On January 7th and 8th, instructors from Temple and several other nearby schools braved the winter weather, gathering at the Howard Gittis Student Center to attend the 24th Annual Faculty Conference on Teaching Excellence (AFC). Our theme this year was Keeping the Promise: Building Academic Bridges to Support Student Success.

Our keynote speaker was Dr. Josh Eyler, Senior Director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching & Learning and Assistant Professor of Teacher Education at the University of Mississippi.

Dr. Eyler is author of a number of books on teaching and learning, including How Humans Learn: The Science and Stories behind Effective College Teaching, which was named one of the “100 Best Education Books of All Time.” In his address, titled Ariadne’s Thread: Finding Our Way Through Challenging Times by Focusing on Human-Centered Learning, he outlined the five aspects instructors need to attend to in their students to foster more effective learning: curiosity, sociality, emotion, authenticity, and failure.

Dr. Eyler’s message was supported by a series of faculty-led workshops, including one facilitated by Dr. Nyron Crawford of Temple’s Department of Political Science. Dr. Crawford’s workshop was called “Authentic Learning: The Curious Case of You.”

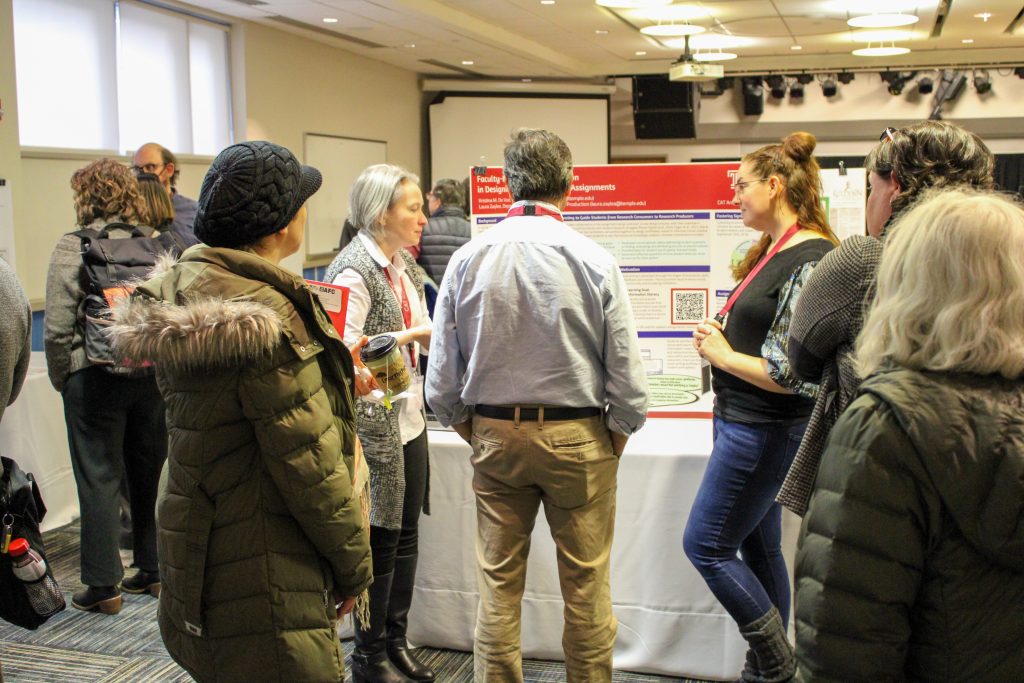

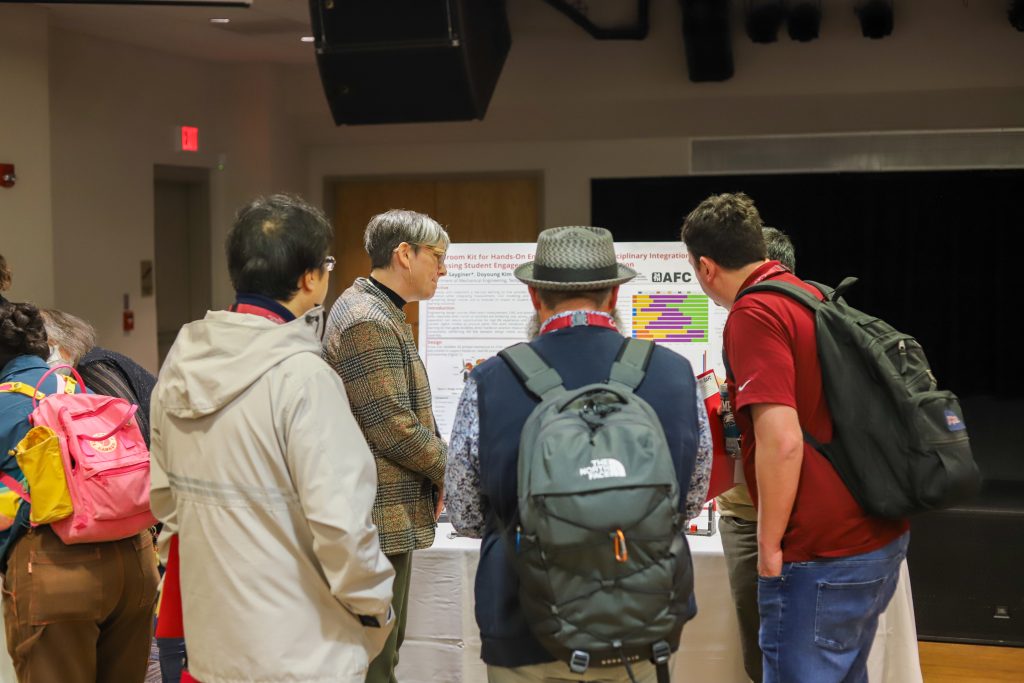

The Teaching Innovation Exhibition combined traditional research poster presentations with instructors demonstrating teaching materials they use in their classroom. Here several conference attendees gather around the poster “Classroom Kit for Hands-On Engineering and Multidisciplinary Integration: Assessing Student Engagement and Learning Contribution” by Dr. Osman Sayginer from the College of Engineering.

