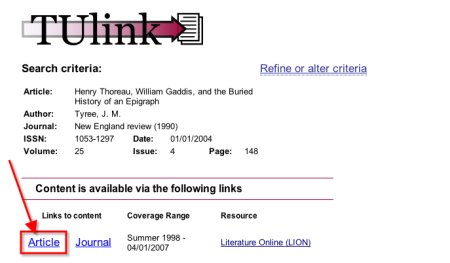

Google Scholar has become a useful search tool because it allows you to search across the content of many different databases, including JSTOR, Project MUSE, Blackwell Synergy, Cambridge Journals Online, SpringerLink, HighWire Press, Journals@Ovid Full Text, Sage Journals Online, ScienceDirect, and many more. That is not to say that the entire content of these databases is available through Google Scholar (which has never released a complete list of its sources or the extent of its coverage) but at least some of it is there. Google Scholar also includes books from Google Book Search in its search results. Up till now, one of the problems with Google Scholar for Temple students, faculty, and staff has been the difficulty in retrieving the full-text of articles. You might find a juicy article in Google Scholar but after clicking on the link get a message that the article is blocked, even for many databases that you know Temple subscribes to. Well, this process has just gotten a whole lot easier. Now Temple has registered its TUlink service with Google Scholar, which means that you can link directly from Google Scholar into the library’s subscription databases. Look for Find Full-Text @ TU right after the article title and click on it. You will see the TUlink interface pop up with links for full-text if we have it online or in print, or a link to Temple’s Interlibrary Loan Form if we don’t. From within any of Temple’s campuses, links to Find Full-Text @ TUwill appear automatically. From off-campus you need to do one of two things:

- Just click HERE and it will automatically set your Google Scholar preferences for Find Full-Text @ TU, or

- Go into the preferences of Google Scholar and select Temple University from LIbrary LInks.

You will find that Google Scholar is a nice addition to your research toolkit. Including it when researching a subject often brings some unusual and unexpected results. Set up your Find Full-Text @ TU preference and give it a whirl. Find Full-Text @ TU will NOT appear for books. For books, click on the link to Library Search at the bottom of the citation. This will take you to the record of the book in WorldCat.org, where you can input a local zip code (Temple’s is 19122) to find a local library with the book. You can set your Google Scholar preferences to use Refworks as your citation manager. In Google Scholar Preferences, just select Refworks as the Bibliography Manager. –Fred Rowland