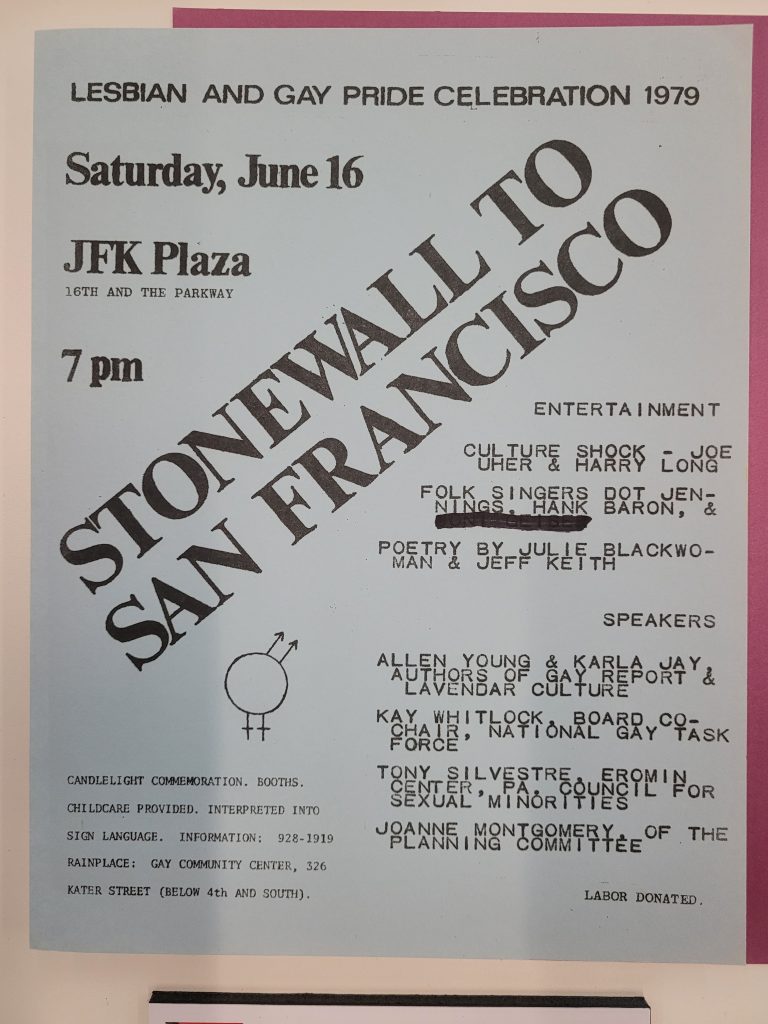

Pride month began in 1970 and is celebrated every June. It honors the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, when members of the LGBTQ+ community responded to a June 18, 1969, police raid at Stonewall Inn, a gay club in Greenwich Village, New York City, with a series of demonstrations. The demonstrations lasted six days, with many people arrested.

On June 28, 1970, the first Pride March occurred in New York City on the uprising’s one-year anniversary, with up to 5,000 marchers demonstrating against centuries of abuse and discrimination. Celebrations in the years afterward include parades, picnics, parties, concerts, workshops, and other events to recognize the impact LGBTQ+ individuals and organizations have had on history. Memorials are also held for those members of the community who have been lost to hate crimes or HIV/AIDS.

