“Bike for a Better City”

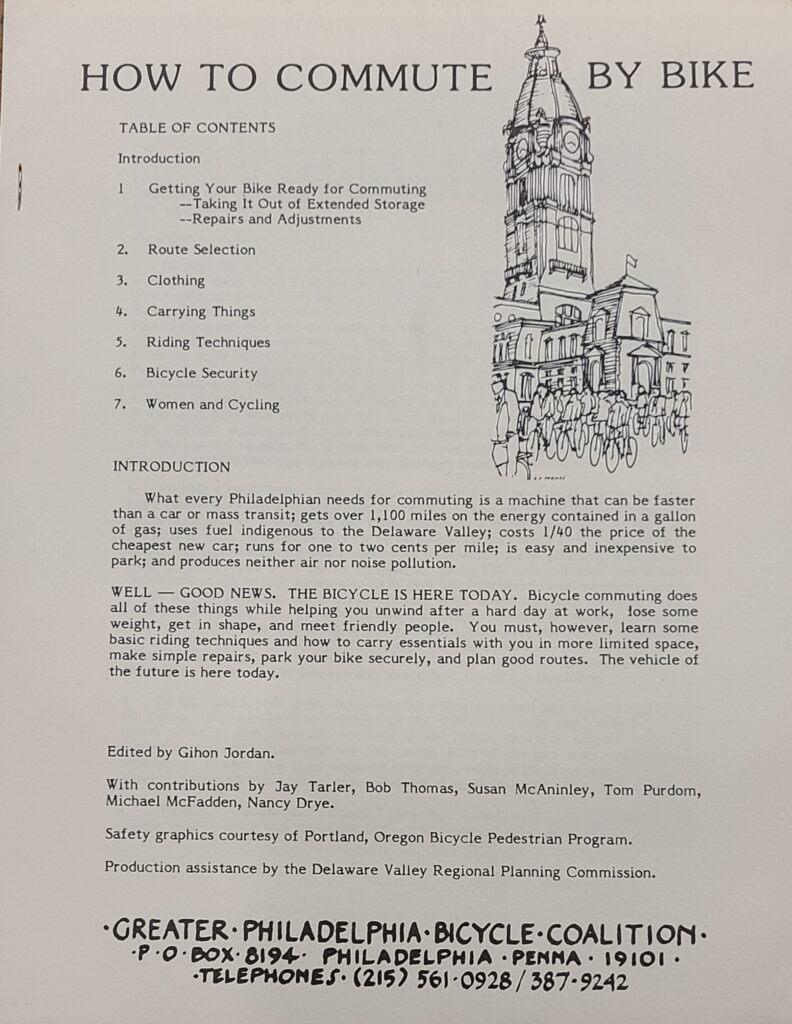

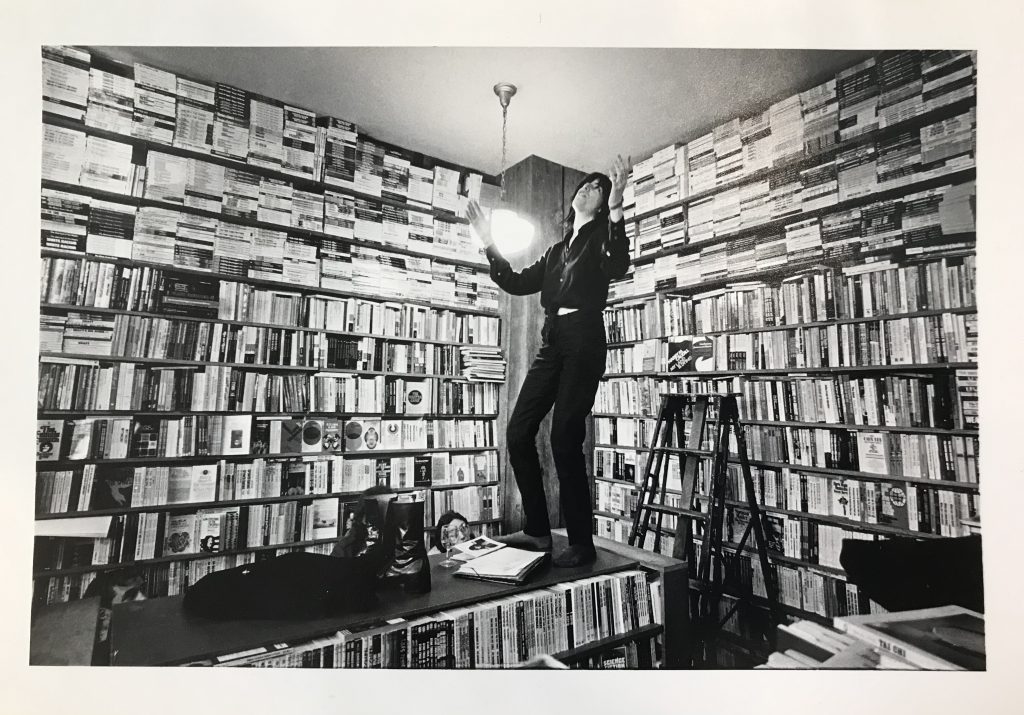

John Dowlin used the bicycle as a means of political, diplomatic, and environmental activism. In 1974, after recently relocating to Philadelphia, he co-founded the Greater Philadelphia Bicycle Coalition. Dowlin and the Coalition saw the bicycle as a viable, cheaper alternative to the car and the answer to environmental concerns, as well as traffic and congestion issues in the City. With a goal to increase bicycle ridership, they pushed for accommodations for bicycles on all public transit, including buses, trains and even planes, and safe bicycle lanes on city streets and even the Benjamin Franklin Bridge.

