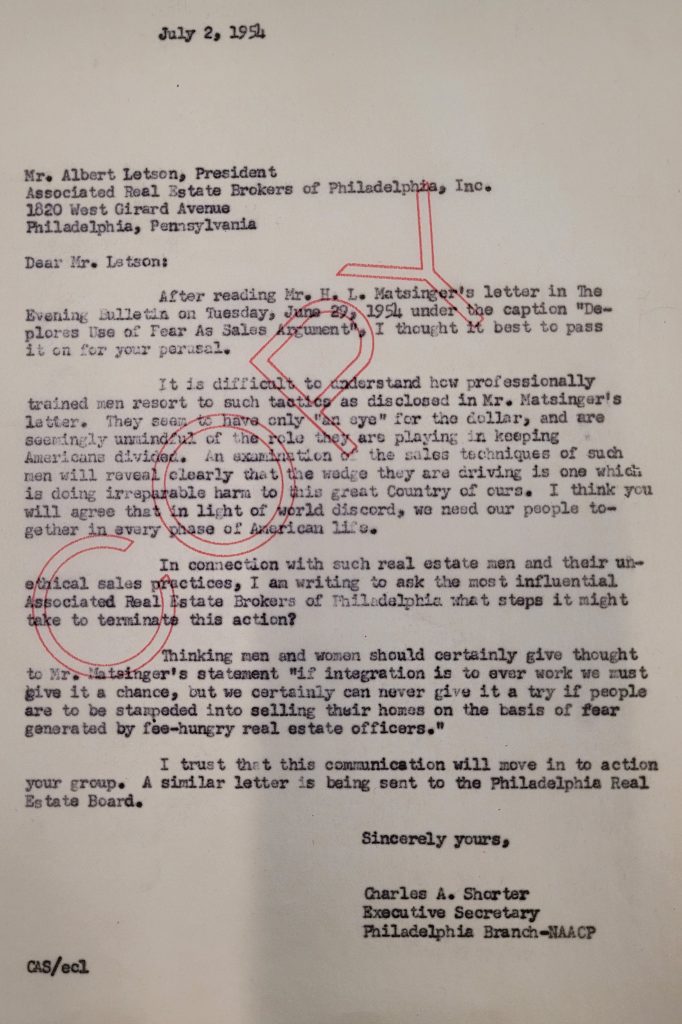

The NAACP, Philadelphia Branch, under the leadership of Charles A. Shorter, also made important strides in extending civil rights during this period. Shorter led successful efforts to force department stores to hire black clerks, end segregated seating in Philadelphia theaters, and integrate the Philadelphia Real Estate Board and the Pennsylvania Parole Board, among other accomplishments in this era. In 1953, the Philadelphia Branch was awarded the Thalheimer Award, the NAACP’s top award given to branches for outstanding achievements.

Included in this pop-up exhibit are a selection of items from the NAACP, Philadelphia Branch Records, the Urban Archives Pamphlet Collection, and clippings and photographs form the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photograph Collection documenting efforts by CHR and the NAACP Philadelphia Branch to combat housing segregation and white flight during the economic and demographic changes of the post-war years in Philadelphia.

–Josue’ Hurtado, Coordinator of Public Services, SCRC