VS.

Just last month, Chloe Kim became the youngest gold medal winner in Olympic women’s snowboarding history at 17 years old. She won first place in the women’s halfpipe event and brought the gold medal from PyeongChang home to the United States. This achievement was apparently significant enough to raise her status to Barbie-worthy. Kim is now featured as part of the Role Models line of Barbie dolls, alongside other female professionals like conservationist Bindi Irwin, model and body activist Ashley Graham, and historic aviator Amelia Earhart.[1] In bold pink letters on the Role Models page at barbie.mattel.com, one can read the statement “Imagining she can be anything is just the beginning. Actually seeing that she can makes all the difference.” The idea that Barbie can show young girls all they can possibly become is nothing new. Barbie has always set out to teach girls “independence” and “all that [they] could be.”[2] It was a major point for Mattel that the Barbie doll did not “teach [girls] to nurture”[3] or do housework, but rather to pursue careers outside the home and become strong women. But why was there a need or want for a toy to teach children this lesson? Well, that’s because many other toys girls were playing with were painting a much different picture of women’s place in society.

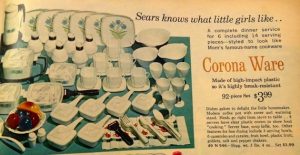

Many a childhood, especially those of the female population, included toys like kitchenware, vacuums, baby dolls and the like. I, for one, played house many times in my day. For nearly a century, toys that simulate or depict domestic chores and housekeeping items, the “rough housework”[4] Barbie didn’t do, have been marketed to American girls. For example, an article by Elizabeth Sweet, a sociologist, wrote an article for The Atlantic that highlights Sears ads from 1925 and 1965 that market domestic tools like brooms and sewing machines and cookware, claiming, “Every little girl likes to play house, to sweep, and to do mother’s work for her.”[5] These types of toys worked to make a young girl into a “little homemaker”[6] rather than “to inspire the limitless potential in every girl” as Mattel claims to do with Barbie.[7]

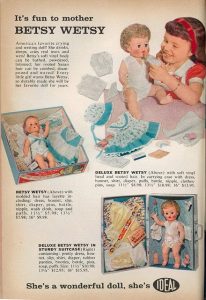

Similar to the way toys that simulate housework convey the expectation that women are intended for taking care of the home, babydolls portray the expectation of a woman as also taking care of children. Take the Betsy Wetsy doll by Ideal that M. G. Lord refers to as “clinging, dependent.”[8] One television commercial for Betsy Wetsy opens with a little girl thinking to herself, “When I grow up, I want to be a mommy.” Luckily for her, she “can play mommy right now, with Ideal’s Betsy Wetsy.”[9] This advertisement clearly states that the ideal life a little girl should imagine for herself is that of a mother. With countless other babydolls filling toy store shelves, Betsy Wetsy was only a small piece of this expectation-setting. With the way domestic toys and babydolls portrayed the capabilities and goals of women, it is easy to see where Barbie could swoop in and be the more ambitious alternative.

I certainly fell into the idea of “girls’ toys” and “boys’ toys” growing up. But growing up with a little sister meant pulling my weight in the playhouse and leaving time for the Power Rangers and Polly Pocket to have a picnic after saving the world. It is only now at 21 years old that I have really tried to understand what some of our toys could represent or teach us. Looking at toy vacuums and babydolls as potentially at odds with Barbie dolls instead of all under the umbrella of “girls’ toys” is a new critical lens that I don’t think I could now ignore if I tried. For what it’s worth, my sister, who played with all of these types of toys, is now an aspiring artist that cooks and cleans for herself and does not dote on any freeloading men.

[1] https://barbie.mattel.com/en-us/about/role-models.html (also follow this link for first Barbie Role Models image)

[2] M. G. Lord, Forever Barbie: The Unauthorized Biography of a Real Doll (Fredericton, N.B.: Goose Lane Editions, 2004), 9.

[3] Ibid., 9.

[4] Ibid., 10.

[5] Sweet, Elizabeth. “Toys Are More Divided by Gender Now Than They Were 50 Years Ago.” The Atlantic. December 09, 2014. Accessed March 29, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/12/toys-are-more-divided-by-gender-now-than-they-were-50-years-ago/383556/. (also see this source for first Sears ad, 1925)

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://barbie.mattel.com/en-us/about/about-barbie.html

[8] M. G. Lord, Forever Barbie: The Unauthorized Biography of a Real Doll (Fredericton, N.B.: Goose Lane Editions, 2004), 9.

[9] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6R9iUdk3EYs

it, I found myself thinking about not so much what Barbie represents (maybe due to my lack of personal connection), but material culture as a whole and how it applies to me personally. A couple of my classmates and myself discussed some of the things we collect when talking about this. I shared that I collect records. While this is true, I failed to fully recognize that I collect something more obvious and apparent.

it, I found myself thinking about not so much what Barbie represents (maybe due to my lack of personal connection), but material culture as a whole and how it applies to me personally. A couple of my classmates and myself discussed some of the things we collect when talking about this. I shared that I collect records. While this is true, I failed to fully recognize that I collect something more obvious and apparent.

careers since her creation in 1959, in addition to spending considerable amounts of time in her Dream House, cruising around in her Glam Convertible, and swimming under the sea as a mermaid. To celebrate her 125th career in 2010, Mattel offered Barbie fans a chance to vote on what career they wanted to see Barbie have next! The choices were “architect, computer engineer, environmentalist, news anchor or surgeon,” and computer engineer came out on top (Gaudin).

careers since her creation in 1959, in addition to spending considerable amounts of time in her Dream House, cruising around in her Glam Convertible, and swimming under the sea as a mermaid. To celebrate her 125th career in 2010, Mattel offered Barbie fans a chance to vote on what career they wanted to see Barbie have next! The choices were “architect, computer engineer, environmentalist, news anchor or surgeon,” and computer engineer came out on top (Gaudin).

Barbie: I Can Be A Computer Engineer. It didn’t take long after the release of CE Barbie for the backlash to begin. And the blessed people of The Internet took it upon themselves to “fix” CE Barbie. Thus, The Greatest Barbie To Exist That Doesn’t Really Exist was born – Feminist Hacker Barbie.

Barbie: I Can Be A Computer Engineer. It didn’t take long after the release of CE Barbie for the backlash to begin. And the blessed people of The Internet took it upon themselves to “fix” CE Barbie. Thus, The Greatest Barbie To Exist That Doesn’t Really Exist was born – Feminist Hacker Barbie.

at coding, so, in the end, she just quit.

at coding, so, in the end, she just quit.