In honor of Fair Use Week 2018, the following is a guest post from Digital Projects and Services Librarian Rachel Appel and Bibliographic Assistant III for Digital Projects Gabriel Galson. At the Libraries, Appel and Galson work on the PA Digital project. PA Digital is a statewide partnership that collects materials from Pennsylvania cultural heritage organizations and transmits them to the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA). The DPLA aggregates digital collections (images, photographs, text, maps, audio and video) shared by libraries and archives’ special collections all across the United States.

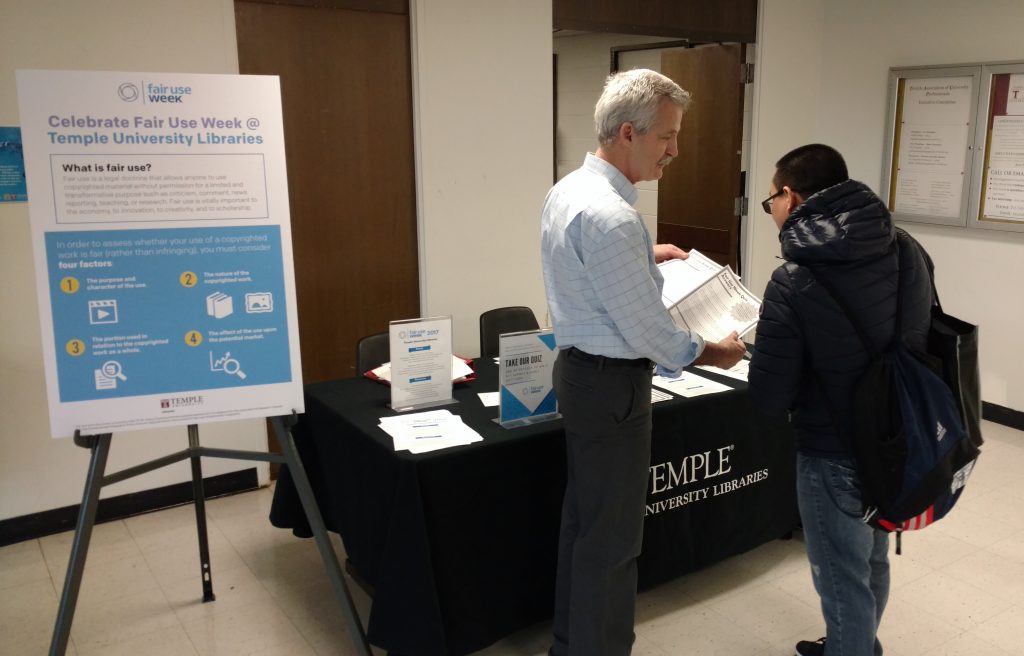

Fair use is a US legal doctrine that allows limited reuse of copyrighted materials. It is an invitation to the sort of intellectual/artistic exchange that keeps our culture vibrant, and a counterbalance against the the US’s increasingly strict copyright laws. Sampling, artistic appropriation, creative or educational quotation, parody, and text mining/textual analysis are all activities that flourish under fair use’s protection, shielded –to a degree at least– from the threat of litigation. Likewise, libraries, archives and museums around the country have been able to digitize their archival objects and make them freely accessible online because of the fair use doctrine. Many digital collections that are available through PA Digital and the Digital Public Library of America, for example, are in copyright; digitizing and making them publicly discoverable through a database platform is considered fair use. However, it is important to communicate clearly to users, such as scholars and researchers, that such works remain in copyright and have use restrictions and limitations. Fair use is a key concept that enables both digitization and reuse of digital facsimiles and is the rationale for making cultural heritage collections available online, in local repositories as well as the DPLA.