Dowlin was director of the Bicycle Parking Foundation, founder of the international Bicycle Network, and editor of Network News and the Cycle and Recycle reusable wall calendar. Internationally, Dowlin led Tour de Cana, bicycle touring in Cuba and Latin America, and was president of Citizen Diplomats, ‘people-to-people’ diplomacy in Cuba. In the 1980s, Dowlin participated in Bike for Peace, during which he and other bikers rode together from Leningrad to Washington, DC. He was also an active neighbor in West Philadelphia’s Powelton Village. Together with Drexel University and the Powelton Village Neighbors Association, he worked on the Westbank Greenway Project to improve the Schuylkill River banks in West Philadelphia.

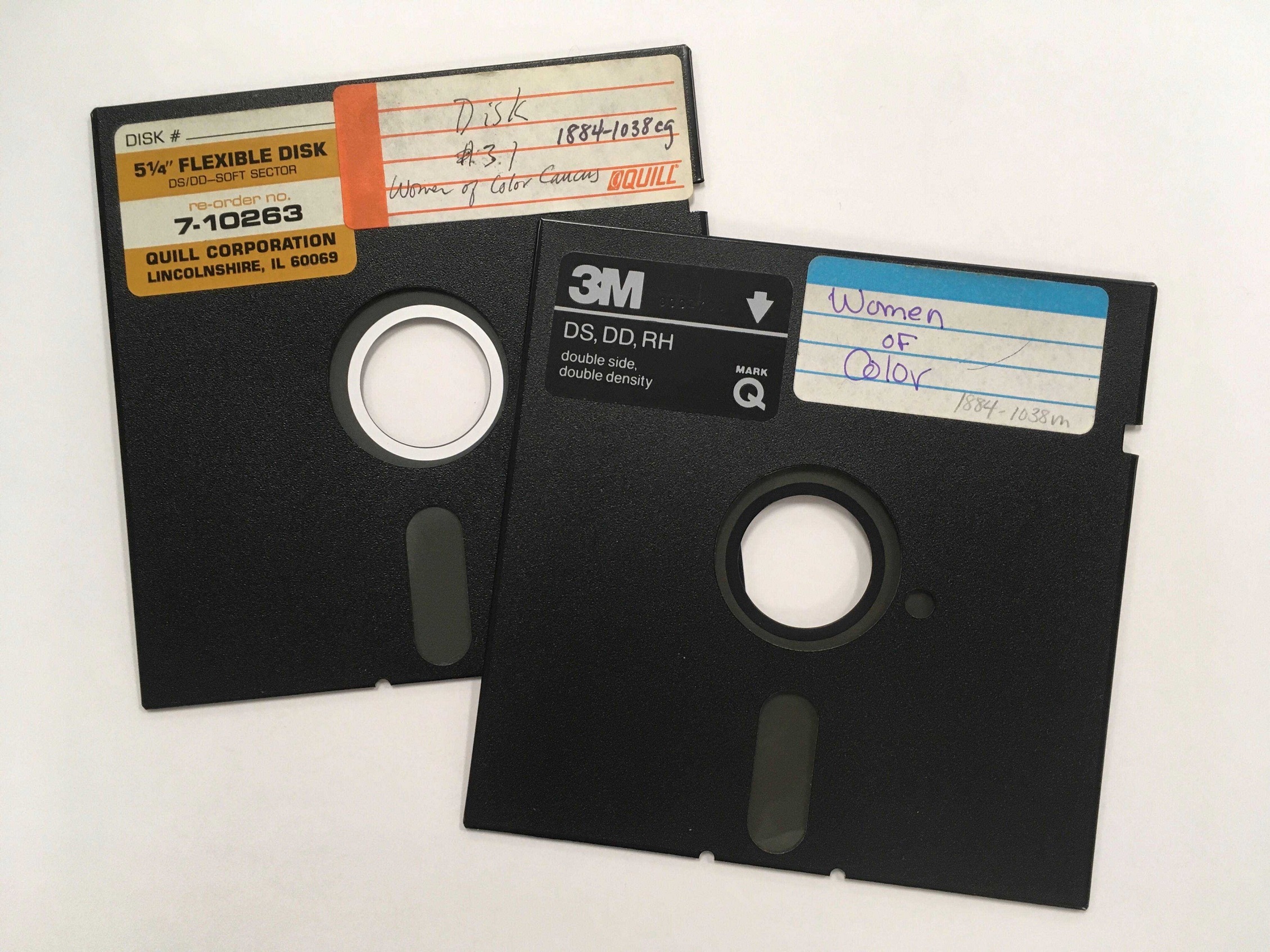

A small selection of John Dowlin’s papers documenting his work is on display in the Greenfield Special Collections Research Center Reading Room, Charles Library, for the month of December 2022.

Dowlin, with the assistance of his daughter Debby, donated his papers to the SCRC in Summer 2020. Staff are preparing the collection for research use. Among his many projects, Dowlin also worked with Rick Shnitzler on Taillight Diplomacy, promoting the preservation and restoration of Cuba’s old cars. Shnitzler’s papers, also in the SCRC, were recently opened to research use.

–Courtney Smerz, Collection Management Archivist, SCRC