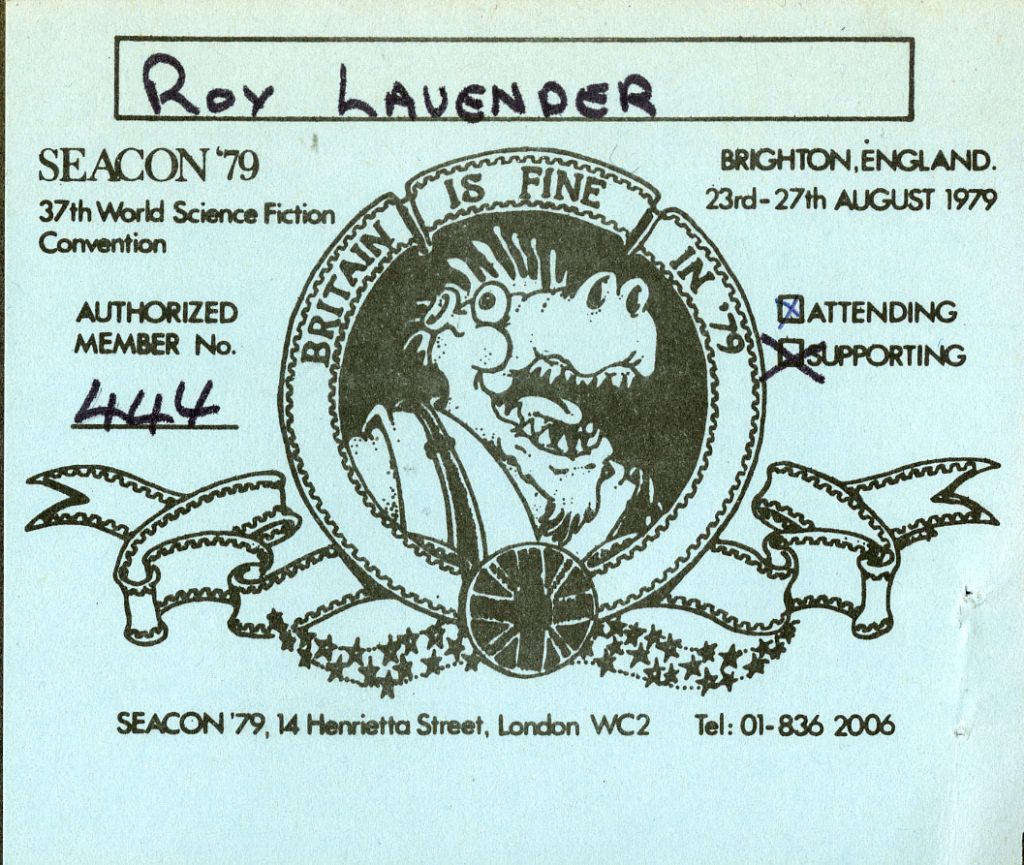

The Special Collections Research Center is fortunate to hold several collections related to the history of science fiction fandom. In addition to files of ephemera from science fiction conventions and three fanzine collections (the Science Fiction Fanzine Collection, Sue Frank Collection of Klingon and Star Trek Fanzines, and the Women Writers Fan Fiction Collection), we also hold the Carlos Roy Lavender Papers.

Roy Lavender was an aerospace engineer, science fiction fan, frequent convention attendee and organizer, and author of essays describing fan life in the early years of science fiction and the “pulp era.” Lavender was a member of First Fandom – an association of experienced science fiction fans originally limited to fans active prior to 1938 – and a founder of Midwestcon, a science fiction convention held annually in Ohio.

