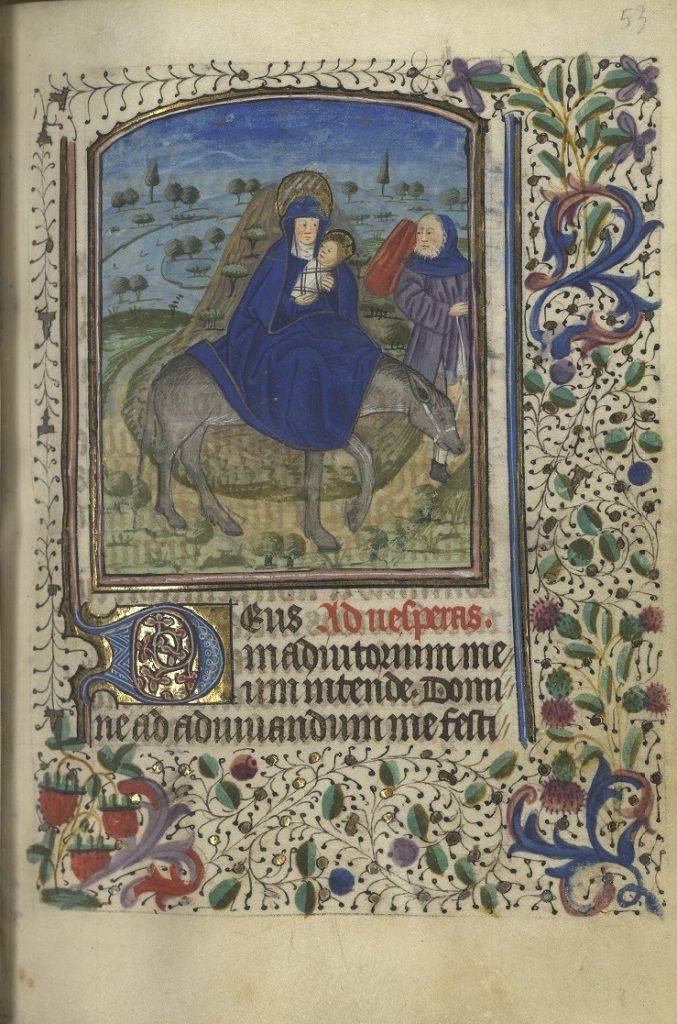

The Special Collections Research Center holds a number of medieval manuscripts of various types, including financial ledgers, notated music, a Book of Hours, and philosophical texts.

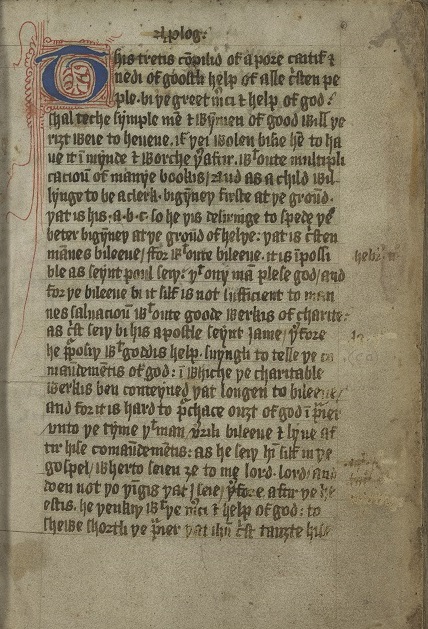

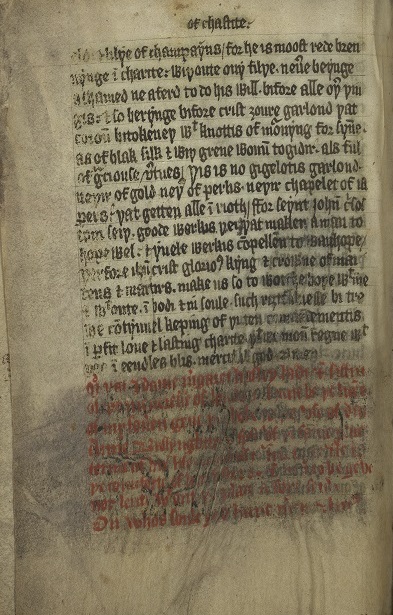

One interesting volume in the collection is a manuscript of the “Pore Caitif,” a late 14th and 15th century devotional text consisting of tracts intended for home use by the laity. The compilation of this handbook for religious instruction is most frequently attributed to English reformer John Wycliffe (1330 – 1384), and it contains approximately fourteen tracts intended to teach the reader about the Ten Commandments, the Paternoster, the Creed, and other basic aspects of Christianity. The number of Pore Caitif manuscripts in existence–more than fifty–demonstrates that this text was extremely popular during this time period.

