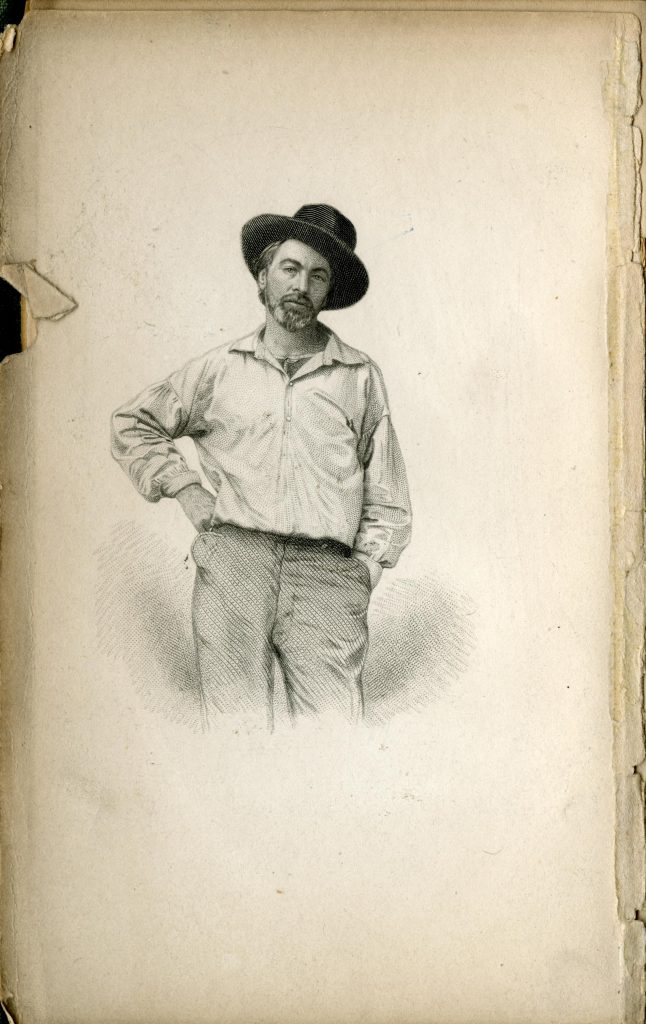

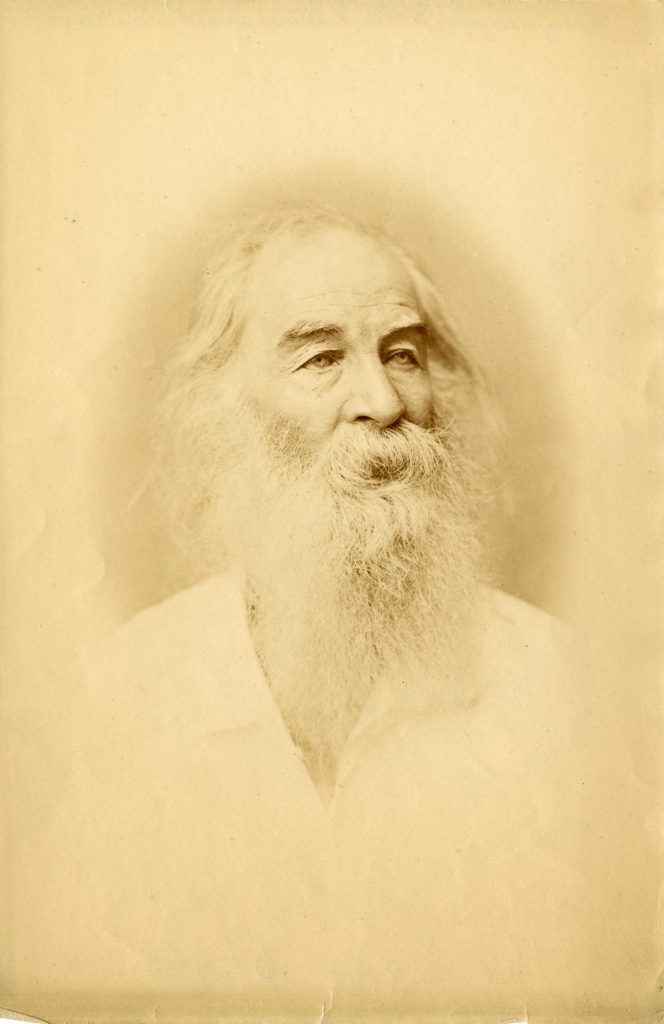

As we anticipate the celebration of the 200th anniversary of Walt Whitman’s birth on May 31, 2019—and the start of the World Series this month—we are reminded of the role the 1988 film Bull Durham played in connecting a new generation to Whitman and his love of baseball.