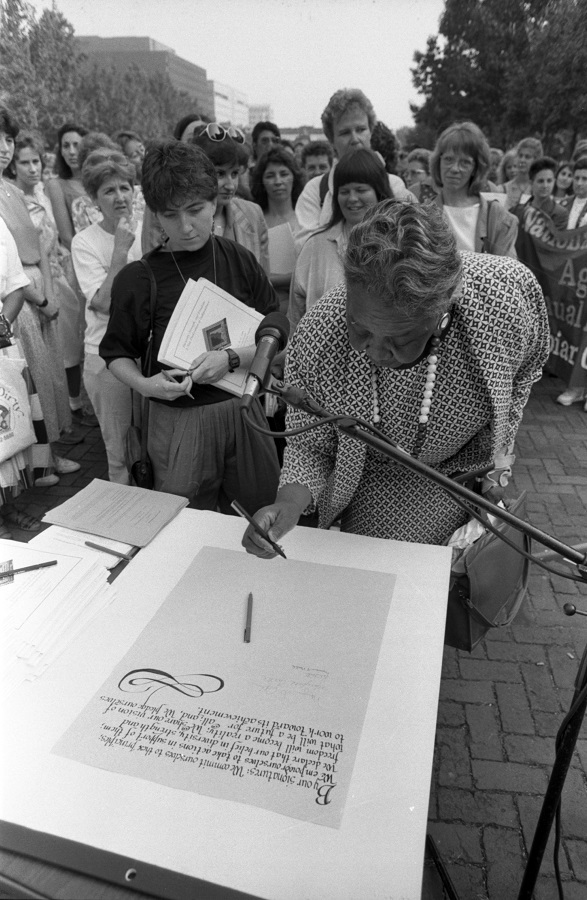

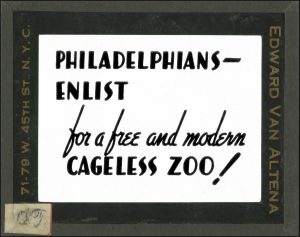

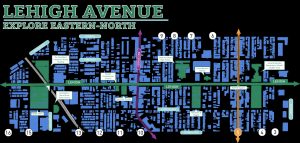

The first gay pride demonstration in Philadelphia took place on June 11, 1972, with over 10,000 people marching from Rittenhouse Square to Independence Park. While pride events took place every year, the parades would only continue for the next three years due to the more popular New York City parades. However, on June 18, 1989, the city resumed its gay pride parade and rally with over 1,000 people marching from 10th and Spruce Streets to JFK Plaza. The parades and rallies have continued in the city ever since. This year’s parade, scheduled for June 5, will look a little different, however, with a community march instead of a parade. It will be followed by a pride festival in the Gayborhood.

