Photo by Alphacolor 13 on Unsplash.

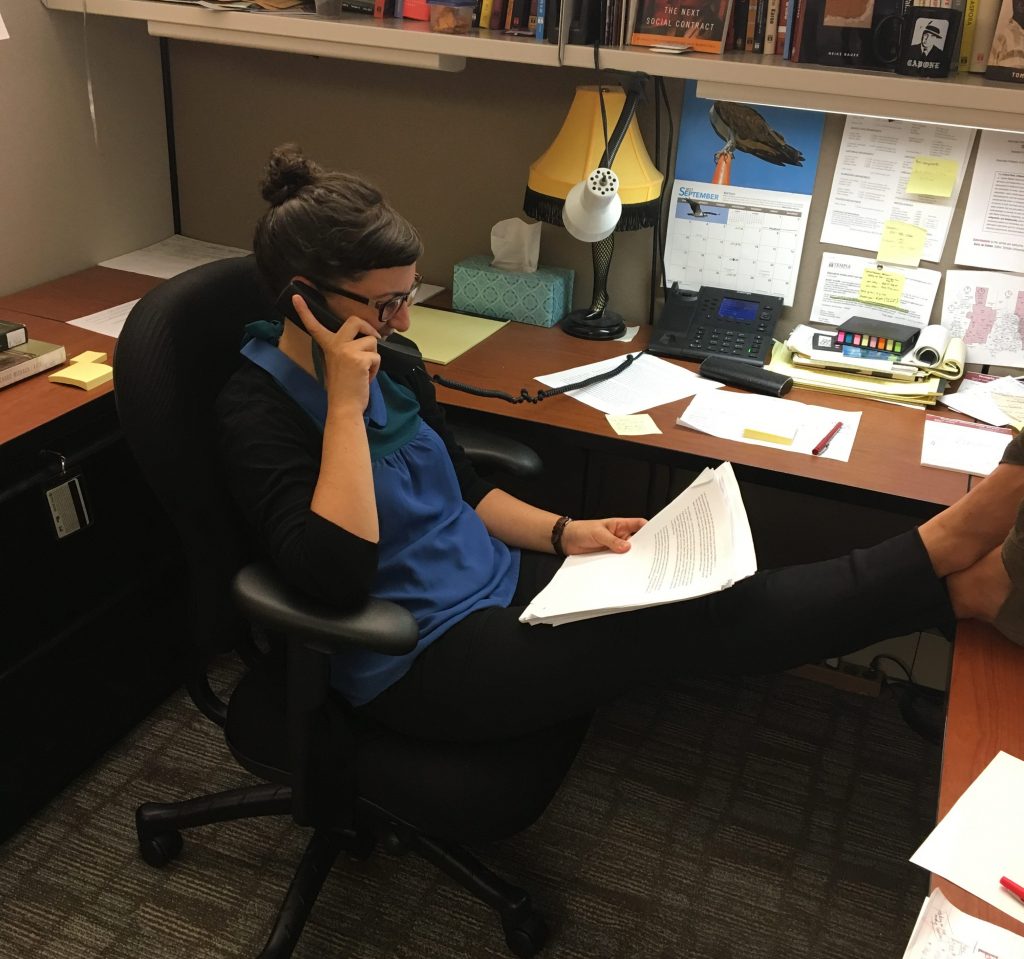

The following is a guest post by English and Communication Librarian Kristina De Voe.

Amid the amid the volume of news and information in today’s 24-hour news cycle, how can scholars, researchers, and academic leaders share their knowledge and expertise outside the classroom, laboratory, or institution? More importantly, how can they make that message relevant for a wider public audience?

On Tuesday, February 27, the Libraries hosted a panel of local experts who discussed podcasting as a viable way for scholars, researchers, and academic leaders to amplify and share their work with a wider audience.

The panel included Tom McAllister and Mike Ingram, both Associate Professors of Instruction in the English Department at Temple University and Hosts of Book Fight! podcast; Matt Wray, Associate Professor of Sociology at Temple University; and, Thea Chaloner, Associate Producer, Fresh Air with Terry Gross. Each panelist brought unique perspectives regarding starting, producing, promoting, and participating in podcasts.

With extensive experience in public radio, Thea Chaloner initiated the conversation by highlighting the popularity of podcasts: over 66 million people are listening to podcasts monthly. With over 250,000 podcasts out there, how does one start a (good) podcast, rising above the noise? Chaloner discussed two kinds of podcasts: the two-way (e.g. a relaxed interview or conversation between hosts and guests) and storytelling (e.g. RadioLab, This American Life), pointing out that the two-way is often logistically easier to create as the storytelling podcast usually incorporates background music, sound effects, and additional editing which can be time consuming.

Chaloner indicated that regardless of type, a good podcast needs thematic and narrative structure. Clear connections between episodes help as well as engaging questions that permit guests to paint a picture with words, inviting listeners to lean in to the story as they are washing dishes, commuting to work, or doing something else. The podcast can be niche in scope, too — this can, in fact, help to determine a loyal audience. Chaloner mentioned three free tools to help podcast creators: GarageBand and/or audacity for editing as well as Freesound for accompanying sound effects.

Mike Ingram and Tom McAllister then discussed their motives and considerations for starting their own podcast, Book Fight!. As both are creative writers, they desired to create the kind of program that they would want to listen to — something relaxed with writers bantering about books. While there was a learning curve for them early on, and a need to upgrade their equipment for better sound quality, Mike and Tom eventually found their groove, incorporating various themes (e.g. “Winter of Wayback”) and segments into each 50-70 minute episode.

Both Mike and Tom recognized the value of audience feedback along with building and interacting with their audience via outside channels like Twitter. They have also experimented with different funding models, including small crowdfunding campaigns and, more recently, using Patreon which lets listeners become members and give regular monthly contributions. Contributors then receive a bonus episode each month.

The final panelist, Matt Wray, offered strategies for academics who are podcast guests. Likening the experience to giving interviews to journalists and radio show hosts, Wray noted, however, that the best feature of podcasts is the conversational back and forth between host and guest, highlighting the seeming intimacy with listeners as they’re literally in their audience’s heads.

Wray stressed the importance of doing homework prior to being a guest on a podcast. He noted that, when contacted, potential guests should ask the producer and/or host what role they’re looking for in a guest (e.g. someone to explain, to persuade, to observe, etc.). Based on this information, the guest can let the producer and/or host know what they are comfortable sharing. Further, the guest should also ask for a list of topics and/or questions ahead of time to prepare, in addition to listening to earlier episodes of the podcast so as to get a feel for the program. Prior to the recording of the podcast, the guest should review relevant research — including their own — to avoid embarrassment and ensure that they can summarize key findings succinctly. Wray emphasized the importance of explaining concepts and ideas as if chatting with a neighbor or the dentist. He recommended that academics stick to 1-3 talking points, avoid jargon, and keep all responses short and to the point.

Thanks to everyone who came out to this informative program!