Today’s post is contributed by Olivia Given Castello, Tom Ipri, Kristina De Voe and Jackie Sipes. Thank you!

The sudden move to all-online learning at Temple University presented a unique challenge to the Libraries and provided a great opportunity to enhance and assess our virtual reference services. Staff from Library Technology Development and Learning and Research Services (LRS) put into place a more visible chat widget and a request button for getting help finding digital copies of inaccessible physical items.

Learning & Research Services librarians Olivia Given Castello, Tom Ipri, and Kristina DeVoe, and User Experience Librarian Jackie Sipes have been involved in this work.

Ways we provide virtual reference assistance

We are providing virtual reference assistance largely as we already did pre-COVID-19. We offer immediate help for quick questions via chat and text, asynchronous help via email, and in-depth help via online appointments. See the library’s Contact Us page for links to the many ways to get in touch with us and get personal help.

Our chat service now integrates Zoom video chat and screensharing. That was part of a planned migration that was completed just before the unexpected switch to all-virtual learning.

Since going online-only, we have also launched a new access point to our email service. By clicking the “Get help finding a digital copy” button on item records in Library Search (Figure 1), patrons can request personal help finding digital copies of physical items that are currently inaccessible to them.

Usage this year compared to last year

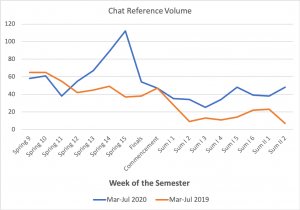

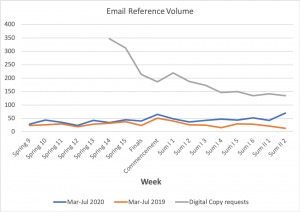

The main difference we’ve seen since going online only has been in the volume of virtual reference assistance we are providing. We added a more visible chat button to the library website and Library Search. Since making that live, we have seen 88% more chat traffic than during the same period last year (Figure 2). The “Get help finding a digital copy” button also led to an enormous increase in email requests (Figure 3). Since that was launched we have seen more than a sevenfold increase in email reference. At the height of Spring semester, we received 347 of these requests in one week.

Figure 2. Volume of chat reference transactions compared for the same weeks of Spring/Summer semester in 2019 and 2020.

Figure 3. Volume of email reference transactions compared for the same weeks of Spring/Summer semester in 2019 and 2020.

Our team has handled this increased volume very well. When we first went online-only we made the decision to double-staff our chat service, and that turned out to be wise. We also have staff from other departments (Access Services and Health Sciences) single-staffing their chat services so that we can transfer them any chats that they need to handle, or transfer them chats if there happen to be many patrons waiting.

Email reference handling is part of the chat duty assignment, so the double-staffing has also served to help handle the increased email volume. Outside of chat duty shifts, the two other disciplinary unit heads (Tom Ipri and Jenny Pierce) and I are doing extra work to handle emails that come in overnight. Our two part-time librarians, Sarah Araujo and Matt Ainslie, both handle a large volume of chat and email reference and we are grateful for their support.

Types of questions we receive

Since April, about 75% of email reference requests are for help finding digital copies of books and media submitted through our “Get help finding a digital copy” button that is embedded in only one place: Library Search records. The remaining 25% include a diverse range of questions about the library and library e-resources.

The topics patrons ask about in chat and non-“Get help finding a digital copy” email reference vary somewhat depending on the time of year. Overall, about 40% of the questions patrons ask are about access to materials and resources, particularly articles. About 5% of questions appear to come from our alumni, visitors, and guests, which shows that outside communities seek virtual support from us.

During the period since we’ve been online-only, we received questions that mirror the proportions we’ve seen all year long. However, 45% of the alumni/visitor/guest questions, and about 44% of the media questions, we have received this year have been during the online-only period.

Analyzing virtual reference transactions to understand user needs

Our part-time librarians, Sarah Araujo and Matt Ainslie, led by librarian Kristina De Voe, have created and defined content tags for email tickets and chat transcripts. They systematically tag them on a monthly basis, focusing on the initial patron question presented, and have also undertaken retrospective tagging projects. The tagging helps to reveal patterns of user needs over time. For example, reviewing the tags from questions asked during the first week of the Fall semester in both 2019 and 2018 show a marked increase in questions related to ‘Borrowing, Renewing, Returning, and Fines’ in 2019 compared to the prior year. This makes sense given the move to the new Charles Library, the implementation of the BookBot, and the updated processes for obtaining and checking out materials (Figures 4 and 5).

