[ensemblevideo contentid=XzoRs8_9Pk-CekUYRe5niw audio=true showcaptions=true displayAnnotations=true displayattachments=true audioPreviewImage=true]

The early 2000s was an eventful period: a popping Internet bubble deflating the economy; the controversial presidential election hanging on chads in Florida and determined by Supreme Court justices long committed – at least rhetorically – to judicial restraint; the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington; and the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Polarized politics, contested economics, and lots of bombs dropping in faraway places.

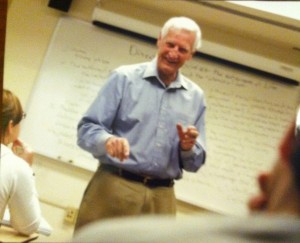

In these anxious times Professor Ralph Young created the Dissent in America course and students eagerly signed up. Young found students enthusiastic to learn about the history of dissenting voices and ideas in American history. Students were introduced to distant voices and gained insight on how the United States had come to its present circumstances. As an outgrowth of the course, Young started the Dissent in America Teach-Ins (see YouTube Video) on Friday afternoons which are open to anyone. Both the course and the teach-ins continue to this day.

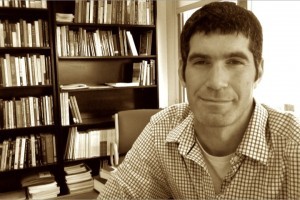

After Dissent in America became a General Education course, Young worked with librarian David Murray to add a formal information literacy component. Murray, an experienced instruction librarian, worked with Young for ten years before departing for the College of New Jersey in the summer of 2015. Young published two books as a result of his work on dissent: Dissent in America: The voices that shaped a nation and Dissent: The history of an American idea.

On December 2, 2015 I spoke to Ralph Young and David Murray on Dissent in America and their work together.