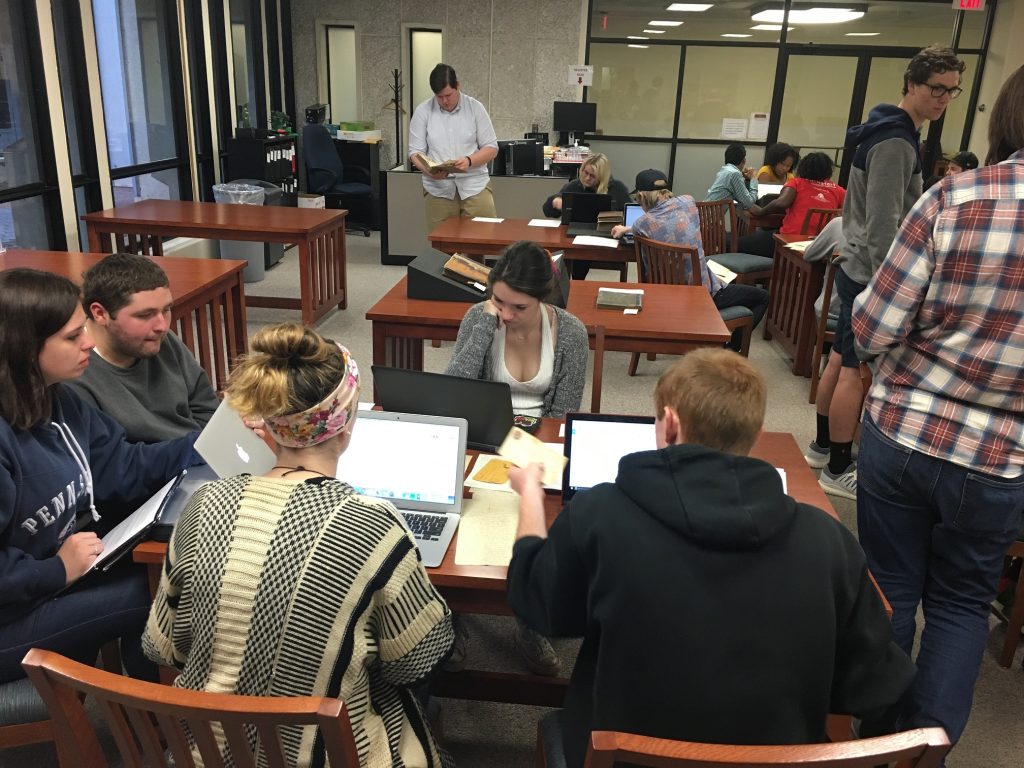

Exhibits and programming scheduled for 2019 will feature the poet and his writings, his Civil War work, and even the controversy around the naming of the Walt Whitman Bridge. But the Special Collections Research Center has the Whitman-baseball connection well-documented in the Traubel Family Papers.

