By Bethany Farrell

On the walk between Temple’s Art History department and Paley Library (where the Digital Scholarship Center is located) there has been a poster pasted to a wall. On it is a Marshall McLuhan quote, “we shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.” Beside the writing is a literal manifestation of this idea—the character of Morty, from the cartoon Rick and Morty, with a hammer for his head. In my most recent blog, I contemplated how DH tools have transformed the way I think and research. The poster got me thinking more broadly about technological developments and the practice of art history.

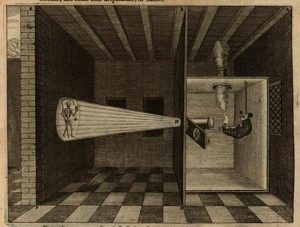

Art history’s flourishing has depended on the development of new imaging technologies. In the late fifteenth and sixteenth century the emergence of prints, in particular reproductive prints, broadened the audience for artworks such as the Sistine Ceiling and Last Supper. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, photography, coupled with the magic lantern and slide projector, provided greater reproductive accuracy allowing scholars to more easily research and teach. Kodachrome film revolutionized art history in the 1930s with the introduction of color images. It was not just the progress towards mimesis in reproductive images that altered the way scholars taught and thought. Heinrich Wölfflin’s pioneering dual projector art history lectures in the early twentieth century profoundly changed the manner in which art was analyzed. Even today, budding art historians are first trained to evaluate objects via comparison—epitomized by the dreaded slide comparison exam question.

The dual slide projector was an enormous stride for art history pedagogy. Yet the technology was ultimately cumbersome. As an undergraduate I witnessed professors or their TAs drag slide carousels across campuses and deal with mid-lecture projector failure. In the early twenty-first century, as mentioned in my previous blog, art historians began to transition to PowerPoint. For the past twenty-ish years, PowerPoint has become the standard tool for lectures. But despite its benefits—it is a very stable, universal application—I find myself uncertain whether it has changed methodologies in art history.

Powerpoint as a pedagogical tool was only possible with the emergence of digital photography. Digital images have certainly changed the discipline. Reproductions of art have increased in accuracy and quality. Macrophotography has allowed scholars to look at the minute brushwork of artists such as Rembrandt, Jan van Eyck, and Monet. Digital images have changed not just how we look but what we look at. Periods of art that were understudied due to bias during the formation of the canon have begun to be evaluated. In my particular period, more art historians are researching the art made between the end of Mannerism and the emergence of the Baroque because of greater image accessibility.

Reproductive prints, photographs, magic lanterns, Kodachrome film, dual slide projectors, and digital images all changed the way we perceived and studied art. The medium has been the message for art history. In the coming years, newer imaging technology such as virtual reality and three-dimensional models will continue to move the reproduction of sculpture and architecture towards mimesis. In addition, platforms such as the Frick’s ARIES (ARt Image Exploration Space) will provide new research tools for art historians. The implementation of DH research and projects have also begun to change the way art historians study. As the tools continue to be developed, they will also shape, as older technologies did, the practice of art history.

Kohl, Allan. “Revisioning Art History: how a century of change in imaging technologies helped to shape a discipline.” 39.1: VRA Bulletin.

https://online.vraweb.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=vrab

Hi everyone, it’s my first visit at this web page, and piece of writing is actually fruitful in support

of me, keep up posting these types of posts.

Very good post! We will be linking to this particularly great content on our site.

Keep up the good writing.