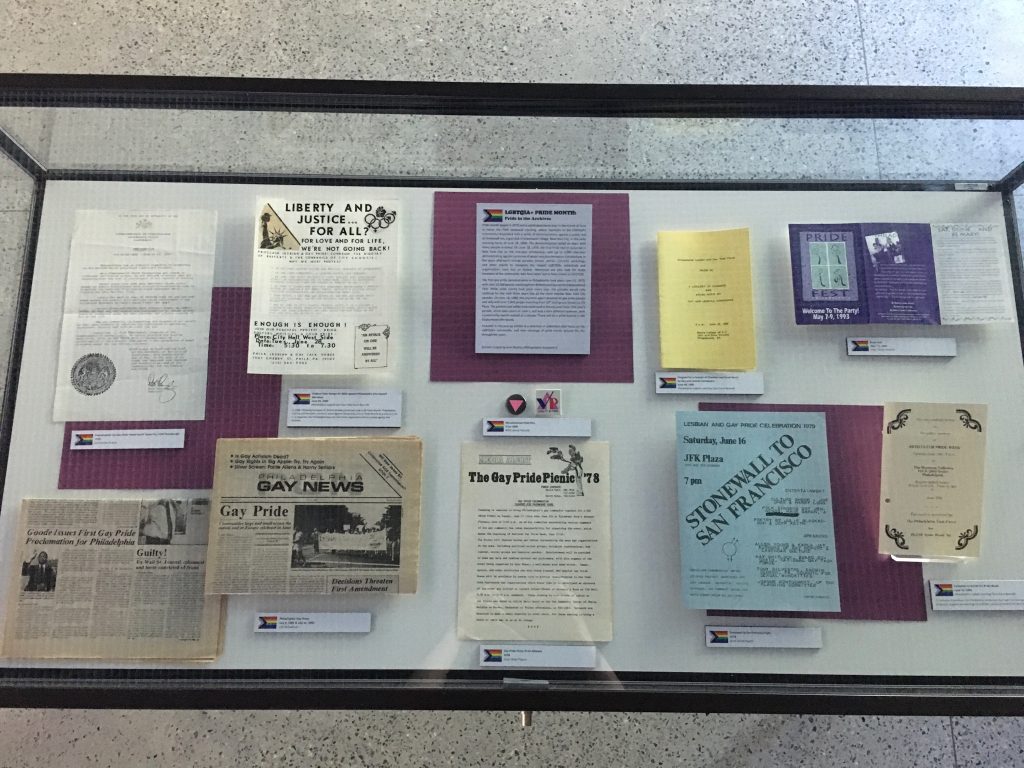

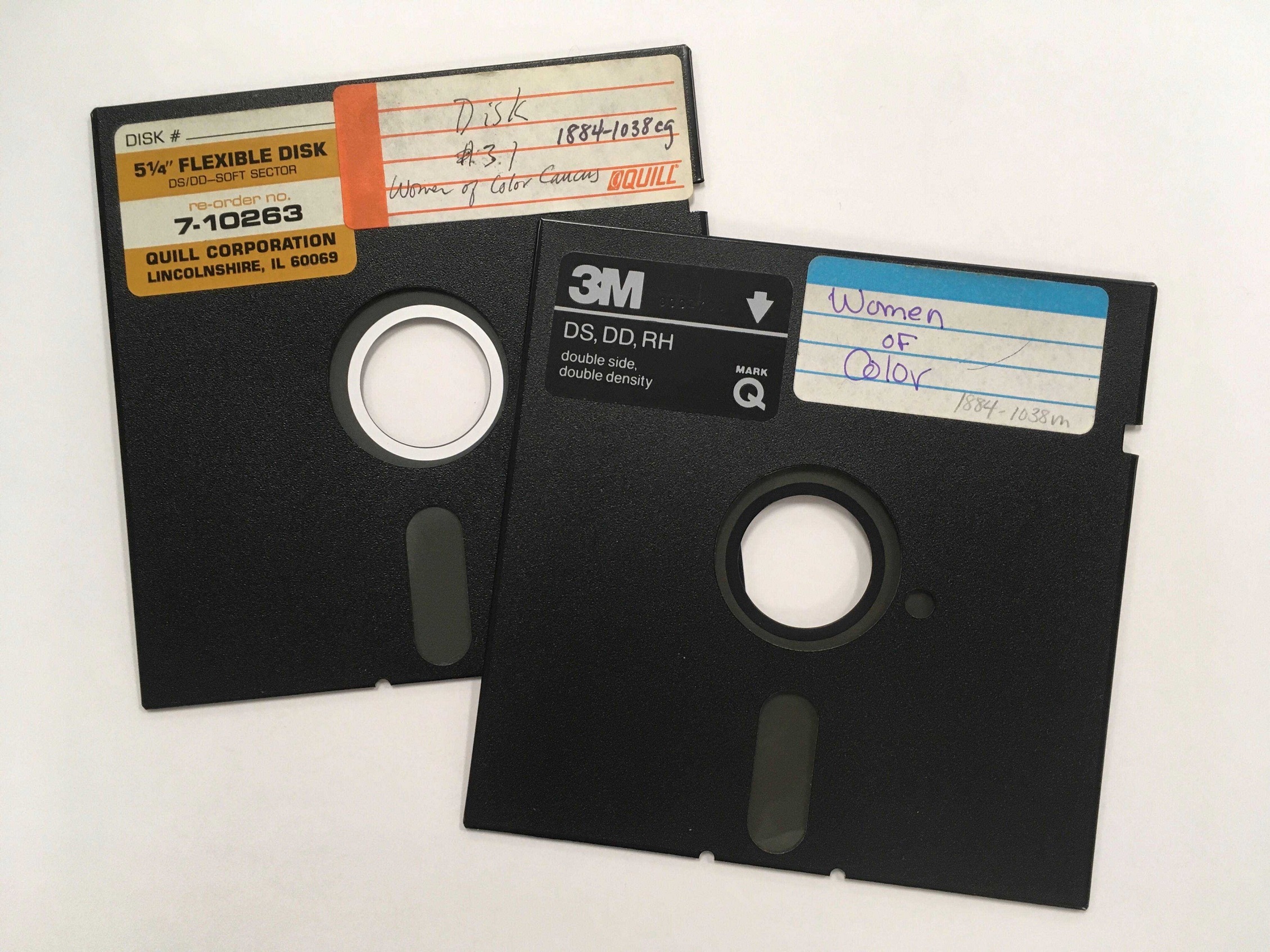

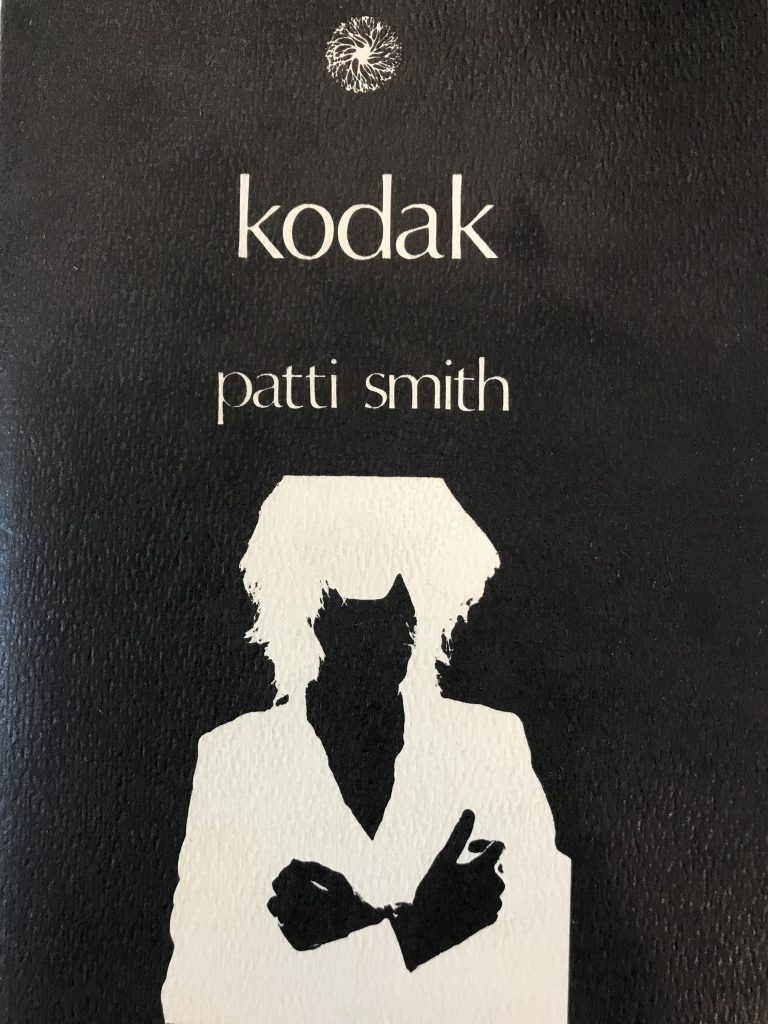

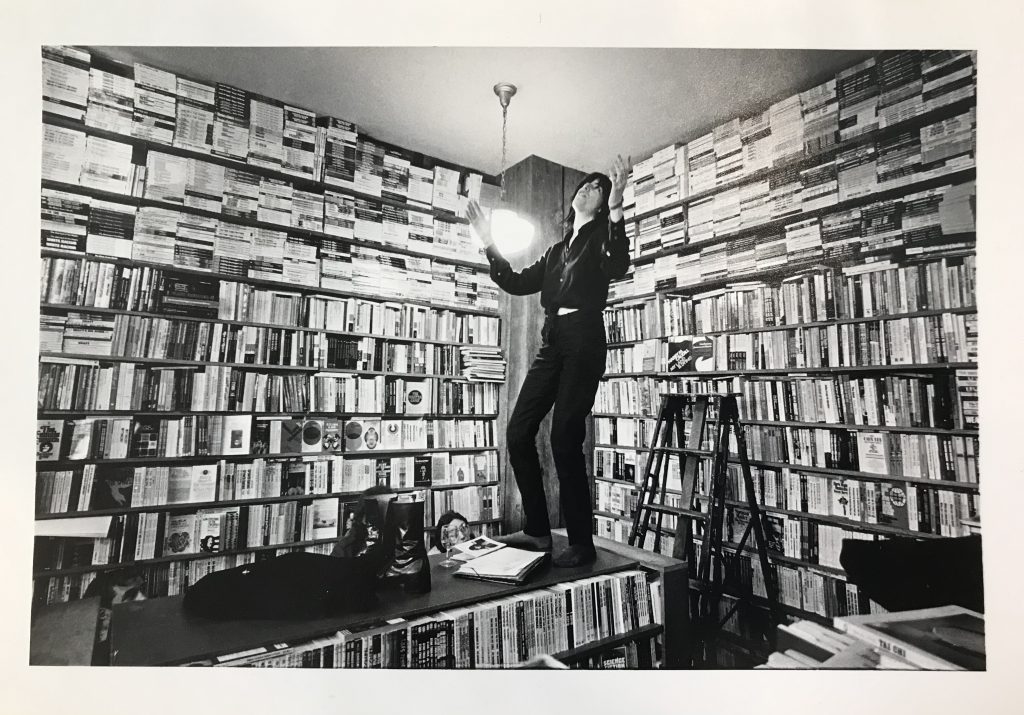

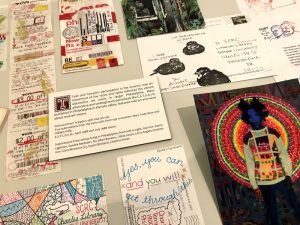

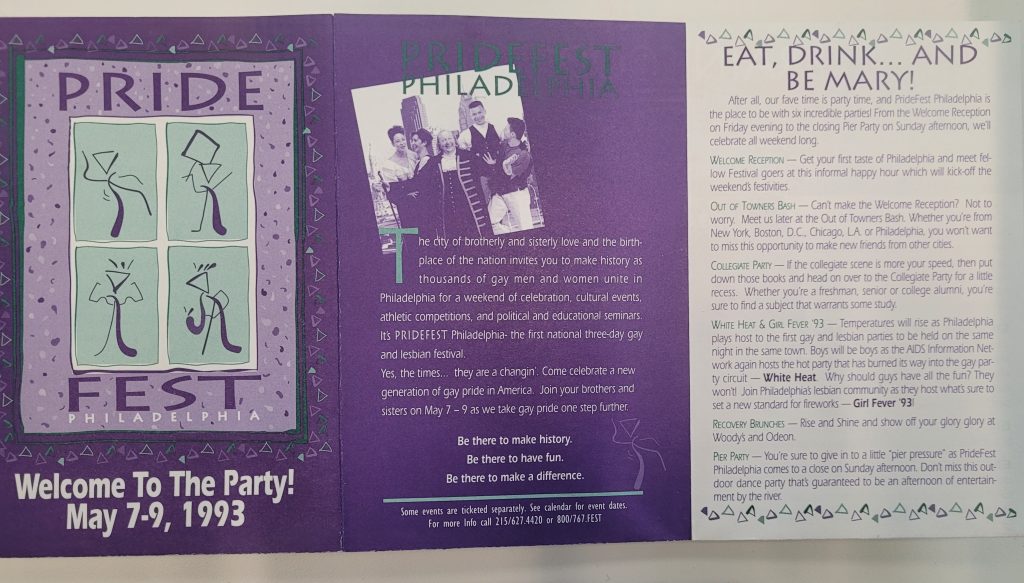

The Special Collections Research Center commemorates Gay Pride Month 2022 with a pop-up exhibit in our reading room featuring selections from collections that focus on the LGBTQ+ community and their coverage of pride events around the city through the years. The exhibit includes material from the AIDS Library (Philadelphia, Pa.) Records, the Philadelphia Lesbian and Gay Task Force Records, the Philadelphia Gay News, and the Scott Wilds Papers.

–Ann Mosher, BA II, Special Collections Research Center