By SaraGrace Stefan

Starting the Climb: An Introduction to Computational Text Analysis

My past two summers have been filled with the stuff of schoolchildren’s nightmares and literary nerds’ dreams: a mountain’s worth of hundreds of books, all requiring digitization, curation, and analysis.

Fortunately, as a PhD student in Temple’s English department, being surrounded by and rapidly devouring books is an ideal way for me to spend the months of June-August. However, those of you who are familiar with the process of book-reading and the traditionally ceaseless marching of time may say, “But wait, SaraGrace, summer vacation is only so long! How could you possibly read hundreds of books?” To that, I would say, “certainly not with that attitude!” and then I would introduce you to distant reading and corpora creation.

Then I would tell you about TWO exciting projects here at the Scholars Studio, one all about Science Fiction and one about Banned Books. Of course, you would be curious to learn more about the current Banned Books project so you’d be thrilled to kindly read my blog post, and follow it with recent graduate Sydney Grimm’s blog post “How to Judge a (Banned) Book by Its Cover: Part 2 of the Banned Books Project” about creating a banned book cover methodology, and read about our initial results and what happens when you judge a book by its cover in Abigail Corcelli’s post “Pulling Back the Curtain on Censorship: Part 3 of The Banned Books Project.”

Gaining a New Perspective: “Distant” Reading and the Cli-Fi Project

But before I get ahead of myself even more, let me define some terms: “Distant” reading is the practice of applying computational methods to a large number of texts, called a corpus, to see what can be revealed by reading and analyzing not just 2-3 books, but 2-3 hundred or thousand. The practice is often associated with the influential and problematic scholar Franco Moretti who coined the term ‘distant reading’, but such methods and their implications have been taken up by a range of academics for diverse purposes, such as Ted Underwood, Kenton Ramsby, and Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein.

Ideally, scholars combine this “zoomed out” perspective with critical research and analysis, so we should not think of distant reading as any sort of replacement for the traditional method of close reading one text at a time. Rather, it provides a different perspective from which we can consider literary and cultural trends.

The Cli-Fi Project

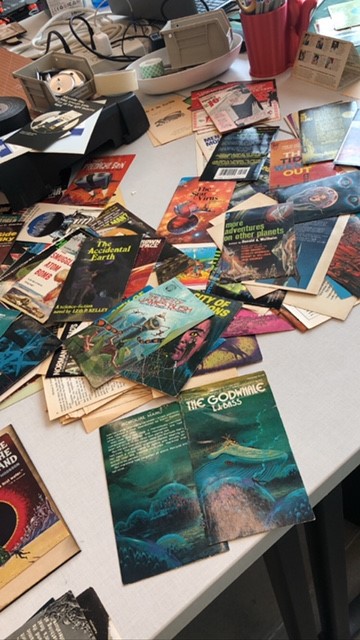

I first gained distant reading experience working on the Cli-Fi Project over the summer of 2022 at the Temple University Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio through funding from Temple’s Arts and Humanities Research Grant. Initially introduced by Dr. Alex Wermer-Colan in his blog posts “Building a New Wave Science Fiction Corpus,” and “Modeling the New Wave: On Learning to Use Machines to Read Sci-Fi Lit,” the SF Digitization project consisted of digitizing and analyzing works of New Wave science fiction to explore how these literary works reflect the largely 20th century concern that humanity’s missteps will culminate in an environmental apocalypse.

