By Marilla Cubberley

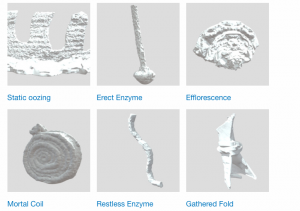

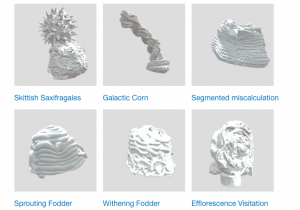

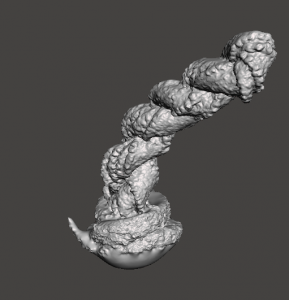

In my last blog post, I wrote about incorporating the technology at the Scholar’s Studio into my art practice and my goal of making 100 objects with both digital and physical iterations. I learned how to make 3D scans of my objects using the EinScan Pro 2X and how to put the scans into the 3D modeling programs Meshmixer and Blender. Some objects I left as is, and some I manipulated, multiplying, combining, and stretching objects.

My original, physical, small sculptural objects are made with a combination of found and made materials, mixing plastic bread tags and Sculpey or knitted yarn with rubber bands. Through digitization, my collection of 100 objects become “speculative” because they can exist in endless forms, through being downloaded, manipulated and printed by anyone who might come across them on the internet.

In this blog post I am thinking through several questions. What is a speculative object? How do I communicate that it is a speculative object? And finally, why make a speculative object collection?

Speculative Fiction and Thing Theory

My interest in the speculative originates from my love of science fiction and its ability to disrupt our understanding of our perceived reality. The two books that I return to again and again are Octavia Butler’s Dawn (1997) and Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (1974). I influenced by Christina Kiaer’s essay on Boris Aratov’s Everyday Life and the culture of the Thing (1925) Aratov was a Russian Artist and Critic in the Constructivist movement. Kiaer’s essay Boris Aratov’s Socialist Object (1997) contextualizes Aratov’s theories and asks us to consider our social relations to everyday objects and disrupts the perceived naturalness of them. I will return to this later on.

In Le Guin’s essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” (1986), she explores how the unobserved can be uncovered by science fiction.

“If science fiction is the mythology of modern technology, then its myth is tragic. “Technology,” or “modern science” (using the words as they are usually used, in an unexamined shorthand standing for the “hard” sciences and high technology founded upon continuous economic growth), is a heroic undertaking… If, however, one avoids the linear, progressive, Time’s-(killing)-arrow mode of the Techno-Heroic, and redefines technology and science as primarily cultural carrier bag rather than weapon of domination, one pleasant side effect is that science fiction can be seen as a far less rigid, narrow field, not necessarily Promethean or apocalyptic at all, and in fact less mythological genre than a realistic one.

It is a strange realism, but it is a strange reality” (Le Guin, 1).

Le Guin’s description of Science Fiction offers a useful framing for my collection of objects and how I’m thinking about the speculative.

Speculative Objects and Archival Practices

Through this project I seek to avoid the linear and the rigid, instead favoring the soft and flexible. It is a rejection of rigidity and a rejection of linear growth; an attempt to look backwards and forward simultaneously. How can an object embody these attributes?

There are two ways that I explore this idea: first, I aim to make an object that can shift and change and remain slippery; second, I’m thinking about the relationship between my objects and others that encounter them.

In Christina Kiaer’s article “Boris Aratov’s Socialist Object” (1997), Kiaer contextualizes Aratov’s theory and gives us some key points: “This object “connected like a co-worker with human practice,“ will produce new relations of consumption, new experiences of everyday life, and new Human subjects of modernity” (Kiaer, 2).

Inspired by this description, I have begun making objects that can be redefined endlessly and whose ownership can be questioned. This is very idealistic of Aratov, but an ideal I find worthwhile to pursue. How can we produce new social relations through art making? Or more accurately is it possible?

“Aratov states in a key passage that even the most mundane, low-tech everyday objects engender culture. ‘The ability to pick up a cigarette-case, to smoke a cigarette, to put on an overcoat, to wear a cap, to open a door, all of these ‘trivialities’ acquire their qualification, their not unimportant culture’” (Kiaer, 3).

Web Archives for Speculative 3D Models

I am in the process of building an online archive to host my 100 digital objects using Omeka. A free open source web-publishing platform, Omeka was created specifically as a tool for Libraries and Museums to host digital collections and exhibitions.

In my Omeka collection, each 3D model is linked to its Sketchfab page, where anyone can download my 3D models for free. My use of Omeka is important in that Omeka is an open source platform, but also that it is designed to exhibit collections for cultural institutions. It is used to exhibit cultural heritage collections that previously would only be available to view in physical form.

Through creating a speculative collection, I am examining my relationship to the object and to the viewer or audience. When presented with an object, what is our relationship to that object? What do we believe about it? Where do we place it?

My Omeka site has a physical counterpart in the form of sculptural holders. Each holder has several platforms where my Objects can be placed. This is supposed to evoke a feeling of impermanence as I can shift and change which objects are being displayed.

Having a digital collection is crucial to my exploration of the speculative. With the use of 3D scanning and modeling comes the ability to reproduce my objects endlessly. They can be downloaded and remain as a file, or they can be printed creating several permutations of the same object. This shift is distinct from the shifting of the 3D model in a 3D modeling program. Where it shifts its shape, not its material.

The social relations around these objects can be ever shifting, as the objects themselves are shifting and changing.

Collecting Mundane Things

Investment in the mundane is crucial to my project. My objects are constructed off of a personal collection. What do I see? What do I collect? I collect rocks and plastic and trash. Why do I collect?

Returning to Le Guin’s “Carrier Bag Theory,” she discusses the act of collecting:

“If it is a human thing to do to put something you want, because it’s useful, edible, or beautiful, into a bag, or a basket, or a bit of rolled bark or leaf, or a net woven of your own hair, or what have you, and then take it home with you, home being another, larger kind of pouch or bag, a container for people, and then later on you take it out and eat it or share it or store it up for winter in a solider container or put it in the medicine bundle or the shrine or the museum, the holy place, the area that contains what is sacred, and then next day you probably do much the same again — if to do that is human, if that’s what it takes, then I am a human being after all. Fully, freely, gladly, for the first time” (Le Guin, 4).

This human activity is also an investment in the mundane. Many of these objects that she describes could fall into the category of a socialist object, depending on the social relations around them. The potential to question and rethink social relations is what makes something speculative. These objects alongside the collecting and distribution of them is speculative because it requires an examination of the relations of an art object to the world around it.

Conclusion

You can find my Objects on my Omeka site Collected Objects. I’m collecting found and made objects in various combinations. Some of them are recognizable, some of them are harder to place, but the through-line is that I have put them all together and am presenting them to the viewer. Through the digitization of this collection, I aim to poke holes in how we view objects, and how they shape our reality.

References

- Le Guin, Ursula, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” in Dancing at the Edge of the World (New York: Grove Atlantic Press, 1989)

- Kiaer, Christina. “Boris Arvatov’s Socialist Objects.” October, vol. 81, 1997, pp. 105–118. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/779021. Accessed 3 Mar. 2021.

- Kiaer, Christina. “Boris Arvatov’s Socialist Objects.” October, vol. 81, 1997, pp. 105–118. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/779021. Accessed 3 Mar. 2021.

- Le Guin, Ursula, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” in Dancing at the Edge of the World (New York: Grove Atlantic Press, 1989)