Libraries and archives often maintain what they arcanely call “vertical files,” defined by Merriam-Webster as “a collection of articles (as pamphlets and clippings) that is maintained (as in a library) to answer brief questions or to provide points of information not easily located.” Other definitions note that the items in the file are too minor to require individual cataloging. And “vertical” refers to the actual storage orientation of the file folders—upright, often in a filing cabinet.

These files are simultaneously rich and idiosyncratic in content. A user never knows what might turn up and learns to enjoy the serendipity of finding a rich file, while being resigned to the disappointment of a skinny one.

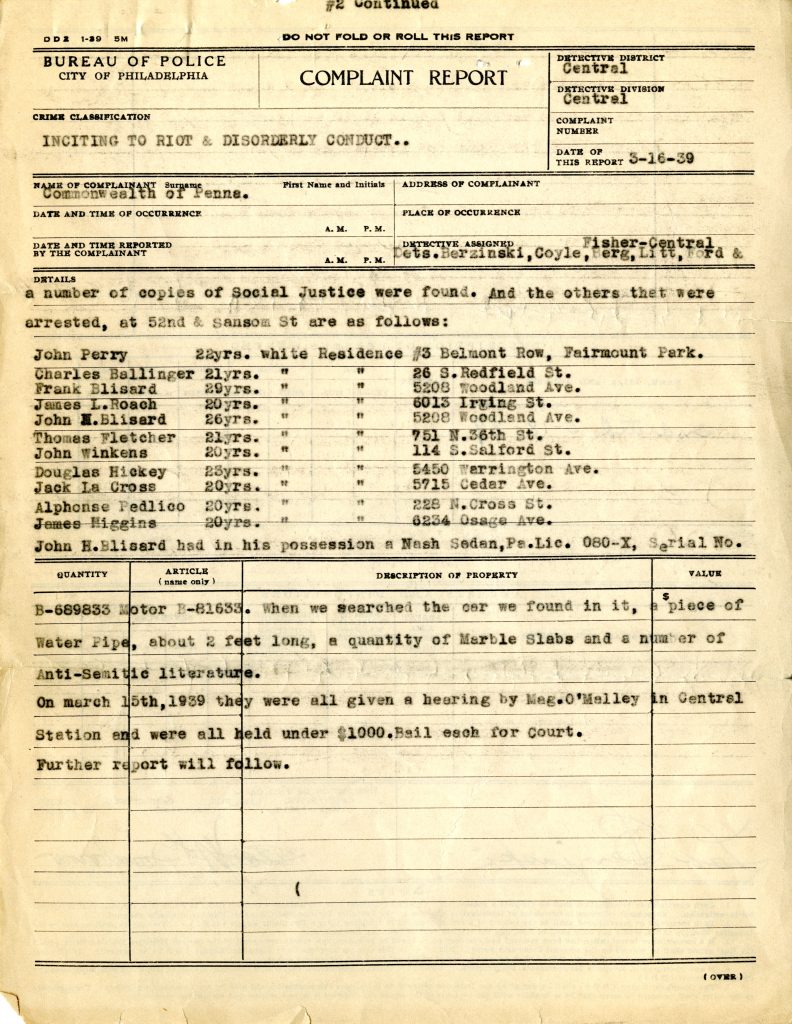

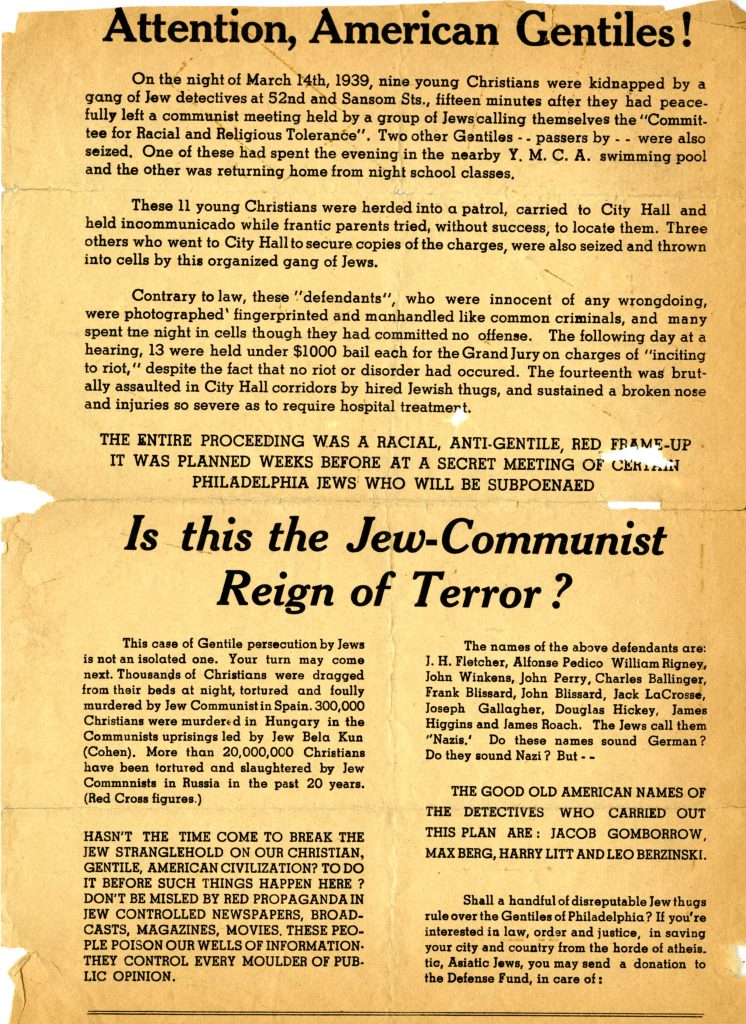

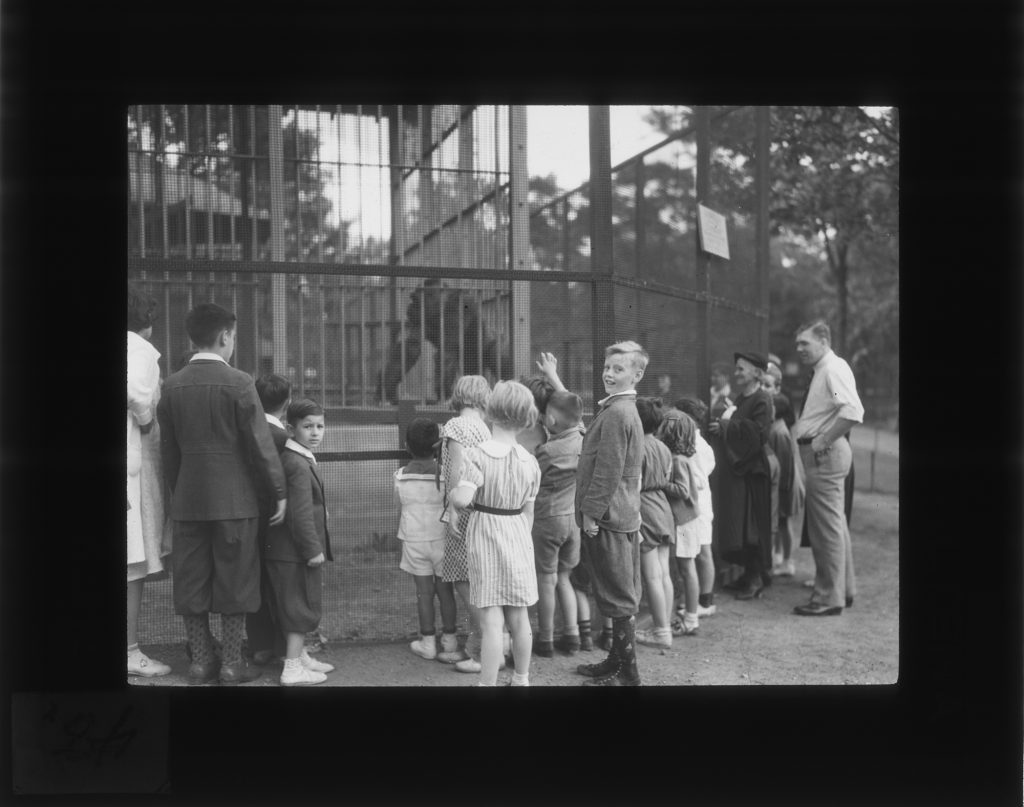

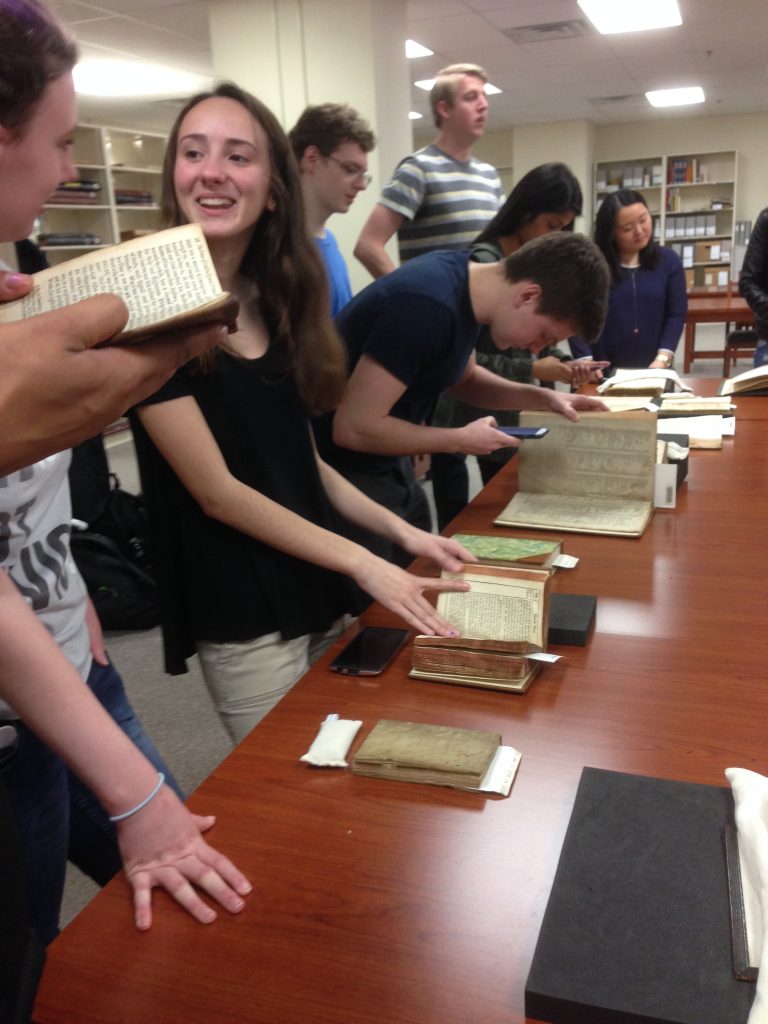

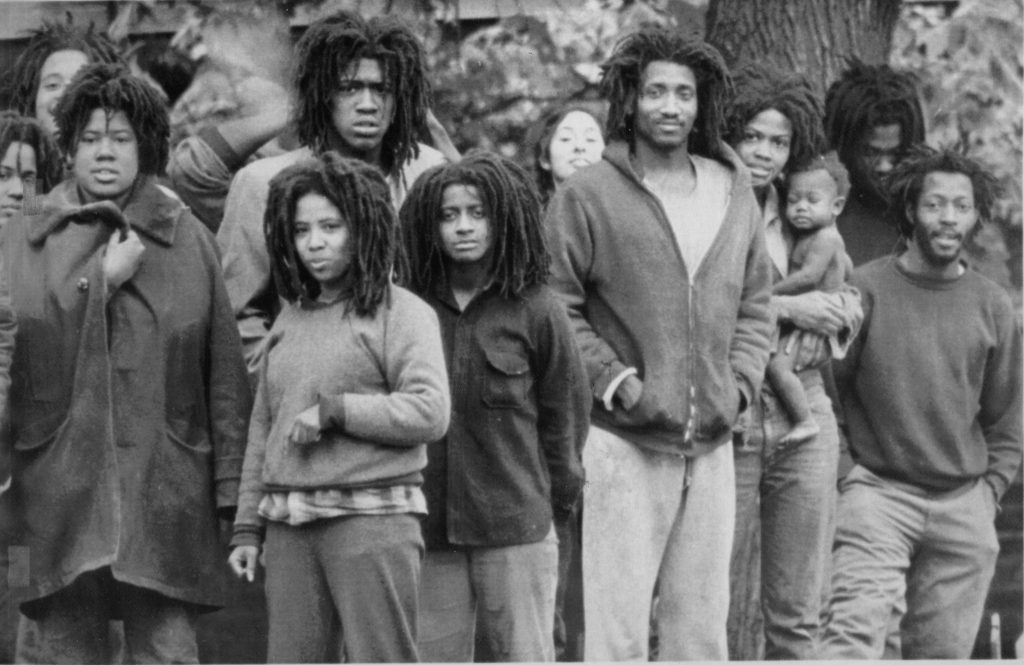

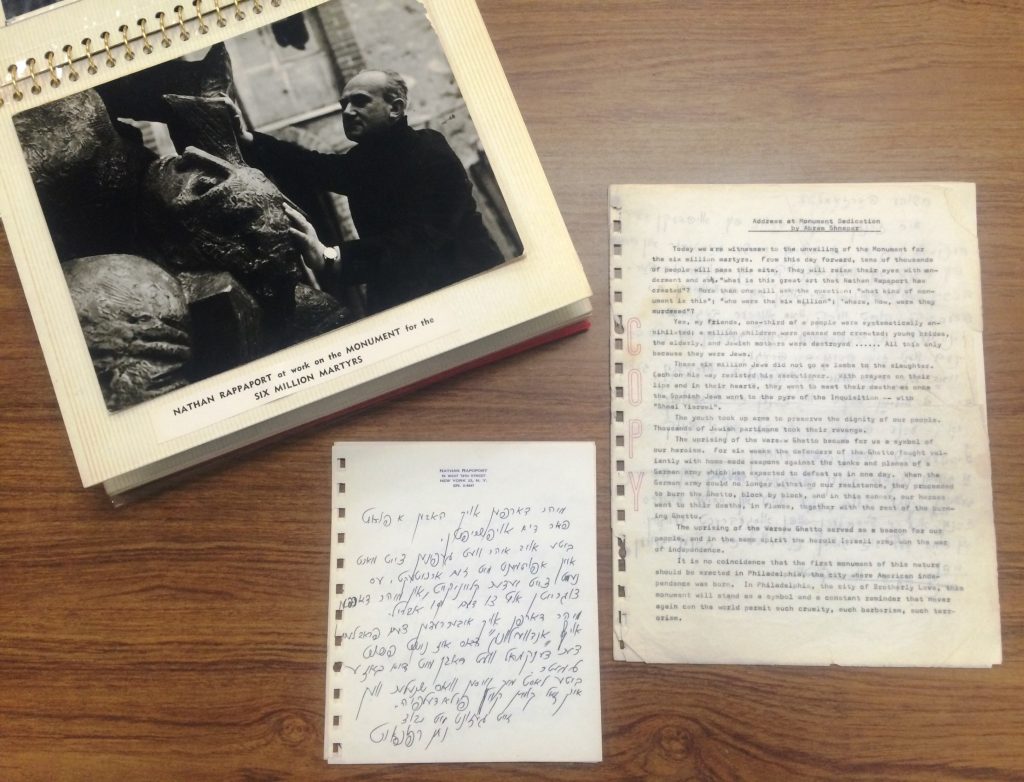

Temple University Libraries’ Special Collection Research Center maintains several such files. In the Philadelphia Jewish Archives, there are the Vertical Files on the Jewish Community of Greater Philadelphia which is an accumulation of items that document Jewish history in Philadelphia. The collection include photocopies of newspaper articles, pamphlets, family histories and genealogies, ephemeral items such as brochures, flyers and event programs and other miscellaneous materials relating to persons, places, organizations, and topical subjects. The files provide background information on cultural and historical events, businesses, and community members of the Jewish community in the Greater Philadelphia region and parts of southern New Jersey.

The inventory to the Temple University Archives Vertical File was recently put on line. It documents Temple’s founder Russell Conwell and many aspects of the University’s history. The collection contains publications, pamphlets, flyers and event programs, newspaper clippings, and other materials gathered from university offices and various news sources relating to persons, places, organizations, and topical subjects that document Temple University.

We’re reviewing the Science Fiction Collection Vertical File and the Dance Collection Vertical Files and hope to have information available about their contents soon.

Are these vertical files going the way of the dinosaur? At the moment, they are often superior to any search engine—or at least as good as the staff who faithfully gather and file the items—and serve as a great starting point and resource for many topics. Did you want to know about the Temple-Community Charrette of 1970; the model UN Conference that began at Temple in 1946; what Desmond Tutu said to the Temple community when he received an honorary degree in 1986? Start with the vertical file!

–Margery Sly, Director, SCRC