I promised a “provocative” discussion at yesterday’s Assessment Community of Practice gathering, and I think we met that goal. The attendance was good, at least, with 27 staff members from across the library (13 departments represented). A few highlights and editorial comments:

Impact

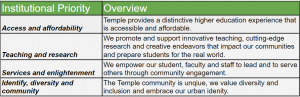

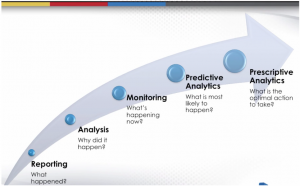

We often talk of impact as a way of measuring success as we work towards our goals. Impact can be a tricky thing to measure, and a single project may have different impacts, depending on the audience. Take our Open Access initiatives: From the student, or institutional perspective, impact for the open access textbook project is the dollar amount saved students. From the Library’s perspective, the impact is how open access ideas are advanced among Temple faculty. The Research Data Services’ data grants program is another example. We can count the number of applications received for the first year. That’s one measure. But we must also consider the increased awareness among faculty of the new ways in which the Library provides resources for their research. Harder to measure, but equally important.

Team Operations

The Strategic Steering Teams set goals and assess those, but also consider how the team functions as an organizational structure. To get those conversations going, leads periodically ask of the team:

- How do you feel things are going?

- Are you doing too much or not enough?

- What changes would you like to see?

As a result, teams decide together how often to meet, and what the nature of their work together should look like. We learned that each team has evolved in its own way, from serving as an advisory body to carrying out projects with “all hands on deck”.

“What makes a strategic steering team any different than a committee?”

Merely being a cross-functional group is not enough. Focusing effort on areas of strategic importance happens elsewhere as well (thinking of the Web work now). In my mind, the autonomous nature of the teams is important. Each team begins its formative work by writing a charge – that process of creating a shared vision for the purpose of the team is one that is designed to bring the group together. It’s based on research : environmental scans both internal (where do we need to go?) and external (what are other libraries doing in this area?) Team members are asked to think holistically when setting goals and to consider impact when prioritizing those goals. We take the concept of Team to heart, sharing with team participants the seminal article, The Discipline of Teams as well as other resources for building teams.

We celebrate the collaborative, creative work that the teams are doing across the organization. Scholarly Communication met with Collections Strategy to talk open access. Research Data Services also collaborated with Collections on their data purchase initiative. Outreach & Communication’s popular Ask Me Anything on Slack program serves the entire library/press. The youngest team, Learning & Student Success, includes a member from the Writing Center, bringing a fresh perspective to that work. I think the idea of continuous reflection on our own structures is important. And while all of these elements are present in the group work we do across the organization, the Strategic Steering teams help to focus energies in a directed, yet flexible way towards library/press wide strategic goals.

But there are clear challenges

Membership is a big one. How do we retain cohesion within the team but allow for fresh voices? How do we open up this kind of participation to staff at all levels? How do we resource the teams with dedicated staff time and potential dollars? How might we empower teams with more decision making authority in their areas of expertise?

The meeting was open to all staff. An open meeting that surfaces challenges to an organizational structure, I believe, is pretty special. Messy, yes, but an opportunity to learn as well. Thanks must go to the Strategic Team leaders, to the many team members, and all who joined us for the session.