When the world thinks of America, one of the first images they conjure is the giant, green hued statue of a woman perched atop her pedestal on Ellis Island. She carries a tabula ansata in the crook of her left arm, and her right hand holds a torch high above her head. She has a noble face, and green spikes create a halo around her head. This figure is the Statue of Liberty, and with its placement on Ellis Island, the gateway to America for millions of European immigrants from 1892 to as recently as the 1950s, it became emblematic of opportunity and new beginnings. However, the statue in its beginnings was not necessarily supposed to represent opportunity but rather liberty and the ideals of republicanism.

When the world thinks of America, one of the first images they conjure is the giant, green hued statue of a woman perched atop her pedestal on Ellis Island. She carries a tabula ansata in the crook of her left arm, and her right hand holds a torch high above her head. She has a noble face, and green spikes create a halo around her head. This figure is the Statue of Liberty, and with its placement on Ellis Island, the gateway to America for millions of European immigrants from 1892 to as recently as the 1950s, it became emblematic of opportunity and new beginnings. However, the statue in its beginnings was not necessarily supposed to represent opportunity but rather liberty and the ideals of republicanism.

In 1865, Edouard Laboulaye, a French political figure, proposed that France gift the United States with a statue representing liberty and the ideals of a republic in honor of the U.S.’s upcoming centennial celebration. Ten years later the French sculptor Frederic Auguste Bartholdi, who had a fascination with “colossal” works, was commissioned by France to design a statue for the United States. The U.S. and France agreed that while France would make the statue itself, the U.S. was responsible for building its pedestal.

Bartholdi and Laboulaye both wanted the statue to represent American ideals. They chose to make the statue a colossal figure of Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom. According to myth surrounding the statue, Bartholdi supposedly had his mother Charlotte sit as the model for the statue’s solemn, simple face. The symbolic torch and tabula ansata were included to represent the ideals of a republic—ideals that France and the U.S. both shared. The statue’s feet were to stand on a broken chain representing freedom from monarchy. Though the statue was supposed to be completed for the U.S.’s centennial celebration in 1876, fundraising and construction for both the pedestal and statue took too long. Thus, the statue and pedestal were ready to be dedicated 10 years after the centennial in 1886.

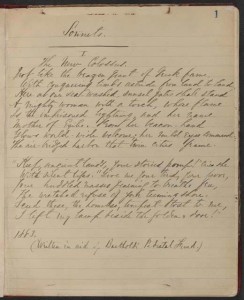

Three years before the dedication, in 1883, Emma Lazarus, a poet and New York native, penned a sonnet to donate to an auction raising money for the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal fund. In this poem, called “The New Colossus,” she describes the massive copper-plated statue as the “Mother of Exiles” welcoming immigrants to America on her perch on Ellis Island. The poem initially held very little significance to the overall story of the Statue; while Lazarus’ sonnet was read on the day of the statue’s dedication, it then went almost completely ignored—that is, until Lazarus’ friend Georgina Schuyler began an endeavor to memorialize the sonnet. By 1903, Shuyler’s efforts had been successful and a plaque of the sonnet was placed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.

Three years before the dedication, in 1883, Emma Lazarus, a poet and New York native, penned a sonnet to donate to an auction raising money for the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal fund. In this poem, called “The New Colossus,” she describes the massive copper-plated statue as the “Mother of Exiles” welcoming immigrants to America on her perch on Ellis Island. The poem initially held very little significance to the overall story of the Statue; while Lazarus’ sonnet was read on the day of the statue’s dedication, it then went almost completely ignored—that is, until Lazarus’ friend Georgina Schuyler began an endeavor to memorialize the sonnet. By 1903, Shuyler’s efforts had been successful and a plaque of the sonnet was placed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.

Since then, Lazarus’ “The New Colossus” has become synonymous with the Statue of Liberty and immigration to America. Through the poem, Lazarus gives the Statue of Liberty a voice:

“Keep, ancient lands, your stories pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!” (1883)

Thanks to the poem greeting all immigrants coming ashore in New York, the Statue became a more than a symbol of liberty and the republic, as was originally intended. Rather, it became many immigrants’ first memory of their new life and the world of opportunity that awaited them. The language in Lazarus’ poem transformed the centennial gift into an emblem of a new life and a chance to pursue one’s dreams.