Adjacent to the Teaching Innovation Exhibition, attendees could visit an information fair with tables from the TechOWL, the Essential Needs Hub, the Wellness Resource Center, and Disability Resources and Services.

Our plenary speaker on the second day of the conference was Dr. Tia McNair. In her address, Delivering on Pathways to Promise: Intentionality, Inclusion, and Innovation, Dr. McNair argued for the importance of aligning department-level action with institutional priorities. According to Dr. McNair, when the leadership of a university outlines strategic priorities, we need to have discussions in our departments as to what the priority means and how it should shape departmental-level and individual instructor action.

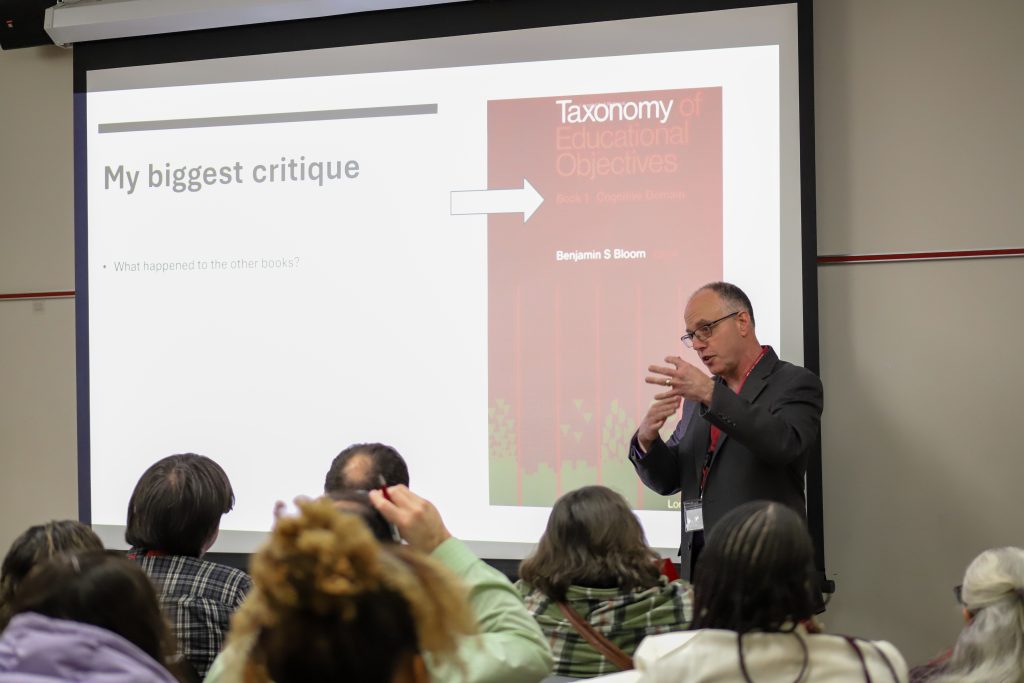

The second day of the conference also featured two rounds of breakout sessions. Here Dr. Pete Watkins of Villanova University leads a session called “Beyond Bloom: The Case of the Missing Taxonomies.”

The final event of the Annual Faculty Conference was our Lightning Talks, where presenters had only fifteen minutes to present their ideas and answer questions from attendees. Above, Dr. Ksenia Power of Temple’s Barnett College of Public Health, presents “Power-Up Learning: Accessible & Meaningful Game-Based Approaches for Today’s Classrooms.”

Many thanks to the CAT’s co-sponsors for their support: Temple Libraries, the Office of Digital Education, Information Technology Services, and the General Education Program.

Thanks to our speakers, Josh Eyler and Tia McNair, and all our great presenters.

Thanks to all the Temple University instructors who took time out of their busy schedules to expand their teaching knowledge.

And thanks to our visitors from sixteen neighboring schools!