By Marilla Cubberley

Introduction

As a graduate fellow at the Scholars Studio, I began the semester interested in researching how the digital sphere changes the way I make and conceive of “art objects.” I am a second year MFA candidate in the Fiber and Material studies program at Tyler School of Art who easily feels lost when it comes to digital scholarship, like stepping into an unknown world of technology.

Typically I enjoy working and making with my hands. The thing that draws me in when making is the process rather than the end result. I collaborate with my materials through a visual and tactile language. I use both found and non-found materials to make objects that I have manipulated by use of knitting, sewing, glueing, molding and welding.

Making in Physical and Digital Worlds

I started the semester with the seemingly straightforward (to me) goal of making 100 objects with both digital and physical iterations. This, of course, turned out to not be as straightforward of a task. Learning how to 3D scan, model, and print has taken me in many different directions. I did not consider how many variations of a single object could be created through these processes. I have the original physical object, the digital model, the 3D printed form, but within and between these three categories, there is endless potential for various combinations and permutations.

How do these processes change the mythology of the objects I’m making? How did it come to exist and what is its function now that it does? When I start to make something, improvisation and chance are involved.

Learning to 3D Scan

While working this fall at the Scholars Studio, I have immersed myself in digital software. In order to learn the prerequisite tools to begin making art, with little to no prior knowledge of 3D scanning and modeling, I needed a lot of time and help to reach a point of experimentation.

The first thing I learned to use in the Scholars Studio was the EinScan Pro 2X Plus to create 3D scans of my objects. I discovered that scanning the objects is a slow methodical process. You must be sure that every angle is captured and oriented correctly. David Ross, the Makerspace Manager, helped me immensely to understand the ins and outs of this incredible machine.

What is essentially happening when using this scanner is that it is creating a point cloud from each scan. I put my object on a lazy susan and slowly turn the object so that the scanner picks up every crevice and protuberance. If the object one is attempting to scan is too symmetrical and smooth it will be virtually impossible to get a usable scan because the software will not know how to orient itself. On the flip side, if your object is too chaotic (like a tiny abstract sculpture) with lots of points that are vaguely similar, the scanner will not know how to orient itself.

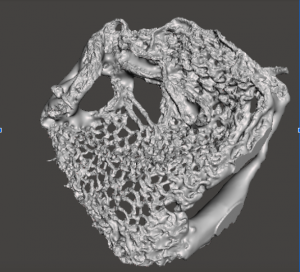

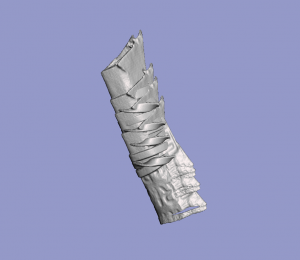

This is an example of an object that was particularly challenging to scan. The original object is a small knit structure hardened and shaped with Elmer’s glue. When knitting something you are essentially creating rows of loops that interlock to create singular mass. Each loop in a row of a knitted object is referred to as a “stitch”. As the scanner tries to identify each knit it occasionally has difficulty distinguishing stitches adjacent to each other. To capture the 3D model required numerous readjustments. Once I have a scan that I’m happy with, the EinScan Pro 2X creates a watertight mesh from the point cloud that can be exported as several file options. For my purposes, the best option is an .obj or .stl file which can go straight into 3D modeling programs.

Learning to 3D Model

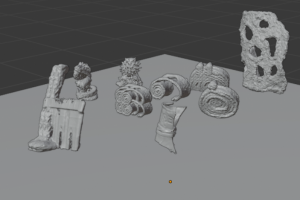

The two 3D modeling programs I have been spending most of my time with are Blender and Meshmixer. Meshmixer is a great tool for learning the basics of 3D modeling and set me up to begin to understand the much more complicated world of Blender. I have been using a mixture of both programs to experiment with my objects. Meshmixer makes it easy to multiply and combine my scans.