The Statue of Liberty’s change in meaning parallels the stories of other U.S. icons, such as the Liberty Bell. Like the Bell, the Statue did not take on the meaning it has today until literature was created surrounding it, popularizing one author’s perceived meaning of the monument. And just as the Bell represents both Philadelphia and the U.S., the image of the Statue of Liberty can be synonymous with both New York City and the U.S. at large. But perhaps the popularity of these icons as tourist attractions in their respective cities has simply changed the way we view them altogether. While they may once have been symbols of freedom, liberty, hope, opportunity, and the like, they now mostly represent the places in which they reside. Where once thousands of people gathered below the Statue of Liberty to enter the U.S. as citizens, the tourists who flock to see this monument have become the new “huddled masses.”

Pictures:

“The New Colossus” manuscript – http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/haventohome/images/hh0041s.jpg

Statue of Liberty Tourism – http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2009-07/05/xin_422070605080848438046.jpg

References

“A Timeline of Statue of Liberty.” (2016). The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/statue-of-liberty-timeline

Conradt, S. (2013). “10 Things You Didn’t Know About the Statue of Liberty.” Retrieved from http://mentalfloss.com/article/51521/10-things-you-didnt-know-about-statue-liberty

“Immigration Timeline.” (2016). The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/immigration-timeline

Lazarus, E. (1883). “The New Colossus.” Retrieved from http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/175887

“Libertas.” Encyclopedia Brittanica. 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

“Statue History.” (2016). The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/statue-history

Young, B.R. (1997). Emma Lazarus in Her World: Life and Letters. The Jewish Publication Society, p. 3.

![]() When you think of the Liberty Bell you think of liberty (obviously), freedom, and of course Philadelphia. The history of the Liberty Bell can be trace back to colonial America. It comes from a long line of myths and truths. Gary Nash touches on these myths and truths about the “Old Bell”. One tale that Nash talks about is how the Liberty Bell was used to “announce the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, and thus became the “Independence Bell” or the “Liberty Bell” built on a growing identification of the Old Bell as a symbol of liberty” (Nash, 40). Other stories talk about how abolitionists from New York and Boston used the Liberty Bell as a symbol of freedom. Yet, at the end of the day, no matter what story is told the Liberty Bell stands for liberty and freedom for all.

When you think of the Liberty Bell you think of liberty (obviously), freedom, and of course Philadelphia. The history of the Liberty Bell can be trace back to colonial America. It comes from a long line of myths and truths. Gary Nash touches on these myths and truths about the “Old Bell”. One tale that Nash talks about is how the Liberty Bell was used to “announce the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, and thus became the “Independence Bell” or the “Liberty Bell” built on a growing identification of the Old Bell as a symbol of liberty” (Nash, 40). Other stories talk about how abolitionists from New York and Boston used the Liberty Bell as a symbol of freedom. Yet, at the end of the day, no matter what story is told the Liberty Bell stands for liberty and freedom for all.![]()

According to author Jill Ogline, the reason the Liberty Bell has become one of America’s most important and well recognized icons is because it is “a tangible “piece of history” electrified by a surrounding web of legend” (Ogline, 52). A much larger icon that could be described in a similar fashion is Ellis Island, the checkpoint for immigration into the land of the American dream from 1892- 1954. As visitors walk the halls of this isolated landmark, they are taken back to a time where people from all around the world believed that America, particularly New York, was a place where the streets were lined with gold and and the job opportunities were endless. This site continues to be a mecca that Americans are willing to travel to see because “the desire for an emotional connection with the past is a prime motivator in drawing visitors to historic sites”.

According to author Jill Ogline, the reason the Liberty Bell has become one of America’s most important and well recognized icons is because it is “a tangible “piece of history” electrified by a surrounding web of legend” (Ogline, 52). A much larger icon that could be described in a similar fashion is Ellis Island, the checkpoint for immigration into the land of the American dream from 1892- 1954. As visitors walk the halls of this isolated landmark, they are taken back to a time where people from all around the world believed that America, particularly New York, was a place where the streets were lined with gold and and the job opportunities were endless. This site continues to be a mecca that Americans are willing to travel to see because “the desire for an emotional connection with the past is a prime motivator in drawing visitors to historic sites”. oms and buildings where the sick and disabled were left behind for “treatment” and “rehabilitation” are not only off limits, but they have been neglected to the point of significant decay, essentially erasing that part of the story.

oms and buildings where the sick and disabled were left behind for “treatment” and “rehabilitation” are not only off limits, but they have been neglected to the point of significant decay, essentially erasing that part of the story.