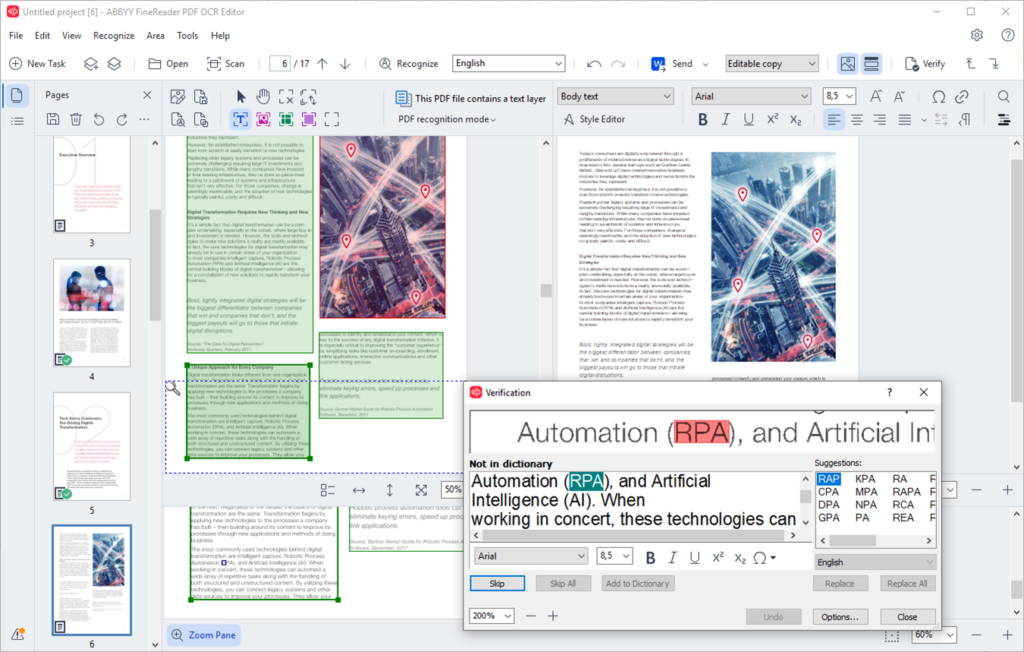

To analyze our New Wave corpus, I joined fellow PhD student Megan Kane, and undergraduate student Asher Riley to pick up where previous students had left off in the digitization and curation process, with a focus on climate-themed science fiction from the Paskow Science Fiction Collection. Temple University librarians had already disbanded, scanned, and stored the texts in a secure server, so it was our job to use an optical character recognition (OCR) software called ABBYY FineReader to “clean” the texts.

The process of improving the OCR output required removing any “unnecessary” information, such as page numbers, the author’s name, etc., as well as correcting the scans to ensure that ABBYY had “read” the books correctly and produced accurate text files.

Once we cleaned and corrected the texts, we were able to transform them into data that we could explore and share with scholars both at Temple University and beyond.

Old Methods, New Texts: The Banned Books Project

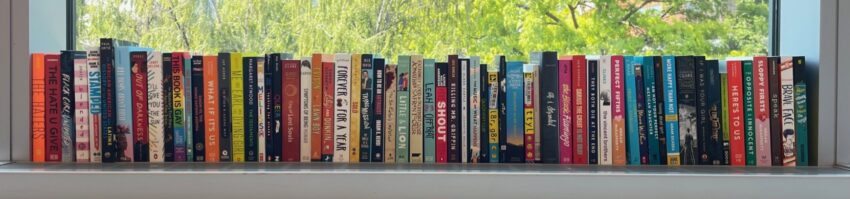

This process of digitizing, correcting, and analyzing literary texts en masse prepared me for the second text analysis project developed out of the Scholars Studio, the Banned Books Project in 2023-2024. Funded by a Mellon grant and led by Dr. Wermer-Colan and the English Department’s Dr. Laura McGrath, we formed a team of undergraduate and graduate students that worked to curate a Banned Books corpus based off of PEN America’s research on which texts have been and continue to be banned in schools and libraries across the United States.

