Inspired by Hyangeun (Jenny) Ji’s workshop out of the Scholars Studio yesterday on How to Talk with AI: Prompt Engineering, I continued my exploration of how generative AI tools might support my work in data analysis and assessment. Jenny’s lesson #1: The best way to learn about AI is to experiment, and her tips and guidance provided just the motivation to do so.

We need to understand trends in the use of the Charles Library. We see thousands of students come through the door each day. But our knowledge of day, time, and demographics can be anecdotal. We do get weekly gate reports, .csv files that include date, time, college, and student level. In this experiment, I asked ChatGPT to analyze two gate reports from a busy week in February (February 19-25, 2024 and February 20-26, 2023). My starting instructions: “Analyze these two csv files and then I will ask questions of you to compare the data in each.”

ChatGPT proceeds to output a data overview of each file, detailing each column name, such as date, time, academic level and college, and entrance used. It’s rather dry and technical, just raw numbers. But kindly, ChatGPT suggests,

“If you have specific questions or analyses you’d like to perform on these datasets, please let me know! “

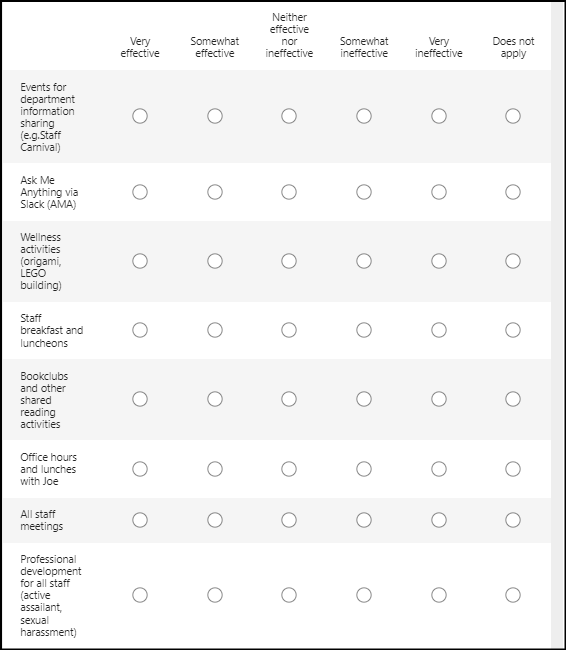

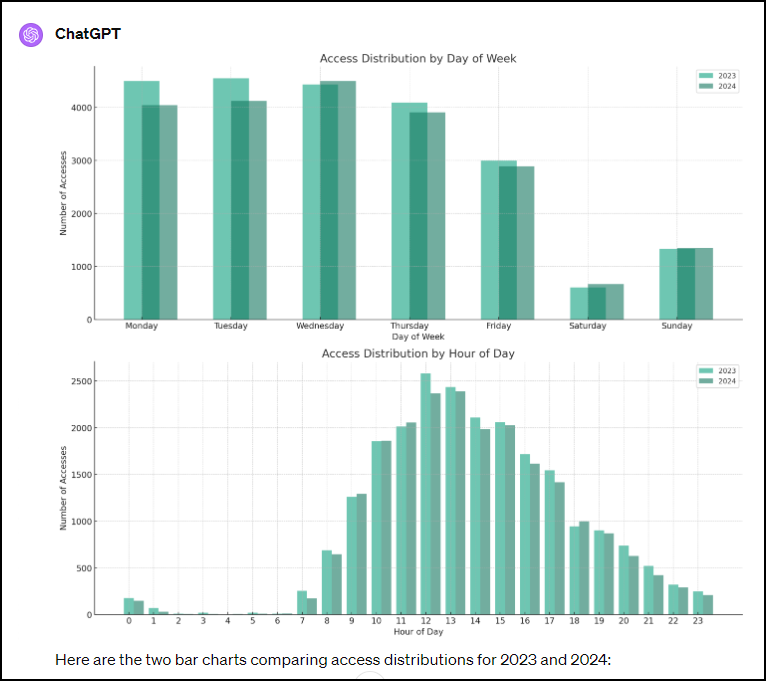

What a nice invitation! I did have some questions. I asked ChatGPT to compare traffic by days of the week, by time of day, and also by college. Since I like visualizations, I asked this data to be shown as a bar graph. ChatGPT complied:

I’m impressed. But the analysis is not perfect. For instance, there is no school of Theology at Temple, nor is there a Creative Arts school. Chat GPT is using a two-letter code and predicting what that might stand for. But still…

Chat GPT as Consultant

What would it look like to have an external data “consultant” review this data and provide their perspective? I asked ChatGPT to take on the consultant “persona” and provide me, an academic library administrator, with some insights. Here’s the result:

- Resource Allocation:

The clear peak usage times around midday (10 AM to 2 PM) suggest a need for optimal staffing and resource allocation during these hours to ensure efficient operations and user satisfaction. Consider scheduling more staff or offering additional support services during these peak times.

