by DaVonti’ DeAngelo Haynes, PhD and Linda Hasunuma, PhD

Every four years, the presidential election season presents a unique opportunity for instructors to engage students in deep, meaningful, and transformative discussions about politics in our country and the world. However, the tensions and polarization that come with these elections can also create challenges in our classrooms, whatever the modality. This semester, it is highly likely that political topics and discussions will be part of your classroom environment, whether directly or indirectly related to the course content. To assist with navigating these instances effectively, instructors must employ strategies that foster critical thinking, encourage deep listening, and promote understanding across diverse perspectives. This blog post will provide you with practical tools and strategies for engaging students in these discussions during the election season.

As instructors at a diverse campus such as Temple University, we have a responsibility to cultivate informed and engaged students. Integrating election-related content into your course provides an opportunity for students to develop the skills necessary to be informed leaders and participate thoughtfully in civic life. However, teaching during an election season also requires sensitivity to the diverse backgrounds and perspectives that our students bring with them. Political discussions can quickly become contentious, and faculty must be prepared to manage these “hot moments” while maintaining a respectful and inclusive learning environment for everyone. Faculty must create a safe environment where all students feel comfortable sharing their views, while also ensuring that discussions remain respectful and focused on learning.

We encourage all instructors to think about how this election cycle and the results in November may impact your students emotionally and psychologically; they may have strong feelings, beliefs, attitudes, and reactions to course content and discussions. Acknowledging important current events and topics can help.

Below are some helpful strategies for engaging in discussions about the election:

- Set rules for course dialogue. In a structured dialogue, students are reminded to refrain from speaking without interrupting others and to focus their responses on the issue at hand and critiquing ideas rather than their peers. By creating guidelines together, students feel they have more of a stake in maintaining a respectful learning space.

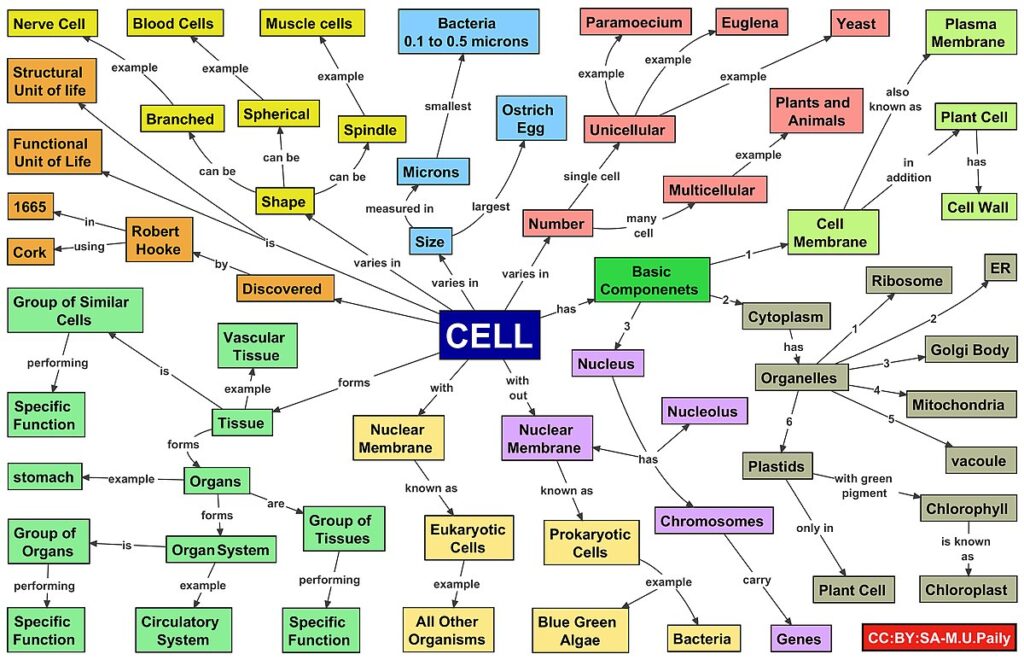

- Use discussion boards to have students think critically and reflect about their own values, lived experiences, and social responsibility. These activities not only engage students in higher-order thinking but also encourage them to contribute to the broader political discourse.

- Ensure, don’t assume that your students have a foundational understanding of elections, such as the structure of the government, the electoral process, and current policy issues/topics.

- Remind students about the importance of analyzing and understanding the different platforms of candidates and parties, comparing their policy proposals and considering their potential impact on them and other populations and communities. You may need to remind your students to focus on the policies and issues rather than solely focusing on the candidate.

- Bring current events into your discussions. Encourage students to introduce current events they’ve read about related to the election that connect to course materials or weekly topics.

Interfaith Philadelphia recommends a technique for engaging in dialogue on contentious issues which assigns roles to groups of 4 participants. One person is the storyteller or speaker and speaks for 2-3 minutes uninterrupted while the other three serve as listeners. Listeners may take notes and are assigned specific tasks: one listens for facts; another listens for feelings; and the third listens for values. After the speaker is finished, each listener shares what they heard with respect to facts, feelings, and values and then the whole group reflects on what they learned from the activity together. By explaining to students that the goal is not to find a solution or settle a debate but to listen for deeper understanding can help generate greater empathy for another’s perspective and lived experience, and strengthen our connection to one another.

Even with thought and care, contentious moments may still arise, however, and these moments can be challenging for students and you as the instructor, but they also have the potential to provide valuable opportunities for learning. In these instances, instructors should acknowledge the emotional intensity of the discussion then use techniques such as pausing the discussion to allow for reflection or reframing and redirecting the discussion to focus on the underlying issues and topics at hand. After these moments, we recommend providing your students with additional resources and readings to dive deeper into the issues.

We also recognize, this election season may not only challenge our students, but also you! Please don’t feel as if you need to be a political expert or have the “perfect” responses to student questions and concerns related to the election or current events. In the coming weeks the Center for the Advancement of Teaching (CAT) and other university offices such as IDEAL will be posting additional tips and resources for teaching during the election and hosting workshops for faculty/instructors to attend. We hope you will join us at one of our workshops listed below or schedule a consultation with one of our educational developers if you seek further support and community around these teaching concerns during election season.

Center for the Advancement of Teaching’s 2024 Election Resource Guide

Temple Votes: An Informational Session (co-sponsored with Temple Votes) Wednesday, September 18, 3:00 – 4:00 PM, Online via Zoom | Details & Registration

Can We Really Talk? The Role of the Media on Class Discussions Involving Race, Religion, and Politics (co-sponsored with IDEAL) Wednesday, September 25, 3:00 – 4:30 PM, TECH 109 | Details & Registration

“The Psychological Drivers of Misinformation Belief and its Resistance to Correction,” A Light Reading Group on Why Misinformation Sticks and What To Do About It Tuesday, October 1, 2:00 – 3:00 PM, Online via Zoom | Details & Registration

Supporting Belonging and Student Mental Well-Being in the Classroom Wednesday, October 2, 3:00 – 4:00 PM, Online via Zoom | Details & Registration

Can We Really Talk? Political Polarization, the Presidential Election, and Preparing for Challenging Discussions (co-sponsored with IDEAL) Wednesday, October 23, 3:00 – 4:30 PM, TECH 109 | Details & Registration

DaVonti’ DeAngelo Haynes, PhD, MS, MSW is Assistant Professor at Temple University’s School of Social Work and Program Director for the Masters of Social Work degree.

Linda Hasunuma, PhD serves as Associate Director of Inclusion Initiatives at Temple’s Center for the Advancement of Teaching.