Temple University Libraries was pleased to be a part of the celebration of the 150th anniversary of the founding of Grace Baptist Church (now of Blue Bell), recognizing the deep connections the University has with that congregation.

In the 1870s, the fledgling congregation pitched its tent and then built its first building at the corner of Berks and Marvine—now under Temple’s Gladfelter Hall. In 1882, they called the Rev. Russell Conwell from a small congregation in Lexington, Massachusetts, to become their pastor and changed the history of Philadelphia. Conwell’s ability to inspire, to build, and to create and recreate institutions included not only Temple University, but also Greatheart and Samaritan hospitals and the Samaritan Aid Society, among others. Starting in 1884, Grace Baptist Church facilities hosted the first night classes of what would eventually become Temple University.

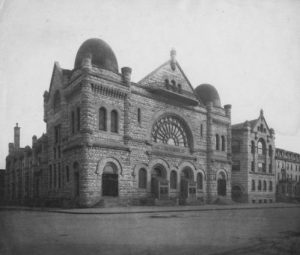

Shortly after Conwell and his family arrived, he and the congregation determined to build a larger building, and in a leap of faith, bought the land at the corner of Berks and Broad sts in 1886. Faith was also required to raise the funds to build the Temple. Groundbreaking took place in 1889, the building, an example of the Victorian Romanesque-revival style, was designed by architect Thomas P. Lonsdale, and Grace Baptist Church dedicated the building for worship on March 1, 1891.

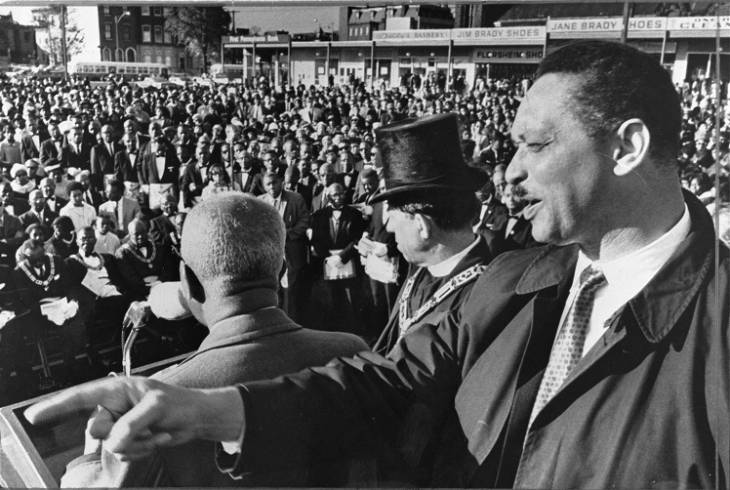

With a seating capacity of 4600, it was at the time one of the largest Protestant church buildings in the United States. The Temple served as the congregation’s home for the next eight decades, until they sold the building to Temple University in 1974 for a little over a half-million dollars. It hosted worship services, baptisms, weddings, funerals, Sunday School classes, community meals and events. At the same time, Temple celebrated scores of commencement ceremonies there–and Russell Conwell’s life at legacy during his funeral in 1925. The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., spoke at the Temple in 1965 in support of the desegregation of Girard College.

The building was certified by the Philadelphia Historical Commission as an historic building in 1984, and in 2003 it was designated by the American Institute of Architects as a Landmark Building. The University renovated the Temple to become its performing arts center, opening in 2010. Restored by the architectural firm RMJM in Philadelphia, it includes Lew Klein Hall, the main-stage space, in what had been the church sanctuary, featuring a thrust stage with seating for about 2,000 on three sides. Most of the building’s 140 stained-glass windows can be seen from the theater.

Sixty congregation members and friends visited Temple campus on May 1, 2022, to tour the Temple, visit Rev. Conwell’s grave, attend a reception and self-guided tour in Charles Library, and view an extensive pop-up exhibit featuring primary source material from the University Archives documenting Conwell’s life and the congregation’s early history. A selection from the exhibit remains on display in the Special Collections Research Center reading room through May.

Margery Sly, Director, Special Collections Research Center