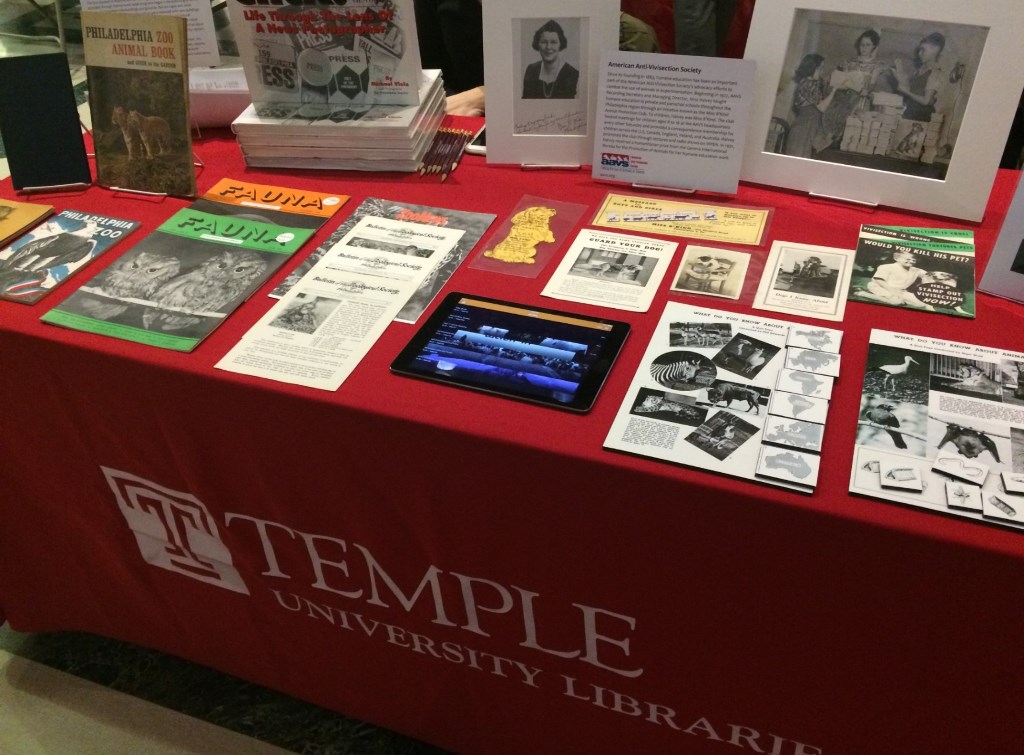

Each year in October, the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) celebrates American Archives Month through dedicated programming that raises awareness about the value of archives. This year, the SCRC participated in the Archives Month Philly sponsored event, “Animals in the Archives,” at the Free Library of Philadelphia Parkway Central Library. The event featured over a dozen Philadelphia-area institutions including the Chemical Heritage Foundation, Presbyterian Historical Society, The Stoogeum, and the William Way LGBT Community Center, each of which brought along archival material and hands-on activities, all with animal related content.