![Figure 4. Tagged topics represented during the first week of Fall 2019 semester [Aug 26 - Sept 1, 2019]. Number of chats & tickets: 125. Number of tags used: 144.](https://sites.temple.edu/assessment/files/2020/07/TaggedTopics2019-300x155.png)

Figure 4. Tagged topics represented during the first week of Fall 2019 semester [Aug 26 – Sept 1, 2019]. Number of chats & tickets: 125. Number of tags used: 144.

![Figure 5. Tagged topics represented during the first week of Fall 2018 semester [Aug 27 - Sept 2, 2018]. Number of chats & tickets: 107. Number of tags used: 136.](https://sites.temple.edu/assessment/files/2020/07/TaggedTopics2018-300x168.png)

Figure 5. Tagged topics represented during the first week of Fall 2018 semester (Aug 27 – Sept 2, 2018). Number of chats & tickets: 107. Number of tags used: 136.

![(Figure 6. Word cloud of approximately 100 most frequently used words in chat transcripts during the move to online-only period [March 16-June 30, 2020]).](https://sites.temple.edu/assessment/files/2020/07/WordCloud-1-300x162.png)

Figure 6. Word cloud of approximately 100 most frequently used words in chat transcripts during the move to online-only period (March 16-June 30, 2020.

With a colleague from Access Services, Kathy Lehman, we also analyzed email transcripts from this academic year in order to refine our process for passing reference requests between LRS and Access Services.

We do not systematically re-read email and chat transcripts beyond discrete projects like this, except when there is some new development related to a particular request that requires we review the request history.

We analyze anonymous patron chat ratings and feedback comments, as well as patron ratings and comments from the feedback form that is embedded in our e-mail reference replies. Some librarians also send a post-appointment follow-up survey, and we analyze the patron ratings and comments submitted to those as well. Patron feedback from all these sources has so far been overwhelmingly positive.

Changes to the service based on our analyses

We have refined our routing of email requests, and chat follow-up tickets, based on what requests we are seeing and the experiences of staff. In our reviews of “Get help finding a digital copy” requests at two points in time, we made suggestions to staff members as a result of our review at Time 1. Then we later found there was an improvement in request handling at Time 2, as a result of these adjustments.

We developed a suite of answers, as part of our larger FAQ system, and engineered them to come up automatically when we answer an email ticket. This saves our staff time, since they can easily insert and customize the text in their replies to patrons.

Guidance for referring to Access Services was improved, particularly when it came to referring patrons to ILLiad for book chapter and journal article requests and Course Reserves for making readings available to students in Canvas. We have also streamlined how we route requests that turn into library ebook purchases or Direct to Patron Print purchases, and we are working with Acquisitions on a new workflow that will proactively mine past “Get help finding a digital copy” request data for purchase consideration.

Using virtual reference data to learn about the usability of library services

Analyzing virtual reference transactions can also provide insight into how users are interacting with library services more generally, beyond just learning and research services. Throughout spring and summer, virtual reference data has informed design decisions for the website and Library Search.

One example is the recent work of the BookBot requests UX group. The group, led by Karen Kohn and charged with improving item requests across physical and digital touch points, used virtual reference data to better understand the issues users encounter when accessing our physical collections. This spring, we focused on how we might clarify which items are requestable in Library Search and which items require a visit to our open stacks — an on-going point of confusion for users since Charles Library opened.

The data confirmed that the request button does create an expectation that users can request any physical item. Looking at the transactions, we also saw that users did not mind having to go to the stacks, but they simply didn’t always understand the process. We realized that our request policies are based on the idea of self-service — if a user can get an item themselves, it is typically not requestable. One outcome of this work is new language in the Library Search request menu that instructs users about how to get items from the browsing stacks themselves.

Next steps for assessing virtual reference service

We are working on several other initiatives this summer. One is a project to test patron’s ability to find self-service help on our website. Hopefully it will lead to suggestions for improvement to our self-service resources and placement of online help access points. We have also made revisions to the “Get help finding a digital copy” request form based on feedback from staff, and changes to the placement of the request button are planned related to our Aug. 3 main building re-opening. It will be helpful to test these from the user perspective once they are live.