By Emily Logan

Critical Making can be described as “a mode of materially productive engagement that is intended to bridge the gap between creative, physical and conceptual exploration” (Ratto, 252). Coined by a faculty professor at University of Toronto named Matt Ratto, the theoretical term critical making focuses on the process and act of making rather than the physical object itself. As stated by Ratto in his article Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life, “the closest connection is to constructionist forms of learning in that the process of making is as important as the results”. However, it goes beyond constructionist theory, by unraveling social, historical and technological implications of human interactions within the physical/technological world.

Matt Ratto and the Critical Maker Lab

Ratto is the director of the Critical Maker Lab located in Toronto, Canada. The space in many ways resembles that of a makerspace, yet it differentiates itself in that these projects focus on linking object-making to academic research, social phenomenon and theory-based practices. The space has conducted projects that explore critical issues of intellectual property, technological bias, identity and public space. One example of a project at the Critical Maker Lab is a project called Social/Lites from Bruno’s Bellybutton which is described as “an exploration in collaborative dinner theater”. Essentially, this project explores non-verbal communication and social norms through the means of a dinner table performance. Players sit at the table and interact socially with one another per usual, yet the technological components imbedded under the table and inside their wine glasses create subtle social cues that build another dimension to the conversation. Whether the goal of the performance is to stop one person from jabbering on about uninteresting nonsense, or to insight subtle social cues that might have otherwise been subconsciously annoying, this critically-made scenario engages the reader to think about how one communicates without disrupting our culture’s precious social norms. Below is a description of how the experiment works technically.

One example of a project at the Critical Maker Lab is a project called Social/Lites from Bruno’s Bellybutton which is described as “an exploration in collaborative dinner theater”. Essentially, this project explores non-verbal communication and social norms through the means of a dinner table performance. Players sit at the table and interact socially with one another per usual, yet the technological components imbedded under the table and inside their wine glasses create subtle social cues that build another dimension to the conversation. Whether the goal of the performance is to stop one person from jabbering on about uninteresting nonsense, or to insight subtle social cues that might have otherwise been subconsciously annoying, this critically-made scenario engages the reader to think about how one communicates without disrupting our culture’s precious social norms. Below is a description of how the experiment works technically.

“Social/Lites from Bruno’s Bellybutton is a social device that enhances pre-existing communication currents through technology and human social knowledge. It is a simple concept: each place at a table is equipped with a foot pedal attached by wire to a central Arduino hub, which itself is connect to specially constructed glasses at each place. The pedals are able to communicate with each glass by pressure switches within the pedals assigned to each glass at the table. The glasses, in turn are able to both send and receive messages by means of LEDs and mercury switches. When a participant wants to send a message to a particular companion, she activates the corresponding pressure switch in the foot pedal and tilts her glass in one of three predetermined directions. The mercury switches in the glass (separated from the liquid for health reasons) read the direction the glass is tilted and send a message to the intended recipient. Each direction corresponds to one of three commonly known iconic symbols: smiley face, winky face, and frowny face. Thus the sender chooses the recipient with the pedal and the message with the glass. The recipient sees one of three backlit emoticons glowing at the bottom of her glass (emoticons were chosen because of their simplicity and increasing universality). The light is strong enough to make the glass glow, alerting everyone at the table to a message, though they are unaware of what the message is and who sent it.”

To read more about Soical/Lites and other Critical Maker Lab projects click here.

