by Dana Dawson, Ph. D.

With the beginning of the fall semester steadily approaching, you may be pondering how you will address the use of generative AI in your courses. To help with your decision making, AI student guideline drafting as well as activity and assessment designing, we encourage you to take a look back at EDvice Exchange posts on the topic of planning for AI use in your classes.

A Survival Guide to AI and Teaching

Our series “A Survival Guide To AI and Teaching” featured posts on everything from what generative AI is to the ways these tools will impact equity in education.

- What is Generative A.I.?

- Generative AI and Learning: Benefits and Pitfalls

- “Should I Allow My Students to Use Generative AI Tools?” Decision Tree

- Make AI Your Friend

- A Critical Eye on AI

- Creatively Working Around AI

- Inoculating Our Students (and Ourselves!) Against Mis- and Disinformation in the Age of AI

- Academic Integrity and AI: Is Detection the Answer?

- AI and Equity in the Classroom

- Talking to Your Students About AI and Learning

Faculty Adventures in the AI Learning Frontier

Our spring 2024 series “Faculty Adventures in the AI Learning Frontier” showcased how Temple faculty members used and talked about AI in their classrooms during the previous semester.

- AI and (First Year) Writing

- Teaching with Generative AI in Health Sciences Education

- Assignments and Activities that Address Ethical Considerations of Generative AI Use

In the final post in the series, Michael Schirmer, who teaches in the Fox School of Business, shared his experiences with generative AI both with his students and as part of his personal scholarly practice.

Using PI to Manage AI

Our series “Using PI to Manage AI” considered the most fundamental element of addressing AI in our courses: sound pedagogy. Posts in this series focused on evidence-based ways of designing assessments of student learning that encourage academic honesty, motivation, and a desire to learn.

- Designing Meaningful Assessments by Applying the UDL Framework

- Learning Assessment Techniques That Help Build Students’ Self-efficacy

- Iterative Work to Strengthen Student Engagement

- Summative Assessments Can Promote Reflection and Learning, Too!

- Tech Tools to Make Invisible Learning Visible Through Formative Assessments

CAT Tips Season 5 – Generative AI Tools

Finally, our most recent series of CAT Tips, short videos offering teaching tips and suggestions, focused on how generative A.I. tools can be used to support student learning.

- Using AI to Personalize the Student Learning Experience

- AI Tools That Can Assist With Accessibility

- AI as a Personal Tutor or Study Partner

- AI as an Oral Presentation Practice Partner for Students

- Using AI to Offer Students Helpful Studying Alternatives

- Generative A.I. – Process over Product

- AI Uses for Brainstorming and Creative Processes

- AI as a Language Learning Opportunity

- AI for Teachable Moments

- Considerations for using AI as an Aid in Research.

CAT staff are available for consultation throughout the summer. To schedule an appointment, visit our consultation booking page. The CAT’s Ed Tech labs are also open Monday through Friday, 8:30-5 if you’d like to drop in and chat with a staff person about AI tools (or any other educational technology question).

Our Faculty Guide to A.I. webpage features helpful information and resources, including information on Temple’s policy.

We also welcome you to sign up for one of our pre-semester AI workshops.

AI or Nay? Deciding the Role of Generative AI in Your Classroom

Thursday, August 8, 2024, 11:00AM-12:00PM via Zoom

Generative AI tools to help with research, writing, ideation and creative work are now part of our educational landscape and cannot be ignored, but you may be feeling unsure how to address them in your classes. Should you encourage their use but place parameters on how they are used? Will allowing students to use AI tools reduce the efficacy of your classes? Or is AI use now an essential skill for our students? In this workshop, we will explore the implications of allowing students to use generative AI tools and help you work through the question of whether and how you will permit their use in your classes.

AI Assignment Re-Do Bootcamp

Monday, August 12, 2024 and Wednesday, August 14, 2024, 1:00PM-4:00PM, Tech 109

We have been learning more about generative AI tools such as ChatGPT and what it means to teach in a world where generative AI is available to us and our students. In this 2-day intensive workshop, faculty will collaborate to revise and/or develop assignments for the AI era. You will learn how to intentionally leverage AI tools for learning and development as well as how to modify assignments to make them more AI resistant. You will also learn a framework for discussing the assignment and the role of AI in your classroom with students. This is an opportunity for you to develop the best assignments you’ve ever used in your classroom. Bring an assignment you already use and stride boldly into the future with us!

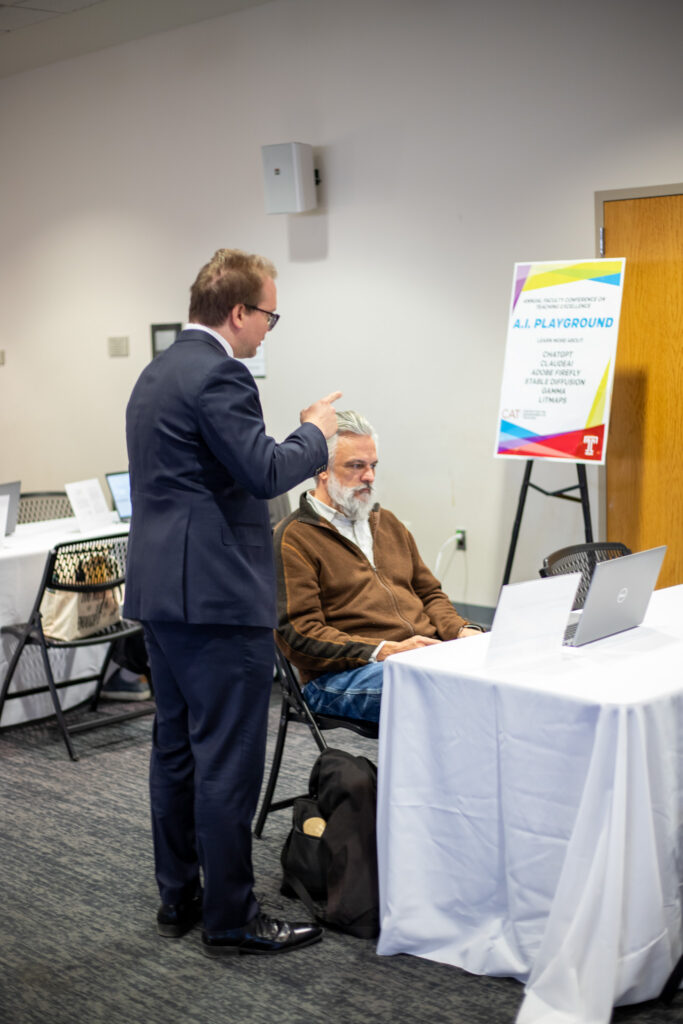

AI Sandbox

Wednesday, August 14, 2024, 12:00PM-1:00PM, Tech 109

Have you been putting off familiarizing yourself with AI tools? Or have you tried some of the more commonly available apps but would like to learn more about the wide variety of tools that are available? Join us for a hands-on exploration of the AI tools that are changing the way we live, work and study.