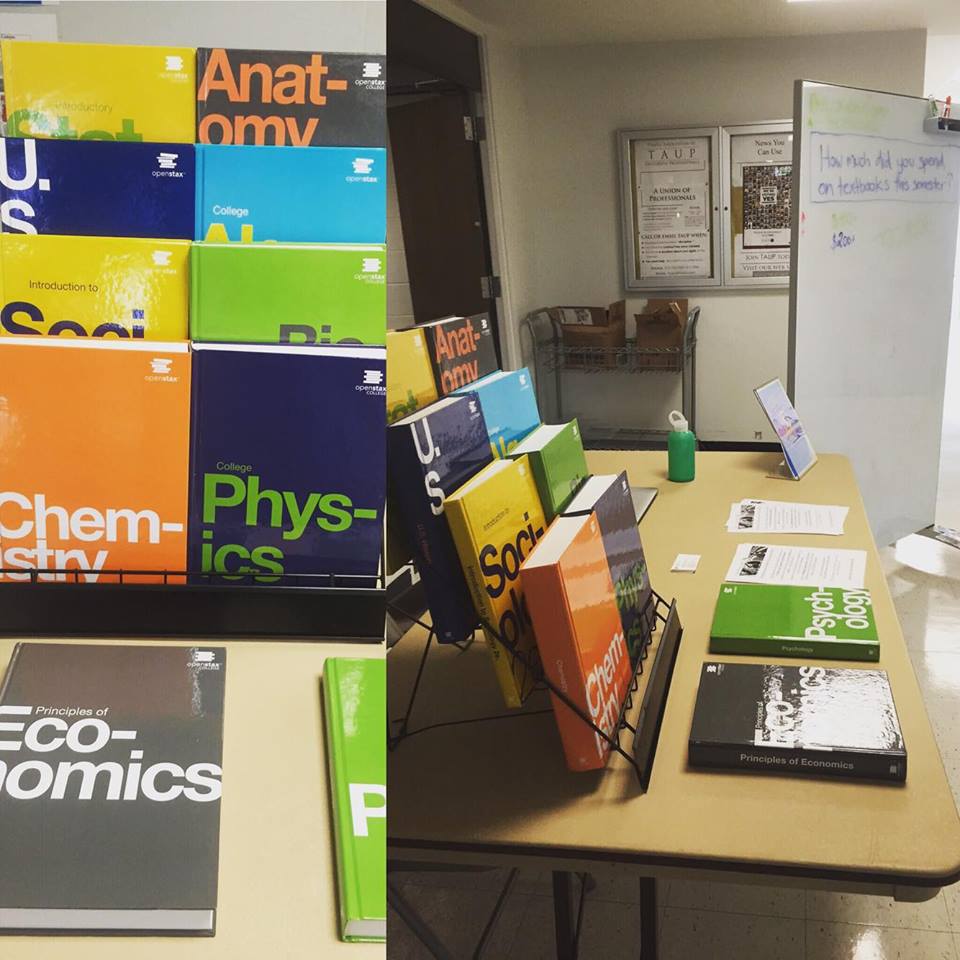

Image courtesy of Kaitlyn Mashack.

August 29th marked the beginning of the fall semester at Temple. As students started classes again, we thought it would be the perfect time to talk to them about affordable textbooks. So, we set up a table in the hall of Paley Library, and, armed with some flyers and our brightly-colored display of OpenStax textbooks, got to work. We thought we’d be doing most of the talking, but it turned out our students had a lot to say on this topic. Here are a few of their stories:

One student was very upset when she realized that her psychology textbook was going to cost her $200. She came to the Library to see if we had a copy, and was disappointed when she found out we didn’t have it (the Library has some textbooks in the collection, but doesn’t actively collect them). She told us she could rent a copy of the textbook for around $50, but before she does that she wants to keep trying to find a free copy. What’s the problem with this scenario? Well, while this student looks for a free or low-cost copy, she’s not actually doing the reading in the class. Instead, she’s falling further and further behind.