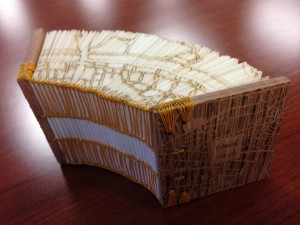

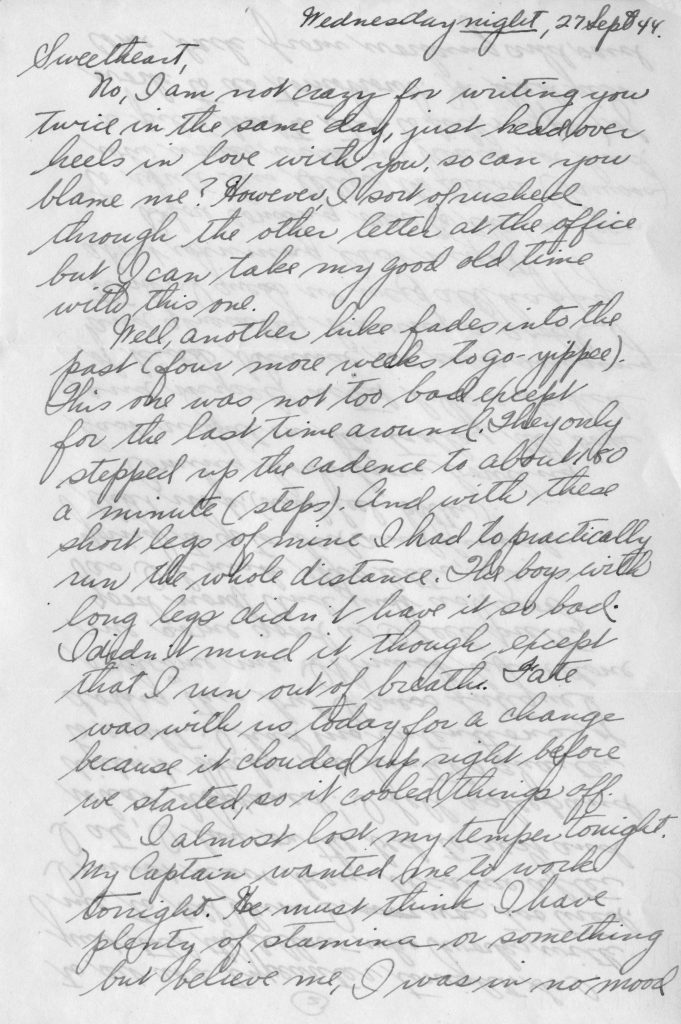

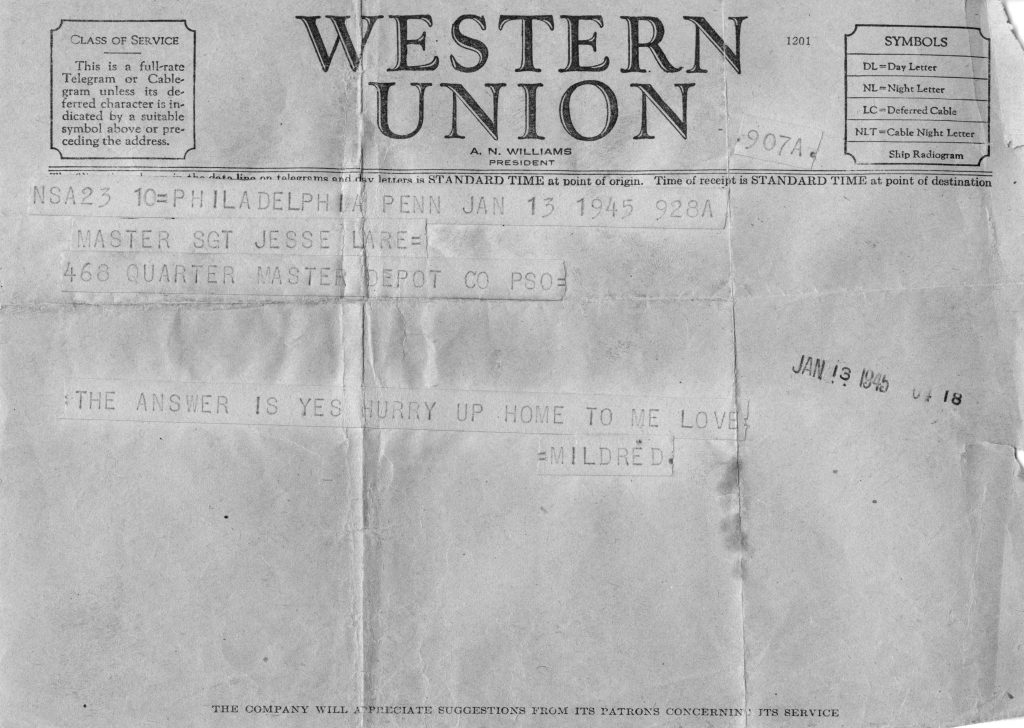

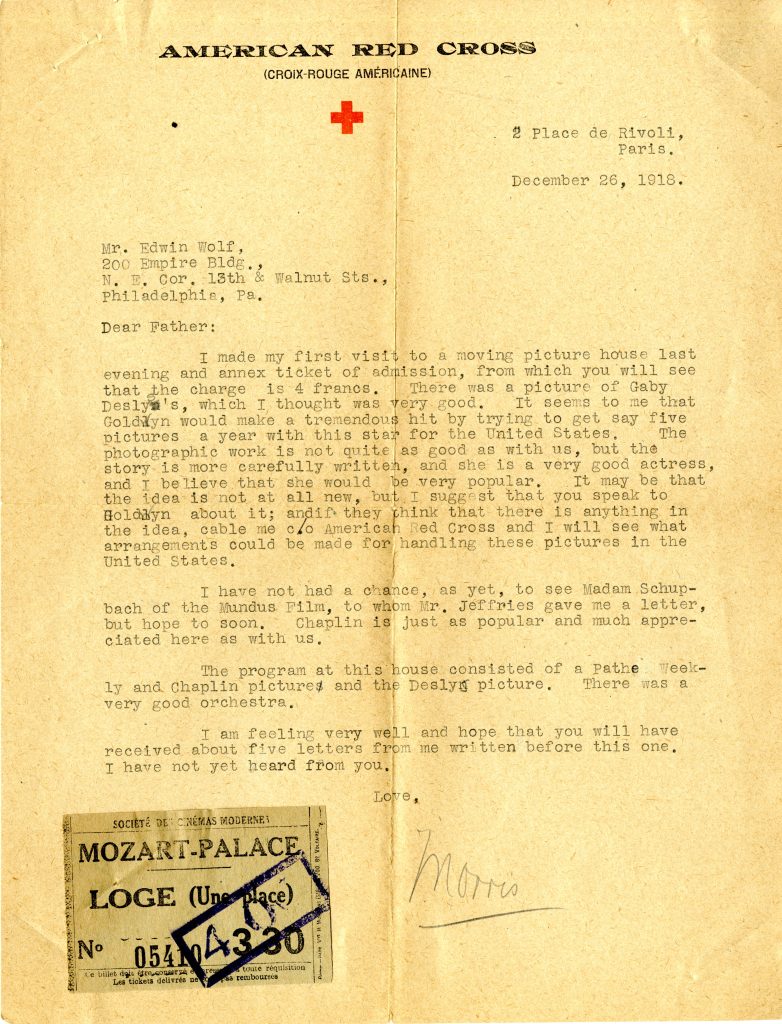

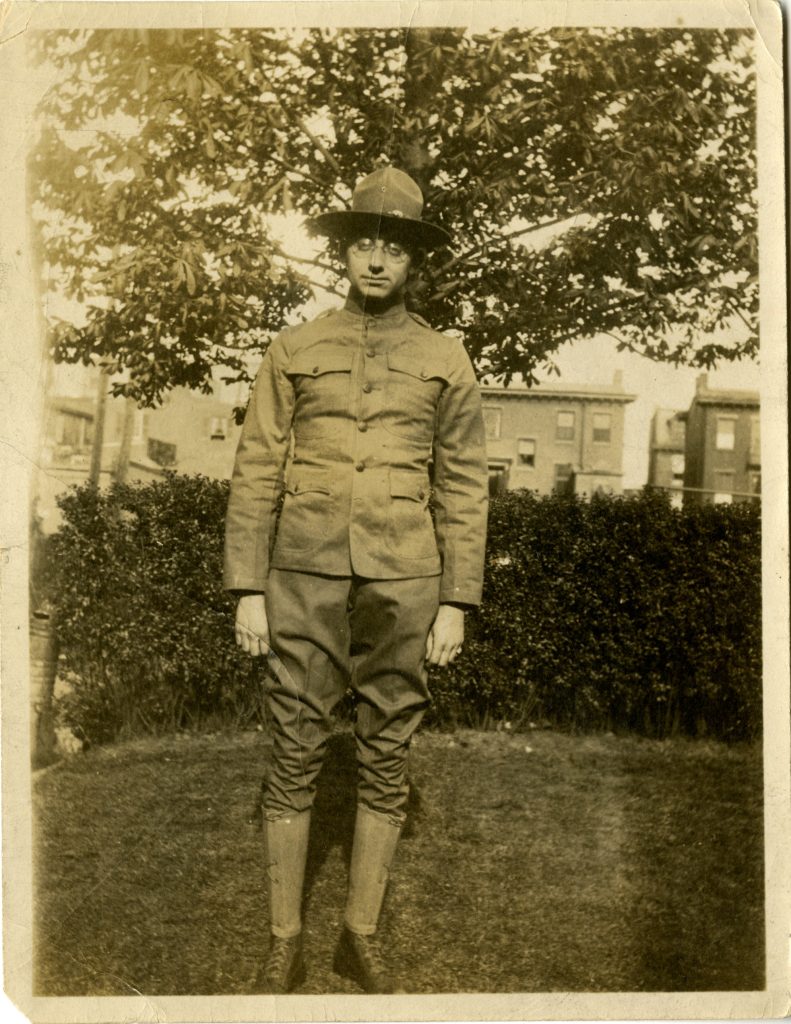

The Carlos Roy Lavender Papers include convention booklets and nametags, fanzines, letters, photographs, ephemera, newsletters, a scrapbook of science fiction writer Harlan Ellison’s column, “The Glass Teat: A Column of Opinion about Television,” and other materials. The many boxes of photographs and slides in this collection contain images of various science fiction conventions, including examples of cosplay.

While fans (of anything, but particularly science fiction) are often subject to ridicule, fan studies has grown in recent years. Fandom can be seen as a microcosm of the larger culture, and is intertwined with commerce, economics, entertainment, social connections and structures, and creativity. Documenting fandom has particular challenges for archivists. In addition to the scattered and ephemeral nature of much of what fandom produces, privacy concerns can also be an issue. Some fans do not want to be publicly associated with their fandom or the creative products they make, while others believe that the entire purpose of fandom creativity is to share what they produce with as wide an audience as possible.

A pressing current challenge for preserving fandom culture is capturing, preserving, and making accessible digital fandom: online zines, listservs, newsgroup posts, and blogs. These same challenges exist in many other types of contemporary archival collections, and archivists are increasingly well equipped through digital forensics, web archiving (for some of Temple’s contents, see our Archive-It site), and other measures, to provide the same care and access to digital materials as they have done with paper collections.

–Katy Rawdon, Coordinator of Technical Services, SCRC