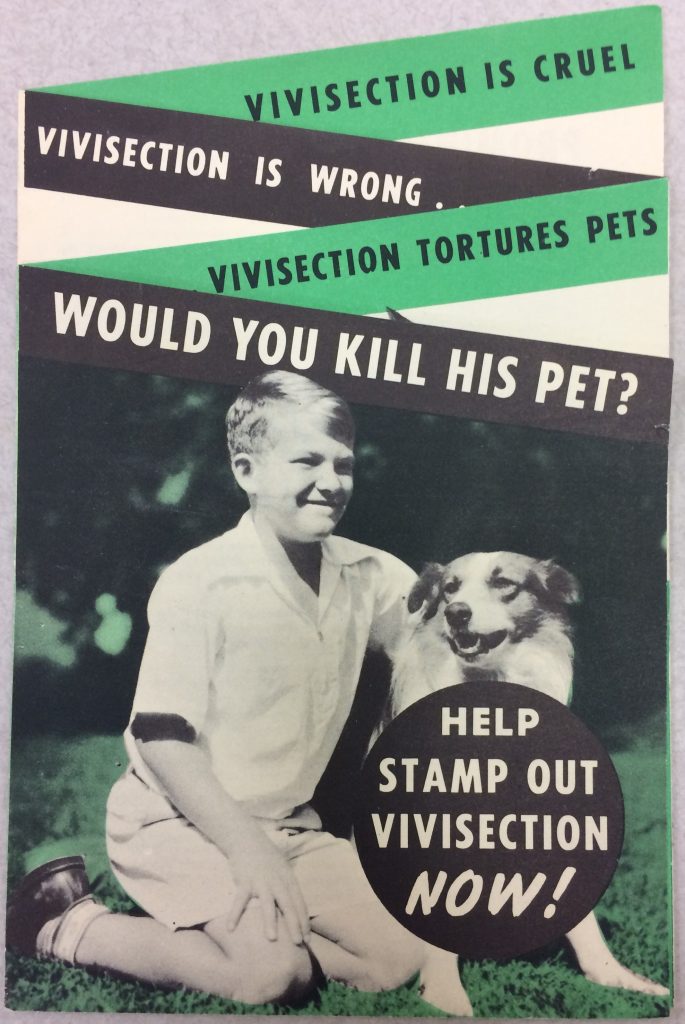

At the event, the SCRC featured publications, photographs, and printed materials from the archives of two local organizations founded in the 19th century, The Philadelphia Zoo and the American Anti-Vivisection Society (AAVS). Throughout their existence, “America’s First Zoo” and AAVS have sought to educate the public about animals and animal welfare through organized programs. One of those programs was the Miss B’Kind Animal Protection Club, started in 1927 by AAVS Recording Secretary and Managing Director, Nina Halvey.

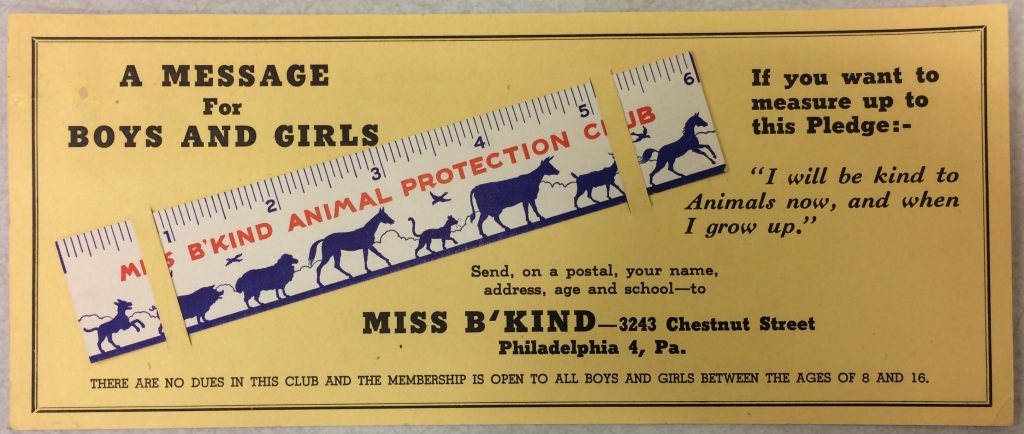

Halvey taught humane education in private and parochial schools throughout the Philadelphia region as part of the AAVS’ effort to combat the use of animals in scientific experimentation. The club also hosted meetings for children ages 8 to 16 at the AAVS headquarters every other Saturday and provided a correspondence membership for children across the U.S, Canada, England, Ireland, and Australia. Club members pledged “I will be kind to animals now and when I grow up.” Halvey promoted the club through lectures and a radio show series on WPEN called “Dogs I Know About.” In 1931, Halvey received a humanitarian prize from the Geneva International Bureau for the Protection of Animals for her humane education work related to the Miss B’Kind Club.

To learn more about the Miss B’Kind Animal Protection Club and the historical records of the AAVS, including preserved versions of the organization’s website, contact the SCRC at scrc@temple.edu

Jessica M. Lydon, Associate Archivist, SCRC