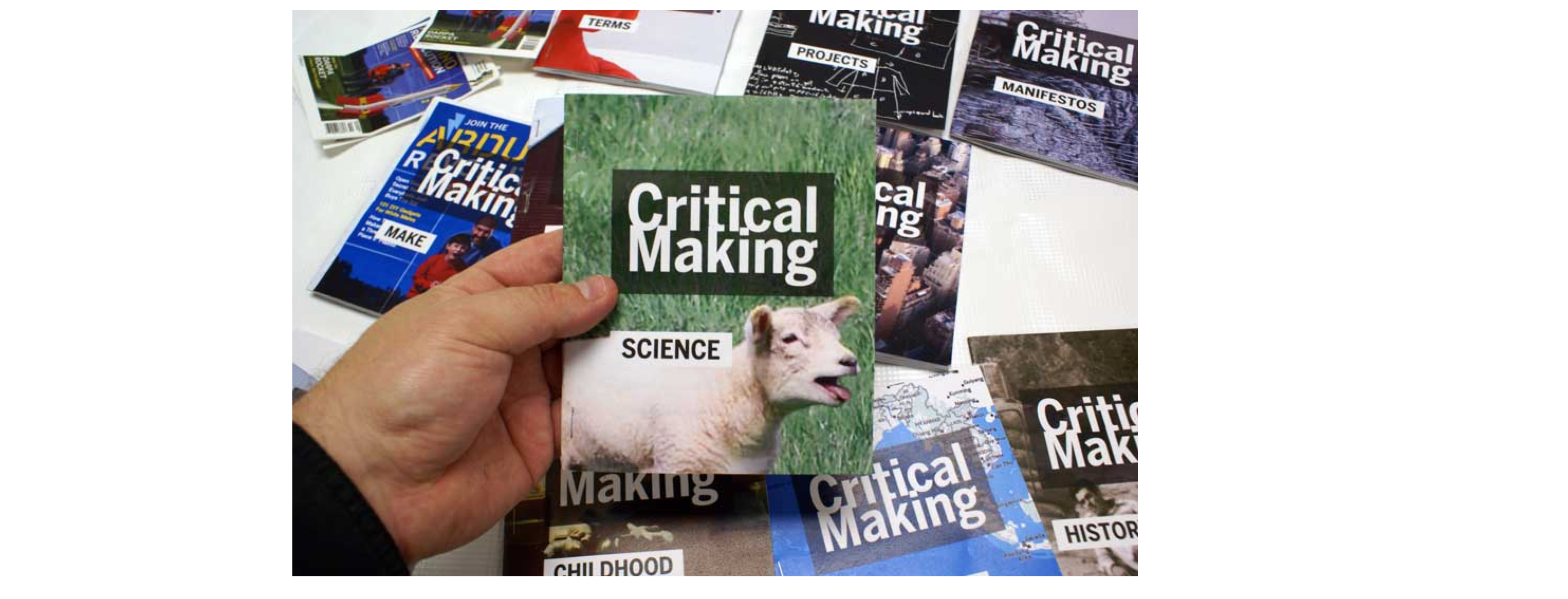

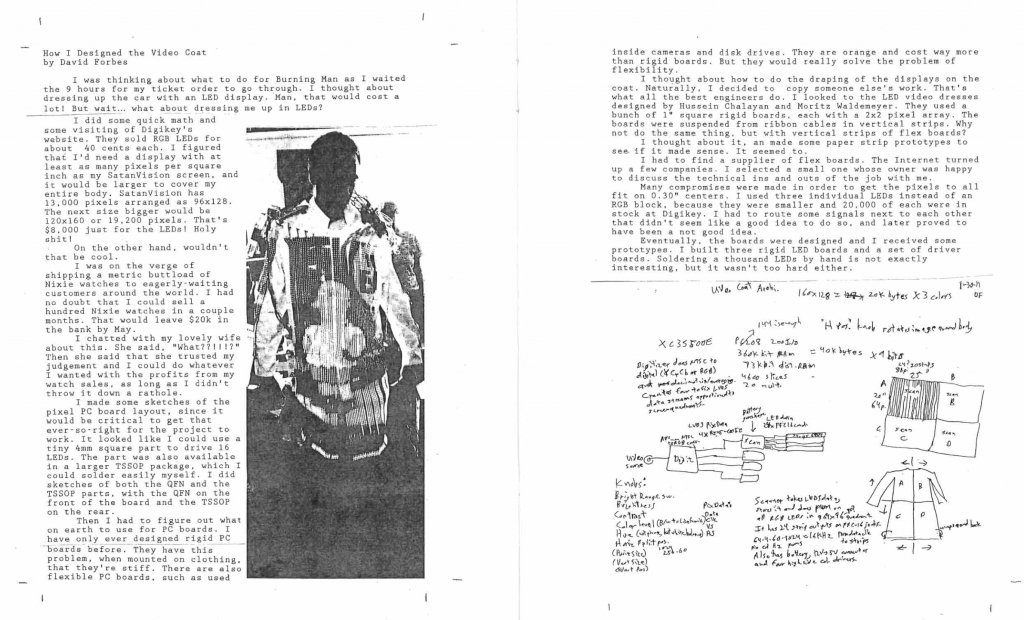

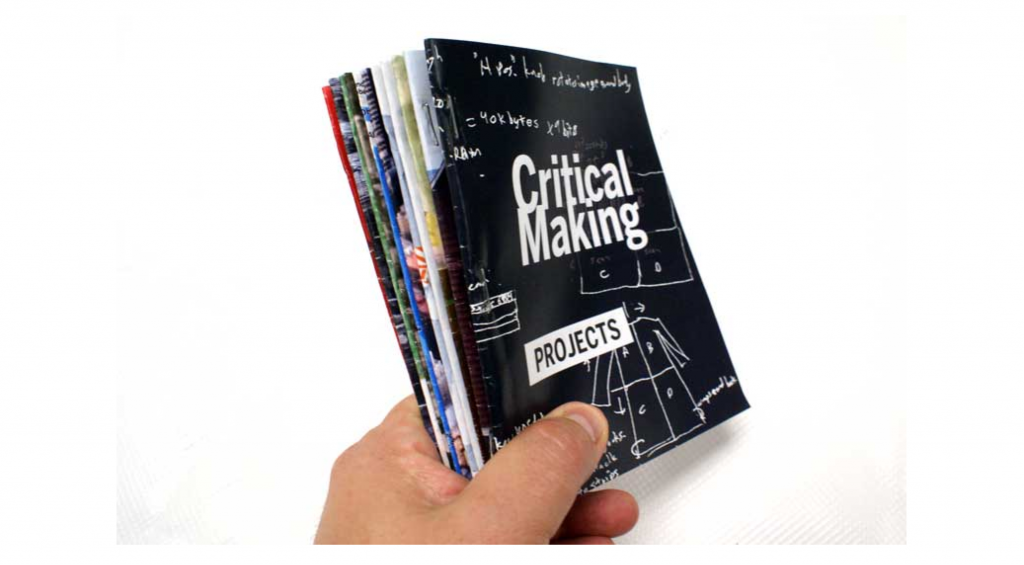

Garnet Hertz and conceptlab Critical Making Zines

Located on the western shore of Canada in Toronto, Emily Carr University is home to a professor of Design and Dynamic Media named Garnet Hertz. He, too, is leading the exploration of similar critical making dialogues through his online research blog called conceptlab. In 2012, Hertz created a series of zines that explore “how hands-on productive work – making – can supplement and extend critical reflection on technology and society”. This project consisted of him creating a collection called Critical Making which consisted of 10 handmade booklets on various categories within the critical making sphere. There were only 300 finished copies printed due to the DIY nature of the entire project (meaning it too a long time to hand bind them all!). The publication houses 70 contributors in total, with the vast majority from the fields of contemporary art and academia.

Due to the spread of interest on the project, the entire collection can be viewed on online here.

The titles of the 10 booklets are as follows:

Intro / / Manifestos / / Terms / / Projects / / Science / / Conversations / / Make / / Places

Open Source / / History / / Students / / Childhood

When the two worlds collide: Garnet Hertz actually had an interview with Matt Ratto in the Conversations Zine. Check out the interview here.

Critical Making and If Gardens Could Talk

Critical making informs the methods and goals of my smart garden device project If Gardens Could Talk part 1 & part 2. The location of the garden is a sensitive social climate in which many constituent players are involved. Race, and social class are at play in the ever-changing landscape at the intersection of 15th and Diamond Street. Government regulations, property borders and questions of ownership and stewardship are also at play. Who is the landowner, and who is the tenant? The community garden space becomes political grounds for change-“making”. If we glance back at Matt Ratto’s definition of physical making, the act of gardening in an urban environment could be the focus, and the plant (physical object or product) may come as secondary importance. Maybe the end result is not just the food grown, but rather, the land in which the growing takes place.

Work Cited

Matt Ratto (2011) Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life, The Information Society, 27:4, 252-260, DOI:10.1080/01972243.2011.583819