- Space Utilization:

With weekdays experiencing significantly higher traffic than weekends, consider evaluating the effectiveness of the space and resources available during these peak days. This could also be an opportunity to promote the library as a study space during less busy times, like weekends, to even out usage.

- Targeted Programs and Services:

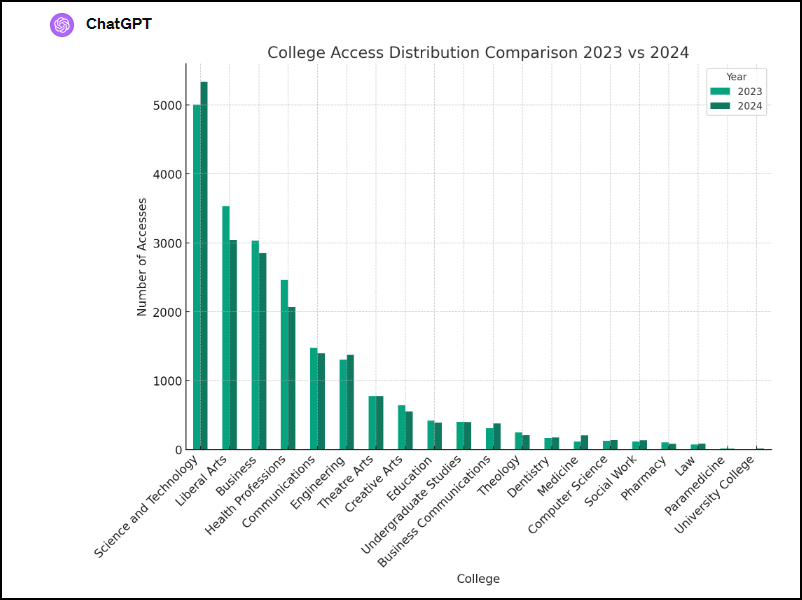

The data shows varying access patterns among different colleges. Tailoring programs or workshops to the needs and schedules of students from colleges with the highest foot traffic (e.g., Science and Technology, Liberal Arts) could improve engagement and utilization of library resources.

For colleges with increasing access year over year, such as Engineering and Medicine, consider collaborating with faculty to offer specialized resources or services that support these disciplines.

- Security and Access Control:

The analysis did not directly address security, but consistent monitoring of access patterns can help in identifying any irregularities or security concerns. Ensuring that access control systems are up to date and conducting regular reviews of access logs can enhance security measures.

- Observations:

The significant access by the Science and Technology college, particularly its increase from 2023 to 2024, suggests a high engagement level that might correlate with specific resource needs or study patterns. This could warrant a closer look to ensure resources meet demand.

The decrease in accesses for the Health Professions and Liberal Arts colleges might reflect changes in enrollment, curriculum delivery methods (e.g., more online resources), or shifts in study habits. It would be useful to investigate these trends further to adapt library services accordingly.

The notable increase in Medicine and slight increase in University College suggest growing areas of academic focus or expansion. These trends could guide future resource acquisitions or service expansions.

Human Reflections

The analysis provided by ChatAI is quite thorough, even insightful, given the limited quantity of data provided. Imagine what we might learn with more numbers, or the efficiencies we might gain by refining these queries. Of course we need to be concerned about replicating our analysis, and hallucinations can be problematic. In this case, ChatGPT (4) allows me to peek under the hood by viewing the Python codes used for analysis. I can also share the query and response with others through a QR code or link. But I like how ChatGPT presented its analysis in an organized and usable style that is easily shared with others, like colleagues in access services and facilities. What a wonderful way to initiate a conversation with human stakeholders.

I incorporated another hint from Jenny, one based on research. She suggests we use polite, respectful and encouraging language when conversing with ChatGPT. While this can actually provide better responses, it also created a relationship that felt like a partnership as we worked through the analysis together. The conversation became a collaboration, and that tight division between human and AI seemed less obvious to me.

Thank you to Hyangeun and to all the library staff who provide guidance (through workshops and consultations) on best practices as we explore and understand AI tools in our work.