On Christmas Day 1979, Mr. and Mrs. John Boston of the Alleyne Memorial AME Zion Church in West Philadelphia welcomed several Vietnamese refugees into their home for dinner. Earlier in the month, some 200 refugees accepted an invitation to attend services in their church. Part of the Human Relations Program, these inclusive gestures were coordinated by the Nationalities Service Center (NSC) in cooperation with numerous neighborhood associations, churches, social service organizations, and city departments. The program aimed for community involvement in refugee resettlement. It developed out of necessity, as tensions were mounting in neighborhoods into which thousands of Southeast Asian refugees settled in just a few years.

Ongoing conflict and political upheaval in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos contributed to a worldwide refugee crisis in the late 1970s. By 1980, NSC—just one of several area refugee resettlement agencies—had resettled over 3000 Southeast Asian refugees in Philadelphia, with a commitment to settle 75 people per week going forward. NSC settled the refugees primarily in West and North Philadelphia, where apartments were available and rents were low.

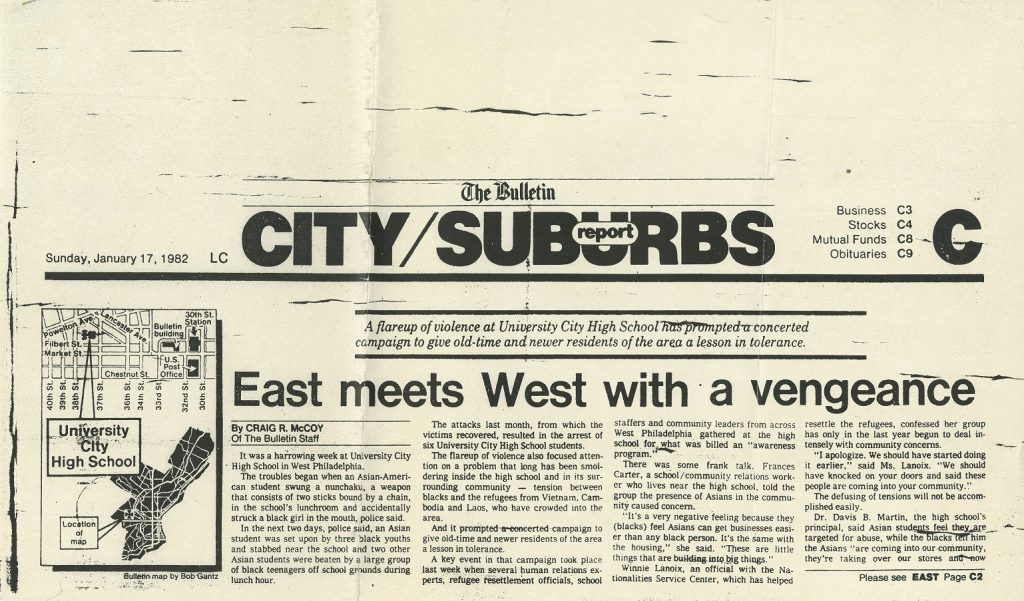

NSC did not consult or alert West or North Philadelphia residents to the influx of refugees, nor were the residents made aware of the political circumstances of their dislocation. Refugees, many of whom were from rural areas in their countries of origin, in turn were not initially educated in the workings of life in a modern American city or the culture of the neighborhoods into which they settled. The language barrier exacerbated matters. At University City High School, existing students misconstrued an ESL program established to assist SEA students as favoritism that gave them an unfair advantage. In Walnut Hill, NSC unknowingly placed refugees in apartment buildings deemed unfit for habitation and inadvertently undermined a boycott of the Dorsett apartment building.

Refugees were reportedly harassed and robbed on the streets, neighborhood associations began to complain, and a general sense of anger and resentment permeated the neighborhoods. Several task-forces involving NSC, other resettlement agencies, assorted city and state departments, and social service organizations assembled in the city. What the media reported as racially motivated discord, NSC saw as a “human relations problem,” one that could be solved with education and community involvement.

NSC’s Human Relations Program officially ran from 1979 to 1980, organizing events and programs to bring the SEA and other refugees together with their new communities. There was a cultural performance festival held that aimed to teach refugees about American culture. It included dancing, drama, singing, and disco. A field trip to a Phillies game, a summer sports program for children, block parties, and a church social at the Mount Carmel Baptist Church were also among the program’s offerings.

Ultimately, NSC and the other task forces working on the issue found that “…public relations is of primary importance. Once informed about the refugees, most communities are receptive.” It was an important lesson to learn at the time. In addition to SEA refugees, private sponsors and settlement agencies were also contending with thousands of Cuban and Haitian refugees. In an effort to improve their ongoing resettlement work, at the conclusion of the Human Relations Project NSC planned to maintain project staff to continue hands-on community work. The Task Force on Inter-Group Crisis, of which NSC was a part, was also discussing a “comprehensive resettlement program and conflict avoidance…”.

Of the many groups involved in ameliorating the refugee resettlement crisis, the Special Collections Research Center holds the archives of the Nationalities Services Center Records, Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, Spruce Hill Community Association, West Philadelphia Corporation, and others.

–Courtney Smerz, Collection Management Archivist, SCRC