On March 21, 2016, I visited the National Constitution Center’s self-guided women’s history month tour. The focus of the tour is the history of women in the United States, from the struggle for equal rights to women in positions of power. The tour was quite an educational and engaging experience to take part in.

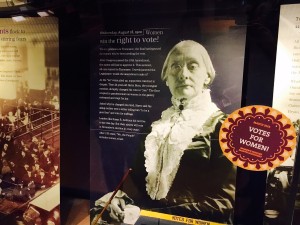

During the month of March, the National Constitution Center offers a women’s history month self-guided tour within the main exhibit called “The Story of We the People.” The focus is on the struggles that women have faced throughout American history, as well as the moments in history when women were successful in their endeavors for equality and justice. The self-guided tour begins at the main exhibit’s entrance with a section to the side of the entrance door where patrons can pick up a pamphlet that explains rather concisely the various content offered in the tour. As you walk through the doors into the main exhibit, the lights are dimmed, and the content is to the side of the room, moving in a circle. The theme appears to be expanding the freedom, focusing mainly on the creation of the United States Constitution and the decades after, as well as the obstacles Americans have faced in the name of freedom. The women’s history content is incorporated into this main exhibit, the stories and objects already on display. To guide the patron and to signal which sections are part of the women’s history self-guided tour, the museum has used rather large stickers placed on the glass cases. The women’s history tour begins farther in within the main tour, with the first woman displayed being Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Throughout, the main focus of the self-guided tour is on women’s struggle for equality, suffrage, civil-rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, and ending with a display that focuses on Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, with her judicial robe being the main focus. Numerous letters are also on display, one being the letter that Ida B. Wells wrote to address the violence taking place in the southern states. Throughout the tour, there are also touchscreens where patrons can watch and listen, with a device similar to a receiver, to some of the most influential speeches in women’s history. Aside from the content on women’s history displayed to the side of the room, there is also a “national tree of faces,” where patrons can touch a screen and learn about numerous women in history.

During the month of March, the National Constitution Center offers a women’s history month self-guided tour within the main exhibit called “The Story of We the People.” The focus is on the struggles that women have faced throughout American history, as well as the moments in history when women were successful in their endeavors for equality and justice. The self-guided tour begins at the main exhibit’s entrance with a section to the side of the entrance door where patrons can pick up a pamphlet that explains rather concisely the various content offered in the tour. As you walk through the doors into the main exhibit, the lights are dimmed, and the content is to the side of the room, moving in a circle. The theme appears to be expanding the freedom, focusing mainly on the creation of the United States Constitution and the decades after, as well as the obstacles Americans have faced in the name of freedom. The women’s history content is incorporated into this main exhibit, the stories and objects already on display. To guide the patron and to signal which sections are part of the women’s history self-guided tour, the museum has used rather large stickers placed on the glass cases. The women’s history tour begins farther in within the main tour, with the first woman displayed being Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Throughout, the main focus of the self-guided tour is on women’s struggle for equality, suffrage, civil-rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, and ending with a display that focuses on Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, with her judicial robe being the main focus. Numerous letters are also on display, one being the letter that Ida B. Wells wrote to address the violence taking place in the southern states. Throughout the tour, there are also touchscreens where patrons can watch and listen, with a device similar to a receiver, to some of the most influential speeches in women’s history. Aside from the content on women’s history displayed to the side of the room, there is also a “national tree of faces,” where patrons can touch a screen and learn about numerous women in history.

The self-guided tour, though rather brief, displays some of the most well-known women in the history of U.S. suffrage, civil rights, and equal rights. Beginning with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the tour contains information on the Convention in Seneca Falls. This section addresses Cady’s role in empowering women to make their voices heard, as well as to address women’s rights. This section was rather short; although, the incorporation of Seneca Falls with the next display adds strength to the tour. Having read numerous articles focusing on Seneca Falls and women’s rights, these articles give clarity to this concise section of the tour. As much of the tour focuses mostly on women’s early fight for certain rights, including the right to vote, the incorporation of both Susan B. Anthony and Ida B. Wells designates these two women as the tour’s women of the suffrage movement, yet Anthony is the woman that many people tend to see and hear about when learning about the women’s suffrage movement, so the display featuring Ida. B. Wells is quite refreshing. Ida B. Wels is also displayed within the exhibit as a woman who advocated for civil rights. Although together, the content is displayed in chronological order with the main exhibit’s content, which adds more depth to the displays but also took away from the idea of a women’s history focused tour. Aside from this, the section of the tour covering Ida B. Wells includes a paragraph detailing her story of being a passenger on a train and being violently forced out of the train car by a white male employee. 1 This story ties in with both the course content and specifically with Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham’s “African-American History and the Metalanguage of Race.” Having already read Higginbotham’s article, which details Ida B. Wells’s ordeal in-depth, the museum takes great strides in re-creating Well’s experience to the patron. The story also shows that Wells was an advocate and a woman who struggled to overcome injustice. A letter that she wrote is displayed in the glass case, which was written as an effort to expose the injustice and violence African-American men and women were facing in the South. On display some inches away from the glass case focusing on Wells is a display case dedicated to the women who struggled to organize protests, while also focusing on the proposal for the Equal Rights Amendment. It was nice to hear about the stories of these women, especially when much of the tour focuses on both many of the events and women that we typically encounter at museums showcasing women throughout history. The tour progresses through decades of women’s history, ending with Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s story of serving on the Supreme Court. This section of the display shows another side to the tour, a side that focuses on a woman in a position of power.

Surprisingly, many of the employees at the National Constitution Center were unaware of the women’s history month self-guided tour. It also took me some time to figure out where the tour began, as I would soon realize that the self-guided tour was actually a tour of the regular exhibit that just incorporates some events in women’s history throughout. I was also surprised at how little the event was advertised, as well as how few patrons were taking the self-guided tour. Aside from this, I would prefer there to be more cohesion in the tour; sections of the tour are spread around the room. What has left me with the most questions is why some women and events were designated as part of the tour, while others were left out. It appears that the content is a regular part of the museum; the self-guided tour for women’s history month just involves the addition of stickers to guide patrons to specific display cases, but I felt that a section that focuses on prohibition and the women involved with prohibition would be interesting to add to the tour. I also question why they left out the shirtwaist factory strikes when displaying women who protested. 2 Other than the how brief the tour remains, the tour gives patrons a chance to witness the accomplishments of women throughout United States history. The inclusion of the tour within the main exhibit also allows the content to be seen by patrons who may not have visited the museum because of the women’s history tour but otherwise are able to still take part.

The women’s history month self-guided tour at the National Constitution Center provides an interesting experience, while including a lot of information within a rather brief tour. While I may have liked to have gone through a tour separate from the main exhibit, the main tour put the women’s history self-guided tour into more of a historical context, just as numerous articles read in class and Higginbotham’s article did for the women’s history tour content. Overall, the tour was a nice experience and a clever way to incorporate women’s history month inside of such a well-known United States history museum.

Notes

1 Evelyn B. Higginbotham, “African-american Women’s History and the Metalanguage

of Race”. Signs 17, no. 2. (1992): 251–74. Accessed March 31, 2016.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174464.

2 Daniel, Sidorick. “The “Girl Army”: The Philadelphia Shirtwaist Strike of 1909-1910.”

Pennsylvania History 17, no. 3. (2004): 323-369. Accessed March 31, 2016.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/27778620