Temple’s Resident Librarian program is now in its third year, and we have started the recruiting process for our 2nd cohort of resident librarians. I sat down with the program administrators Richie Holland, Director of Administration, and Sandi Thompson, Head of the Ambler Branch library, to learn more about how they incorporate an assessment process to insure that this important initiative is successful.

NT: Tell me a little about the resident librarian program here at Temple. What was the impetus for initiating the program?

RH: Well, this has been on my back burner for a long time. The University of Delaware had a long standing program named in honor of civil rights leader and historian, Pauline A. Young. Here at Temple Libraries, our overall goal is to provide mentoring and support the diversification of librarians in the profession.

As the library’s Human Resources person, I’ve attended several meetings at ALA and I participate in the ACRL Residency Interest Group. I reached out to colleagues at other institutions with programs like this, and also talked with participants in resident programs. There is a bit in the formal literature, but most of my “research” was talking with others with experience.

ST: And then we also had the Temple/Drexel/Penn staff development day, with Jon Cawthorne. He’s also part of the ACRL Diversity Alliance.

NT: What does a successful program look like? What are you aiming to accomplish?

ST: We want to instill in our resident librarians confidence as they move into a career position. They will have experience in several areas of librarianship, and have solid accomplishments, or projects that they’ve completed. They know what it takes to be a professional. And of course we want them to thrive in their next professional job.

We had to think about how best to accomplish this. For instance, we deliberately organized the program to fit the interests and needs of the resident. They take responsibility for developing a program tailored to their interests and the experience they want. Then we provide them with lots of support – regular meetings with us, with their mentors, with site supervisors, and healthy travel support. We picked the brains of residents at other libraries on how to structure our program to make it really attractive to prospective applicants. One thing that came out loud and clear was to hire more two, providing the librarian with a ready cohort.

Once our resident librarians were in the program we set up different ways of “checking in” with them to insure all was going smoothly. For each rotation, the librarians wrote up their experiences, and we talked with site supervisors about what was working; the strengths and weaknesses for each experience.

NT: I know you have been carefully tracking on the program over the last two years. Tell me about some changes you are making this next cycle, based on that experience.

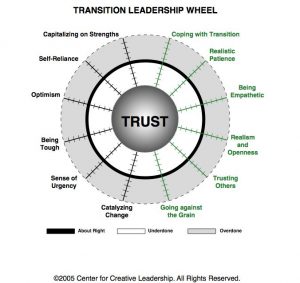

RH: Yes, we asked the current residents to provide us with feedback, as well as others involved with Temple’s program. We made a couple changes to the job description. For instance, candidates need to know they will be working with diverse management styles, and be amenable to that. Of course, that flexibility is a life-skill for all of us. Since we’re building a culture of assessment here at Temple, we added language about decision-making informed by data.

We want to recruit candidates who are a good fit for these positions, and having the right job description gives a more accurate sense of what the resident experience is like.

We’re also evaluating the timing of the different rotations – we did four, some libraries do as many as five. We want the librarians to have adequate time to complete a substantive project in their rotations. Then of course in their second year they stay in one department.

With each step of the process, from recruitment to the program structure itself, we’re continually tweaking, to make sure it works for everyone.

NT: We don’t always think of “assessment” taking place in the HR area, but you both have modeled a process that fits that definition – you identified a goal, or something you wanted to accomplish, you conducted research into other programs, you set up the program and sought feedback continuously and from multiple sources on how well the program was working and how it could be improved, and then finally, you are making adjustments to improve the program going forward.

So thanks for sharing the process.