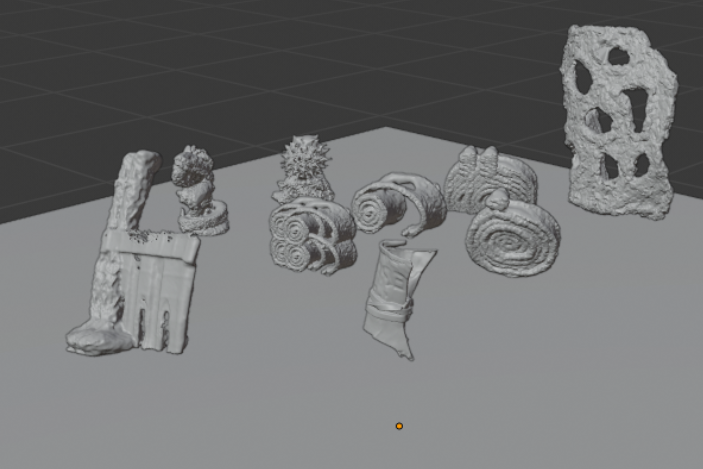

With Blender I have been thinking about how my objects can exist together in a digital space and how I can start adding texture and color to my scans.

As I learn more about the basic operations of these programs I am able to begin improvising. Because Meshmixer is a more simplistic program I am able to work more intuitively. I find so much satisfaction in multiplying, combining and transforming the meshes. The possibilities of manipulation offered by digital platforms allow for experimentations that would be impossible in some cases to achieve in the “real” world. However, I find myself inspired to attempt to manufacture objects by hand that are a result of digital experimentation.

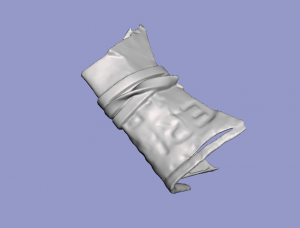

My baseline sequence of production has been to scan my object, prepare my object to be printed. Once my object is ready to be printed I use either the FDM: Prusa MK3 printer or the SLA: Form 3 printer. The first prints in filament and the second prints in resin. Each object takes about 5 to 10 hours to print. As a result I have three iterations from the same object.

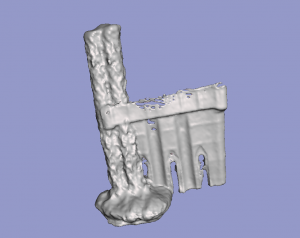

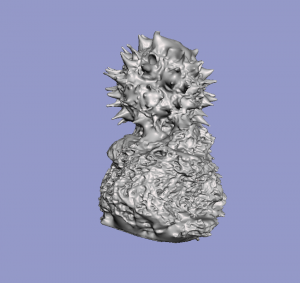

Each of these is its own object, with its own distinct formal traits. The original is made from felt, spray paint, resin and a sweet gum pod. When a mesh is created from it, the parts that the scanner was unable to pick up are smoothed out, creating the smooth sections you can see above on the 3D model. These smooth sections also appear in the resin printed version. This gives the object a distinctly digital look.

I’m in the process of naming and thinking about how I want to communicate their mythology. The literal way that I made them is key in describing their mythology. The next question I must tackle is how do people interact with them?

Creating an Archive of Speculative Objects

My interest in the speculative is drawn from reading a lot of speculative fiction. Primarily, Octavia Butler and Ursula Le Guin. Currently I am trying to figure out if it is possible to make a speculative object. Primarily because I have not figured out how I want the speculative object to define itself. Would it be in the description of the object? Do these objects need to have an invented function? Is it possible to communicate that it is a speculative object without words and just through the object itself?

I plan to continue to investigate these questions as I make my objects. I see 3D modeling as speculative because of its reproducibility and its impermanence. Moving forward I plan to make a digital archive of my 3D models with the web platform, Omeka S. Each model will have a link to an open source downloadable file that could be downloaded and either printed or put into a 3D modeling program.

I’m still at the beginning stages of this idea, but my hope is that this could push the reproducibility and impermanence of these objects. They can exist in endless forms, through being downloaded, manipulated and printed by strangers on the internet.