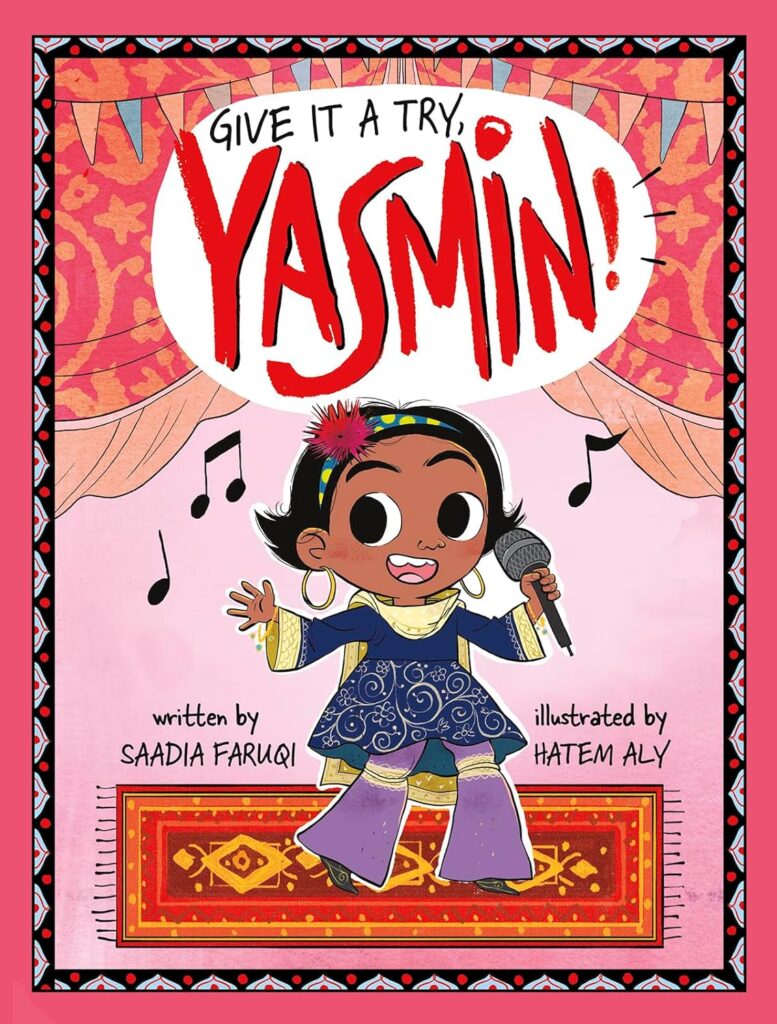

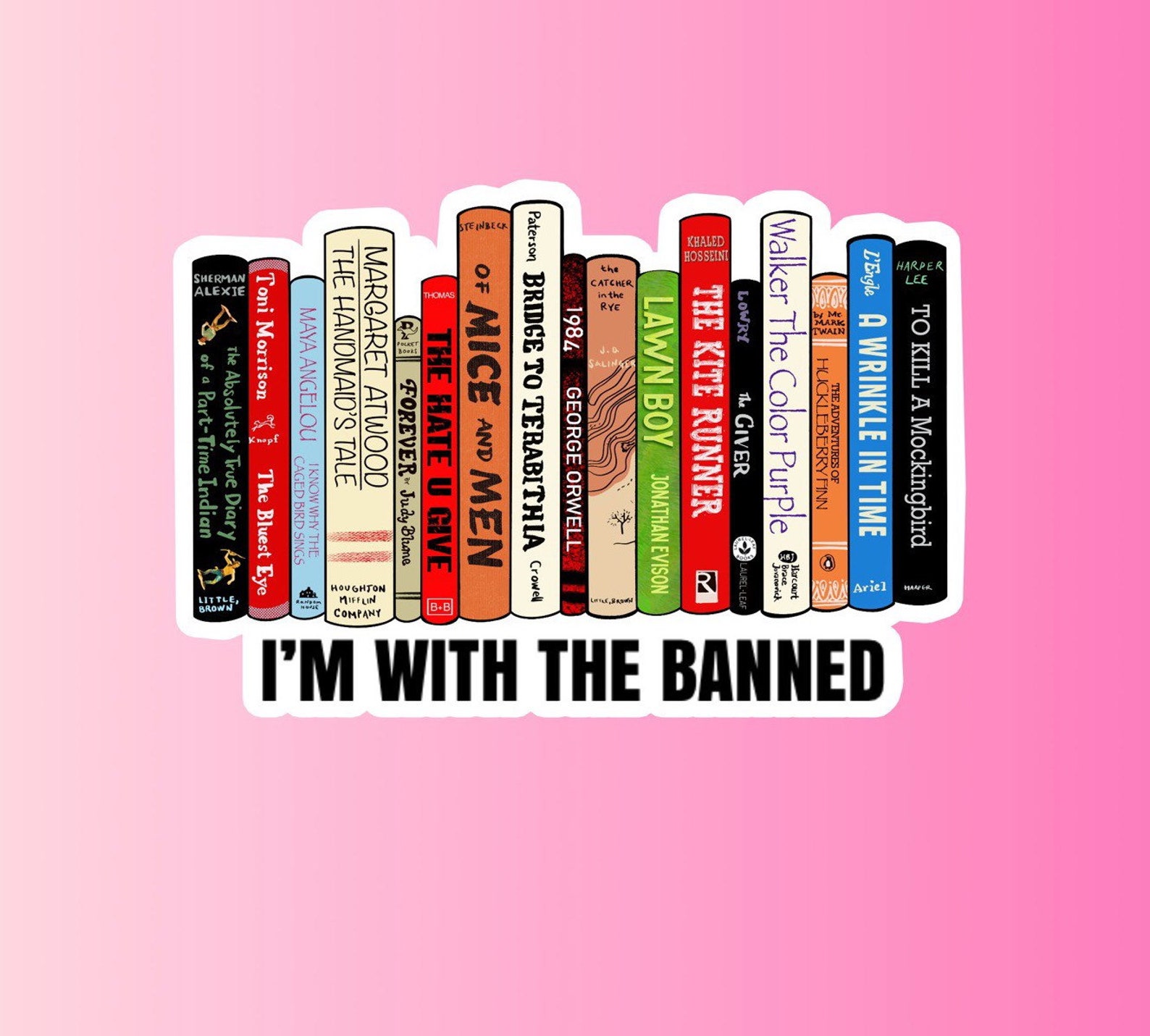

PEN America is a nonprofit organization that advocates for rights-related issues within the literary world. The banned books they identified in their Index of School Book Bans from July 2022-December 2022 range from children’s picture books that depict diverse cultural identities to Young Adult novels that grapple with topics related to sexual exploration, racism, domestic violence, or police brutality. Specific examples include Saadia Faruqi’s Give it a Try, Yasmin (2021), part of a series that features a Pakistani American second-grader and her multi-generational family, as well as Benjamin Alire Sáenz’s Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe (2012) and Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give (2017).