It is unlikely that the compiler of this instructional volume was the one to assign the title “Pore Caitif,” even though that title seems to have been used as early as the 14th century. Most likely the common title was taken from the manner in which the compiler refers to himself: “pore” being an alternate spelling of “poor,” and “caitiff” or “caitif” meaning “wretched” or “despicable.”

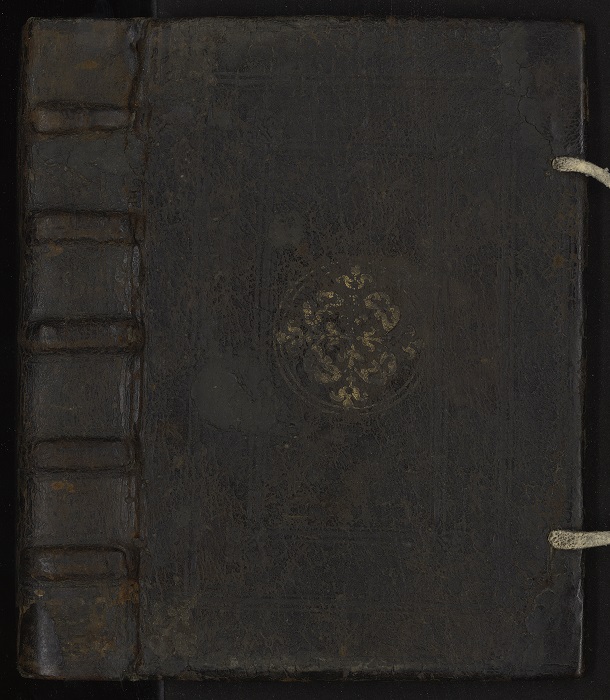

Temple’s Pore Caitif dates from the 14th century. It has a later binding from the 16th century, made of black Moroccan leather, and contains the bookplate of Robert R. Dearden, a 20th century Philadelphia book collector. An inscription on the last pages of the manuscript indicates that Dame Margaret Hasley, a sister in the Order of Minoresses, presented this work to another sister.

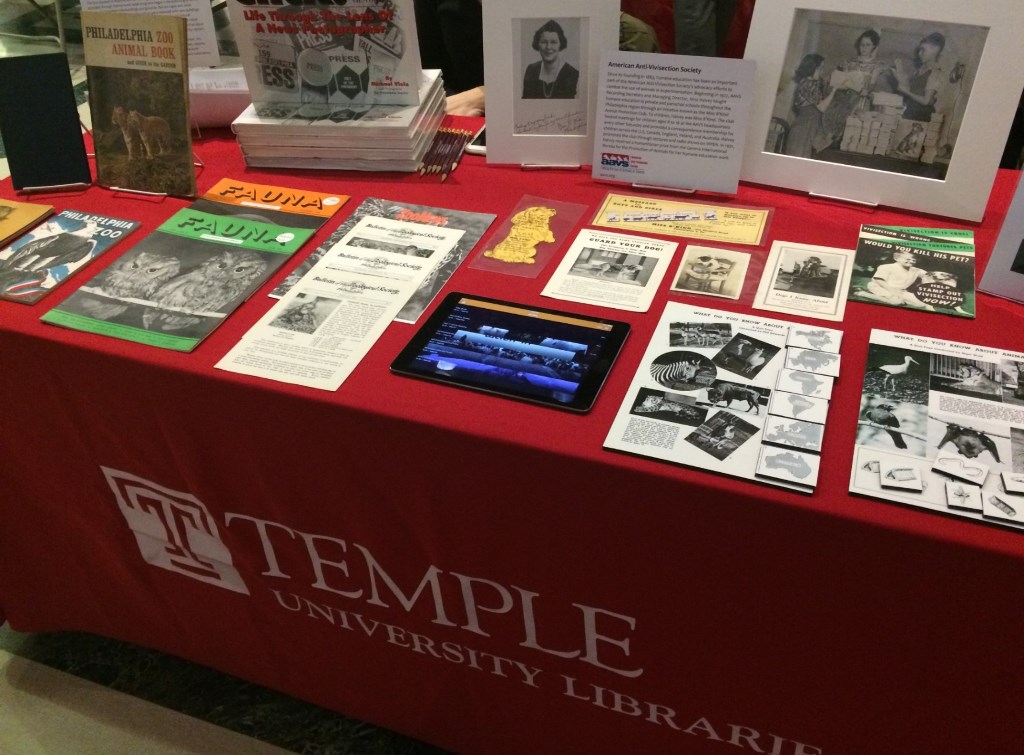

The volume was recently digitized for the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis project, funded by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) and sponsored by the Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries (PACSCL). The project aims to digitize and make available online medieval manuscripts from fifteen institutions in the Philadelphia area. Images and descriptive metadata will be released into the public domain and easily downloadable at high resolution via University of Pennsylvania Libraries’ OPenn manuscript portal. Temple is contributing over twenty manuscripts to the project.

–Katy Rawdon, Coordinator of Technical Services, SCRC