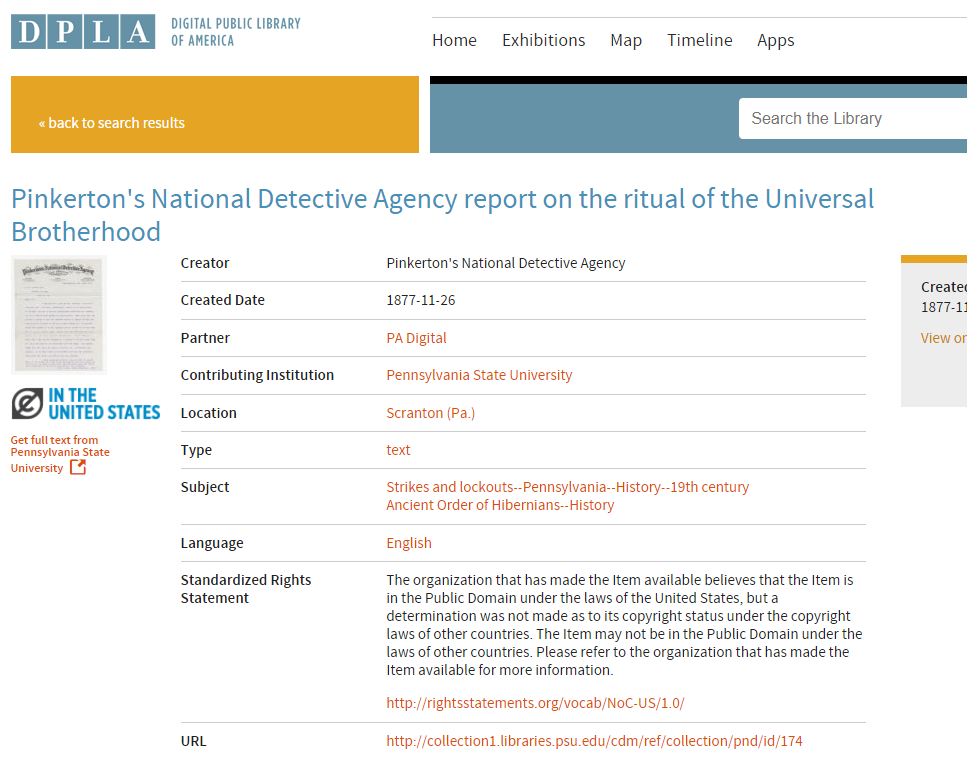

That’s where RightsStatements.org comes in. The site provides 12 normalized, standardized statements that cultural heritage institutions can use to describe the copyright status of online cultural heritage materials. A joint global project of Digital Public Library of America, Europeana, New York Public Library, University of Michigan, and other institutions, Rightsstatements.org went live in 2016. It creates three categories of statements (with four statements in each) to be used with cultural heritage materials, including some terms for use in the EU. The goal is to provide cultural heritage institutions with simple and standardized terms to summarize the copyright status of works in their collection and how those works may be used.

There are three overall categories with four specific rights statements within each: In Copyright, No Copyright, and Other. Rights Statements and Licenses are critical for digitization and data reuse. A normalized rights statement or Creative Commons license makes it so much easier for a member of the public to understand how that item can be used. The Digital Public Library of America has incorporated RightsStatements.org statements into their portal to function as a facet for searching because they are all machine readable and normalized. A similar metaphor is shopping through an online retailer – when we buy from online retailers what do we look for? Ideally, items with Free Shipping. This makes it easy for scholars to look for works that can be used in their publications and research.

Beyond traditional scholarship, normalized rights statements can also encourage creative reuse of works if people know what they can and can’t do. For example, DPLA’s annual GIF IT UP campaign, where users make images into gifs, and the #ColorOurCollections nationwide promotion by galleries, libraries, archives and museums, where end users are encouraged to reuse digital objects as coloring pages.

Rightsstatements.org is still getting off the ground, but it promises to make the process of identifying usable works far simpler and less time-consuming for researchers, scholars, and students. Take a look at the Europeana aggregator’s eight million plus ‘free reuse’ results for an example of what’s possible via machine-readable statements. Go forth and reuse!

More resources:

Ballinger, Linda, et al. “Providing Quality Rights Metadata for Digital Collections Through RightsStatements.org.” Pennsylvania Libraries: Research & Practice, vol. 5, no. 2, 2017, pp. 144–158. http://palrap.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/palrap/article/view/157

Fair Use Checklist: http://copyright.psu.edu/checklist/

RightsStatement.org Resources: http://rightsstatements.org/en/

PA Digital webinars:

- Copyright 101 video module

- “What is a Rights Statement?” video module

- “Implementing RightsStatements.org” video module

Menand, Louis. (2014). Crooner in Rights Spat. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/10/20/crooner-rights-spat