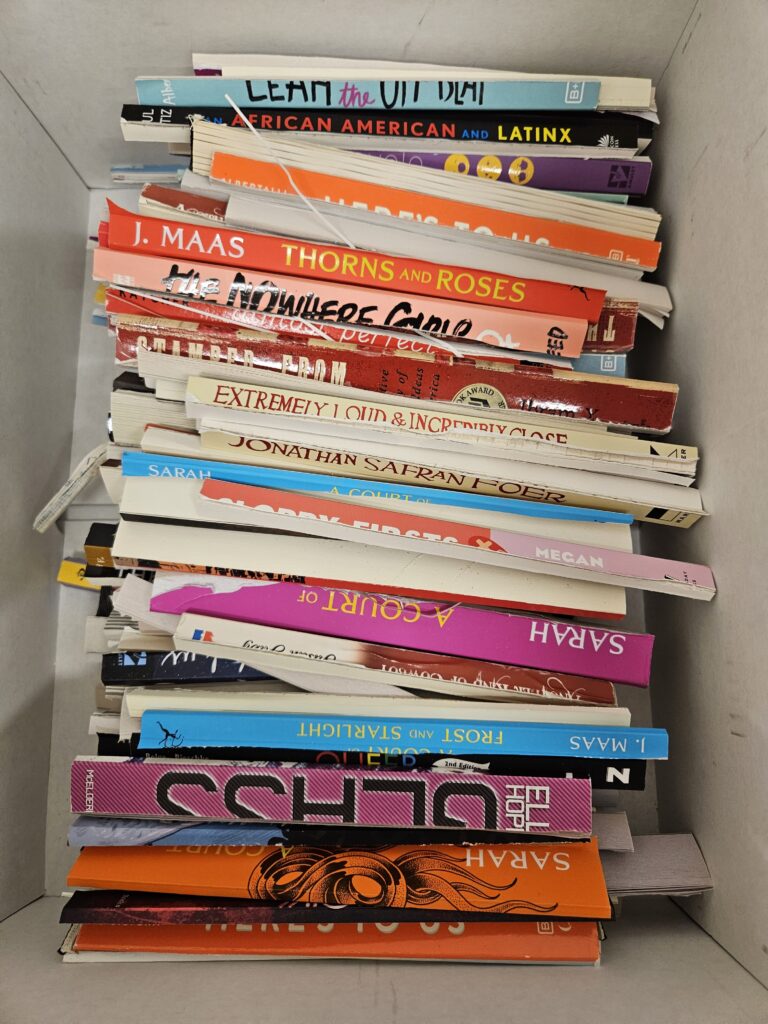

PEN America’s research data (linked above) consisted of the titles of these books and relevant information regarding their bans, such as the location of the school district or the type of ban (being banned from a class vs. being banned from a library, for example). With this dataset, we began the process of selecting and purchasing books to build our corpus. We bought hundreds of physical books for the library’s digitization team to break down into pages that could be scanned. We also purchased digital books through Kobo that could be transformed into machine-readable text files in accordance with a recent exemption to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act enabling scholars to transform eBooks for the purposes of conducting non-consumptive research on copyrighted literature.

As we built our corpus, undergraduate researchers Kriti Baru, Abigail Corcelli, and Sydney Grimm became interested in the appearances of the books that were being repeatedly banned. Our research question honed in on what can be gleaned from these texts if we take on the role of someone attempting to judge the books by their covers alone. If we consider the appearances of the books being repeatedly banned, what might be revealed?

Like I explained in my introduction, you can hear more about the specific methodology for this part of our project in recent graduate Sydney Grimm’s blog post “How to Judge a (Banned) Book by Its Cover: Part 2 of the Banned Books Project” about creating a banned book cover methodology, and read about our initial results and what happens when you judge a book by its cover in Abigail Corcelli’s post “Pulling Back the Curtain on Censorship: Part 3 of The Banned Books Project.”

Conclusions

To wrap things up, these distant reading projects at the Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio have allowed us to interrogate two drastically different “genres” through digital methods: first the Cli-Fi corpus and now the Banned Book corpus. We have not only come to better understand literature and the way it both reflects and acts upon society, but have prepared a valuable dataset for scholars and students alike to interpret the presence of forces actively working to silence marginalized voices and limit representations of cultural, racial, or gender diversity.

We are currently readying our data for future publication, so please contact the Scholars Studio if you would like to utilize our findings for your own research. It is our hope that future scholars can utilize our datasets for exploring questions such as if there is specific language that correlates with books being banned, or how these banned books might compare with a more general corpus.

By exploring these texts and interrogating the banned book phenomenon in the U.S., we can intelligently advocate for the value in and importance of telling these stories, and let those who may support the totalitarian banning of books know that we are “with the banned.”

References

D’Ignazio, C. and L. F. Klein (2020). Data Feminism. MIT Press. https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu/

Klein, L.F. (2018). “Distant Reading After Moretti.” Stanford Humanities Center. https://shc.stanford.edu/arcade/interventions/distant-reading-after-moretti.

Moretti, F. (2000). Conjectures on World Literature. New Left Review, 1, 54. http://libproxy.temple.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/conjectures-on-world-literature/docview/1301903612/se-2

Rambsy, K. (2016). Text-Mining Short Fiction by Zora Neale Hurston and Richard Wright using Voyant Tools. CLA Journal, 59(3), 251–258. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44325917

Underwood, T. (2019). Distant horizons: Digital evidence and literary change. University of Chicago Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/templeuniv-ebooks/detail.action?docID=5524170#

Wermer-Colan, Alex. (2017). Building a New Wave Science Fiction Corpus. Scholars Studio Blog. https://sites.temple.edu/tudsc/2017/12/20/building-new-wave-science-fiction-corpus/

Wermer-Colan, Alex. (2018). Modeling the New Wave: On Learning to Use Machines to Read Sci-Fi Lit. Scholars Studio Blog. https://sites.temple.edu/tudsc/2018/04/26/modeling-the-new-wave-on-learning-to-use-machines-to-read-sci-fi-lit/.