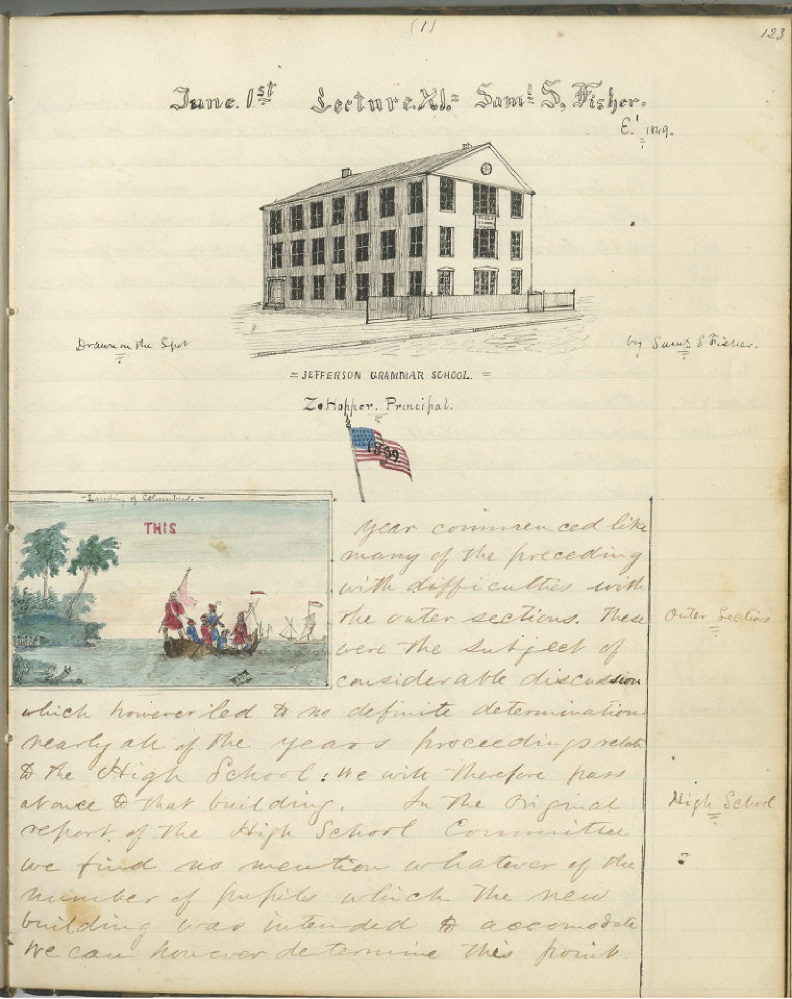

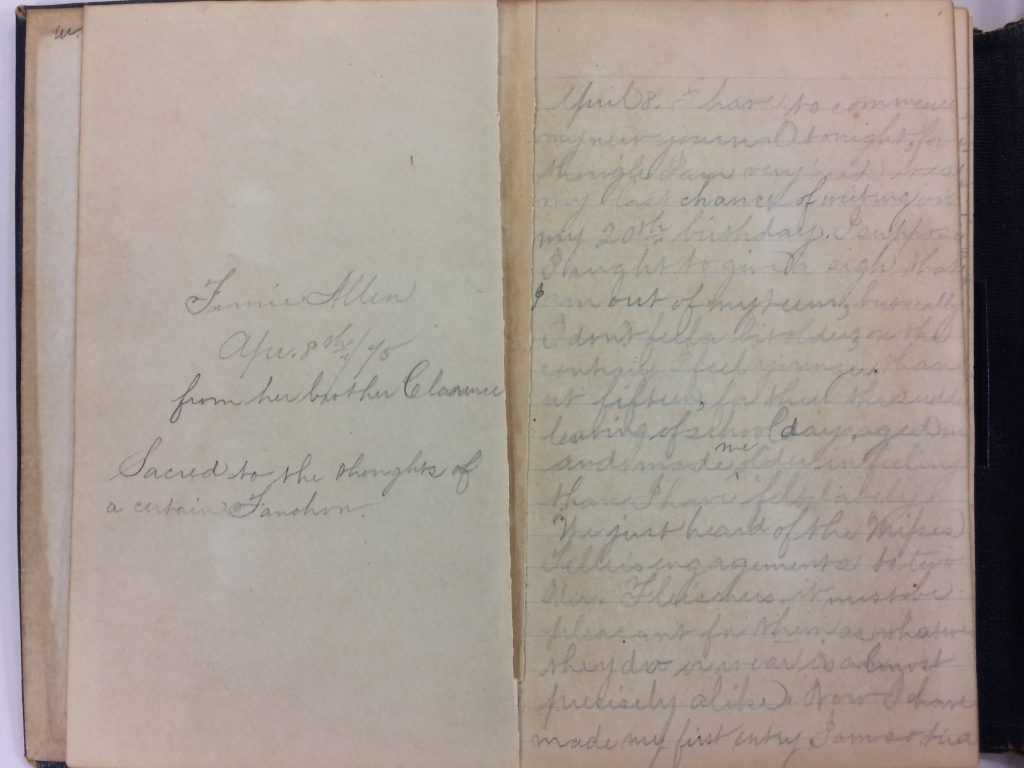

Horace Traubel, a writer and editor, his wife, Anna, and his daughter Gertrude knew Whitman in Camden, NJ, and worked to preserve his memory after his death in 1892. Traubel was one of Whitman’s three literary executors, and the family prepared much of the material for the multi-volume series, With Walt Whitman in Camden.

