Temple University Libraries mourns the loss of Thomas Whitehead, who worked for 45 years to grow the extraordinary archives and special collections held by the Libraries today.

Tom’s long and distinguished career in special collections librarianship began at Syracuse University, where he served in the Rare Book Department, first as cataloger and then as bibliographer. A native of Jamestown, New York, Tom received his BA from Bucknell University with a major in history and a minor in mathematics. He received his MLS from Syracuse University, where he also spent time as a lecturer in the School of Library Science, teaching a graduate course entitled “The Library and the Adult Reader.”

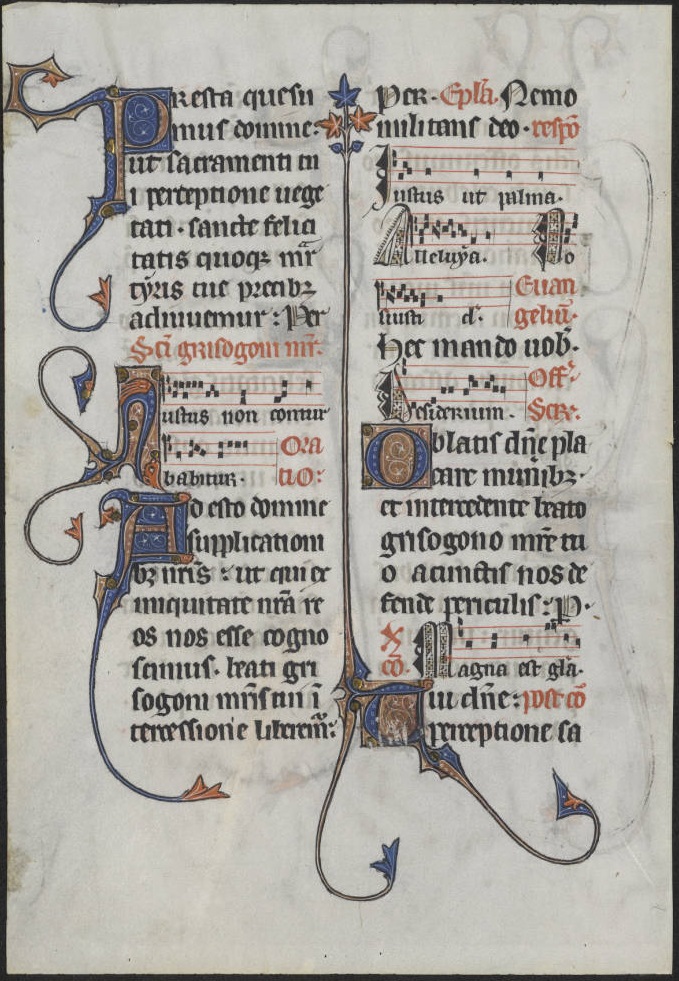

On August 14, 1967, little more than a year after Paley Library opened, Tom came to Temple as Rare Book Librarian. Through the years, Tom’s titles changed but his passion for rare books and manuscripts remained constant. Over the course of five decades, he acquired amazing additions to special collections, ranging from a stunning William Morris Kelmscott Chaucer, to illuminated manuscripts, to a wonderful Holinshed’s Chronicle. One of his final endeavors was completion of an extraordinary lithographic manual collection, including an 1818 edition of Aloys Senefelder’s classic work on lithography, considered one of the most important books published in the nineteenth century.