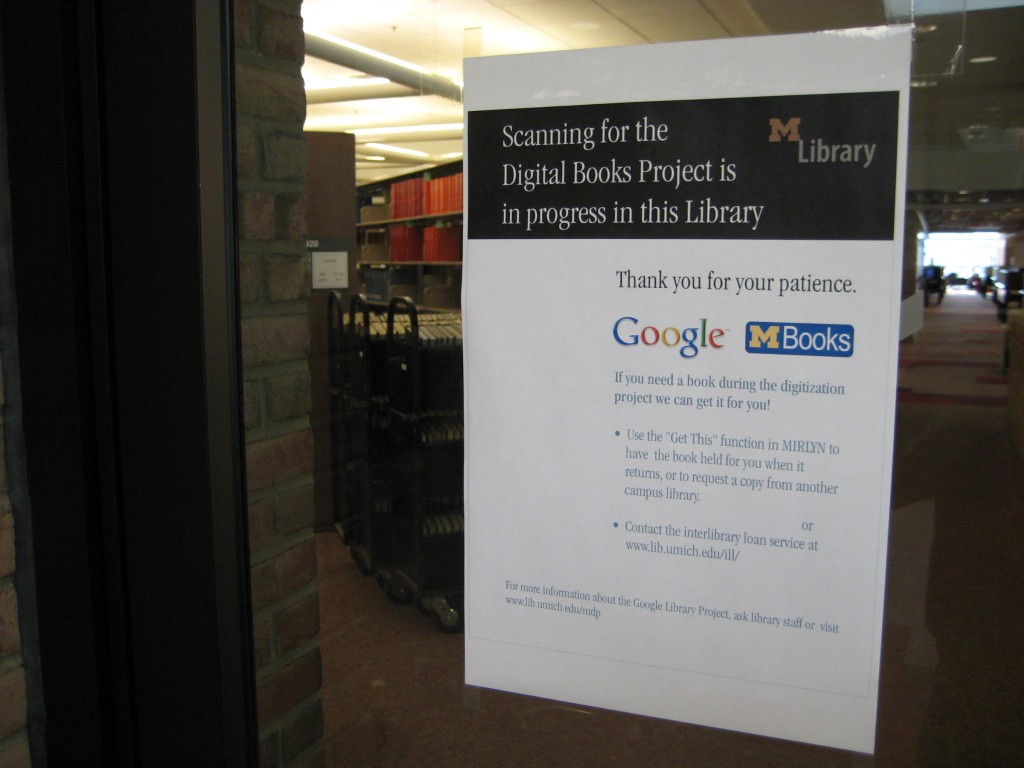

We also spoke with a biochemistry major who has never bought a textbook. He said he refuses to pay for textbooks because they’re too expensive and he just can’t afford them. He generally relies on Interlibrary Loan to get his textbooks. When it comes to lab manuals, he just photocopies them. He admitted that although this method has worked for him, it’s extremely time consuming. Wouldn’t it be great if instead of trying to track down free copies of his books every semester, he could spend that time studying?

Another student was in the Library looking for a copy of her $250 calculus textbook. Once again, the Library didn’t have it, and she wasn’t sure what to do. She did not have the money to purchase such an expensive book. We pointed her to the Open Textbook Library and found a couple of different options. She said she was going to ask her instructor if she could use one of the open textbooks instead.

To end on a positive note, we were excited to hear from a number of students who are taking a general chemistry class this semester from Professor Michael J. Zdilla. Zdilla assigns his students the Introductory Chemistry textbook from OpenStax. This textbook is available online, and is completely free for students to read, download, and print out. All the students we spoke with were thrilled that they didn’t have to pay for a similar commercial textbook.

Want to learn more about how the Library is supporting the use of affordable textbooks on Temple’s campus? Check out our Alternate Textbook Project.