Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is a teaching method commonly used in medicine and science curriculum, but it has also been applied in teaching history. (See Stallbaumer-Beishline, “Problem Based Learning in a History Classroom,” in Teaching History: A Journal of Methods, 2012.) Stephen Hausmann, an instructor in Temple’s History Department, contacted our Rebecca Lloyd, History’s library subject specialist, about using this approach for assignments in his General Education course, “Founding Philadelphia.” He hoped that this method of answering historical questions would increase student engagement and help them to develop information literacy and critical thinking skills. Rather than writing a research paper, the course was designed to have students working together in teams over the course of the semester to learn to think like historians and answer specific questions based on evidence drawn from primary sources.

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is a teaching method commonly used in medicine and science curriculum, but it has also been applied in teaching history. (See Stallbaumer-Beishline, “Problem Based Learning in a History Classroom,” in Teaching History: A Journal of Methods, 2012.) Stephen Hausmann, an instructor in Temple’s History Department, contacted our Rebecca Lloyd, History’s library subject specialist, about using this approach for assignments in his General Education course, “Founding Philadelphia.” He hoped that this method of answering historical questions would increase student engagement and help them to develop information literacy and critical thinking skills. Rather than writing a research paper, the course was designed to have students working together in teams over the course of the semester to learn to think like historians and answer specific questions based on evidence drawn from primary sources.

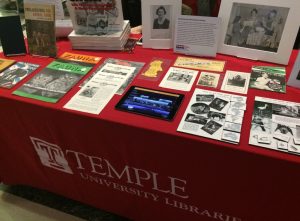

Librarian Rebecca Lloyd, held instruction sessions early in the semester to show students how to find and use the secondary and primary sources (drawn from her American history subject guide) that they would need to come up with answers to the PBL-based questions. She held follow up sessions to help with research and checked in throughout the semester to see how things were going.

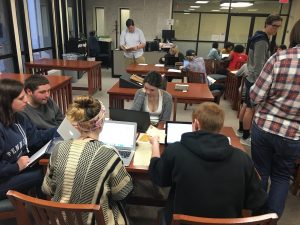

Using this same teaching approach the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) hosted a class session in our reading room. This was the last of the seven PBL-based assignments for the semester. Students were encouraged to handle and engage with the materials pulled for the class and use these primary sources to address two historical questions:

Using this same teaching approach the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) hosted a class session in our reading room. This was the last of the seven PBL-based assignments for the semester. Students were encouraged to handle and engage with the materials pulled for the class and use these primary sources to address two historical questions:

Question 1: The 1876 Philadelphia Exposition showcased the city as a modern, industrial, symbol of American strength and promise. This was very much in contrast with the dire economic situation the United States faced after the Panic of 1873. Look at some of the fair materials – in what ways did the Centennial Exposition foster this image? What attractions, items, displays, architecture, and landscape were used to create an American mythology at the event? Compare these with other collections from the 1870s. What contradictions do you see? In what ways was the exposition an accurate portrayal of late nineteenth century American life?

Question 2: One job of a historian is to piece together the basics of daily life in the past for different groups of people. Find two sets of documents that catalogue two different people from Philadelphia’s history. How were their economic and social situations different and similar? Describe their daily lives as best as you can and explain how they compared with one another. What did they eat and drink? What about their leisure activities or family life? What about the work they did or how they otherwise earned their pay?

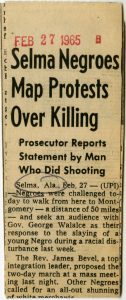

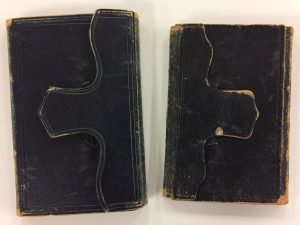

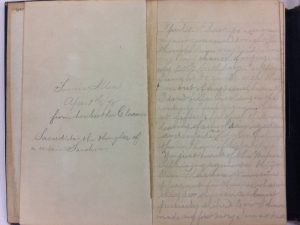

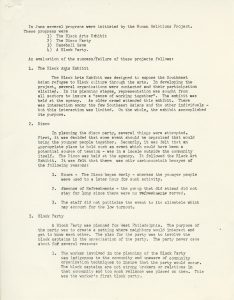

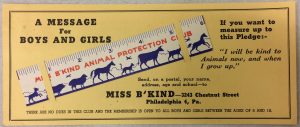

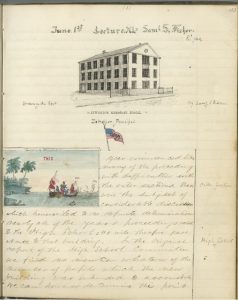

The SCRC materials used in this exercise were the Nathan S.C. Folwell Scrapbook, the George D. Shubert Diary, the Civil War Enlisted Slave Documents, the William Beatty Civil War Correspondence, Lectures on the Public Schools of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition Scrapbook, the History of the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children, and selections from the Young Men’s Christian Association Records, the Alliance Israelite Universelle, Philadelphia Branch Minute Books, and the William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Company Records.

At the end of the semester, Stephen Hausmann shared the following comments about his class’s experience in the SCRC working with primary sources:

“I had spent much of the semester training my students to use online databases. The visit to SCRC was a chance for them to use their skills in an “active” archival setting. One of my major objectives was to teach information literacy and ways of “reading into” a document, and I hoped that viewing archival material in the flesh would give students an opportunity to use those skills.”

Actively looking at documents in groups led his students “to draw many conclusions about the materials at hand in a way that never really happened during the usual, online, archival research sessions I held in class. Being able to walk around tables and pick up documents, turn pages, and discuss with their peers what they were seeing made for an archival experience I didn’t really foresee. in short, the visit’s collaborative nature achieved what I had been trying to get my students to understand all semester.”

“I think maybe faculty think a session like this will be extra work for them, while on the contrary it actually lessened my burden by allowing me to walk around and talk more with students substantially about the documents they were looking at. I couldn’t have been happier with how things went and some of my students told me it was their favorite single class of the semester.”

We intend to encourage instructors to try PBL-based assignments in their courses, as a hands-on alternative to the traditional research paper. The SCRC is uniquely suited to collaborate on just such an approach.

We intend to encourage instructors to try PBL-based assignments in their courses, as a hands-on alternative to the traditional research paper. The SCRC is uniquely suited to collaborate on just such an approach.

–Josue’ Hurtado, Coordinator of Public Services, SCRC