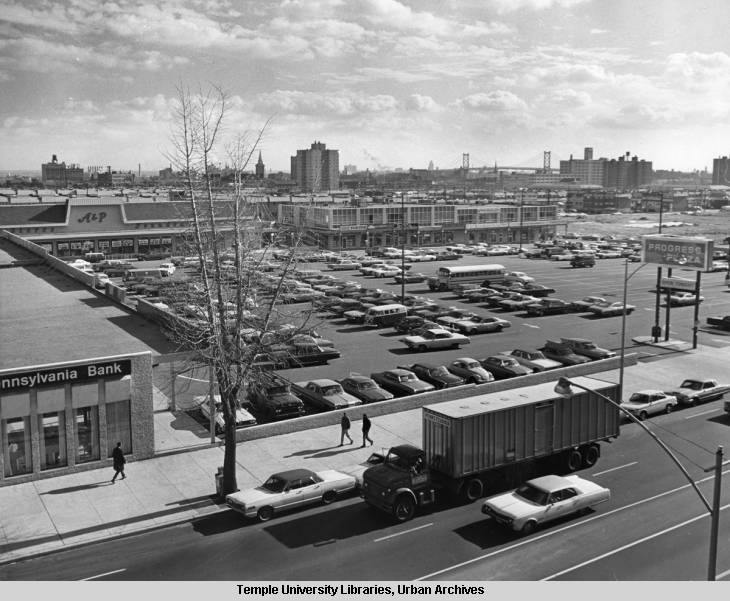

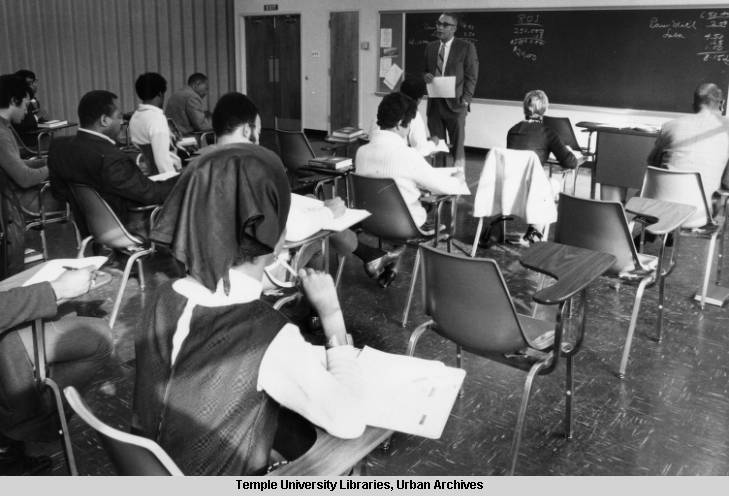

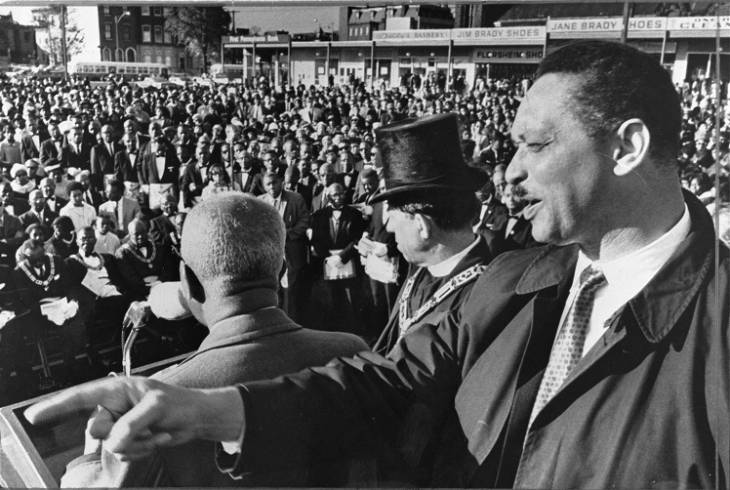

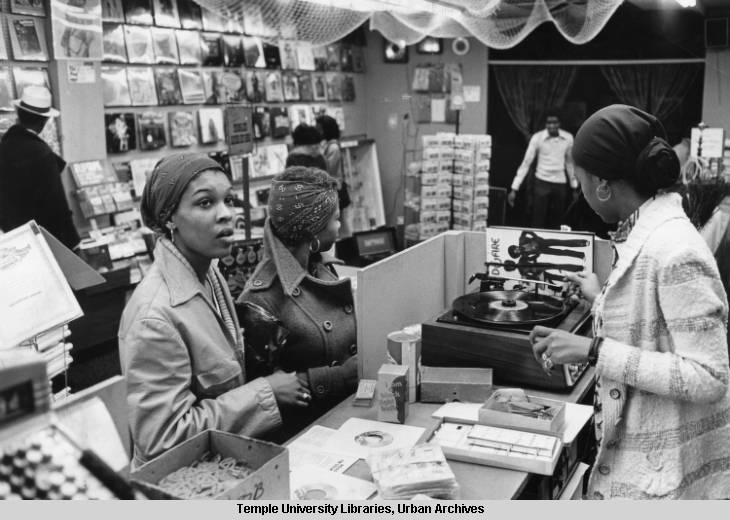

Tom brought many wonderful manuscript collections to Temple ranging from the literary papers of poet Lyn Lifshin, to the records of the Philadelphia Gay and Lesbian Task Force, to the papers of Father Paul Washington and the papers of Franklin Littell, a father of American Holocaust Studies. Other significant collections expanded by Tom include the Contemporary Culture Collection; the Science Fiction and Fantasy Collection; printing, publishing, and bookselling collections; and the list goes on and on. One of Tom’s lasting legacies is our Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection. Temple is the home of this incomparable resource documenting 20th century Philadelphia because of Tom’s single-handed efforts to save the material and house the archives here.

Starting in 1968, Tom was active in the Philobiblon Club of Philadelphia, serving as its secretary and on its board. As collector with wide reaching interests and a printer, “Amber Beetle Press,” he had a natural affinity with the Philobiblon members who are collectors, dealers, and curators.

Tom also served as Temple’s representative to the Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries (PACSCL) from the organization’s inception in 1985 until 2006. He retired as Senior Curator for Rare Books and Literary Manuscripts in January 2013. His retirement occasioned donations to the collections in his honor, and SCRC again plans to acquire an appropriate item dedicated to his memory.

Tom made an indelible impact on our special collections and the scholars and researchers who use them–a legacy that will continue to benefit future generations.

–Margery Sly, Director, Special Collections Research Center