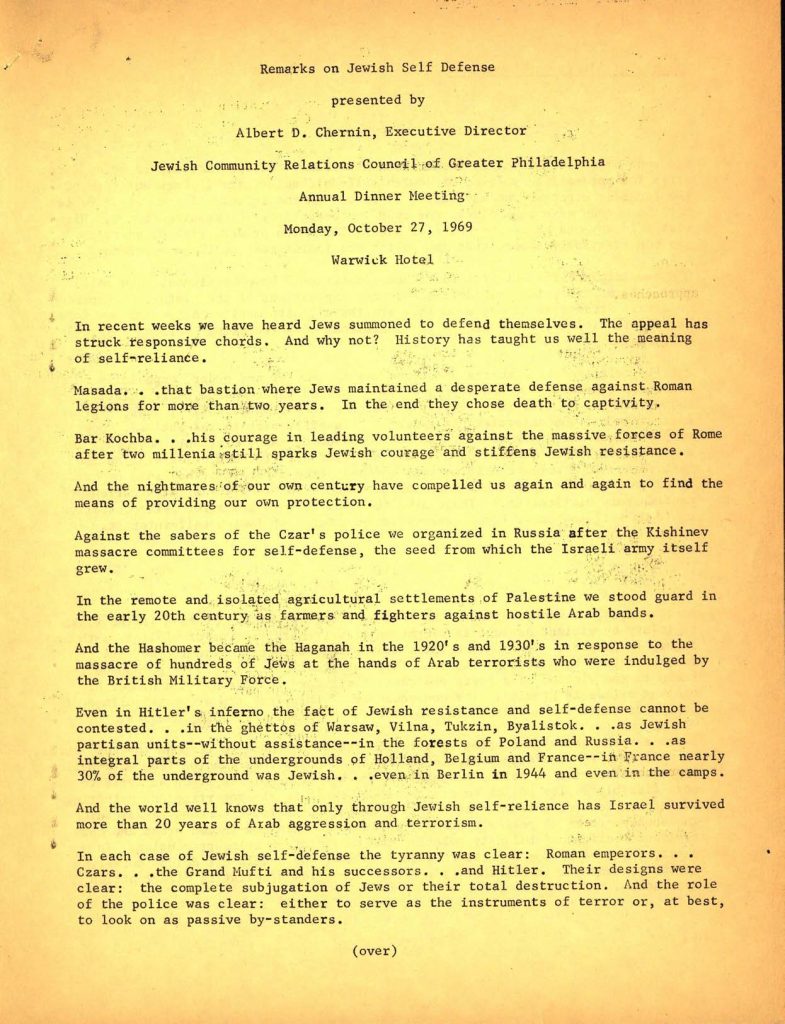

The Bull Durham connection comes when Annie Savoy (mis-)quotes Whitman on baseball. LA Times writer Brian Cronin set about correcting that in a March 28, 2012 article, saying:

“Walt Whitman, the great American poet, essayist and journalist (best known for his poetry collection, Leaves of Grass), is referenced again in Bull Durham, at the very end of the film, as Annie speaks to the audience, saying, “Walt Whitman once said, ‘I see great things in baseball. It’s our game, the American game. It will repair our losses and be a blessing to us.’ You could look it up.” “

Cronin points his readers to a quote from Horace L. Traubel With Walt Whitman in Camden, vol. 2 (stated by Whitman in September 1888):

“I like your interest in sports ball, chiefest of all base-ball particularly: base-ball is our game: the American game: I connect it with our national character. Sports take people out of doors, get them filled with oxygen generate some of the brutal customs (so-called brutal customs) which, after all, tend to habituate people to a necessary physical stoicism. We are some ways a dyspeptic, nervous set: anything which will repair such losses may be regarded as a blessing to the race. We want to go out and howl, swear, run, jump, wrestle, even fight, if only by so doing we may improve the guts of the people: the guts, vile as guts are, divine as guts are!”

Cronin goes on: “Later on,… in Volume 4 (published after Traubel’s death), Whitman spoke more about baseball (this time in April of 1889):

“Baseball is the hurrah game of the republic! That’s beautiful: the hurrah game! well—it’s our game: that’s the chief fact in connection with it: America’s game: has the snap, go, fling, of the American atmosphere—belongs as much to our institutions, fits into them as significantly, as our constitutions, laws: is just as important in the sum total of our historic life.”

You could look it up.

–Margery Sly

Director, Special Collections Research Center