![]() Check out new podcasts made by your classmates! This course (Fall 2021), may have been the best yet!

Check out new podcasts made by your classmates! This course (Fall 2021), may have been the best yet!

Learn about Paul Bunyan, the Kitchenaid Mixer, Hershey, Smokey the Bear and more!

![]() Check out new podcasts made by your classmates! This course (Fall 2021), may have been the best yet!

Check out new podcasts made by your classmates! This course (Fall 2021), may have been the best yet!

Learn about Paul Bunyan, the Kitchenaid Mixer, Hershey, Smokey the Bear and more!

During their time in the White House as the First Lady and President, Jackie and John F. Kennedy changed everything about how Americans see their First Family. Of course, their visibility as they arrived in Washington had owed a great deal to the fact that it coincided with the growth in popularity of television, but a huge factor in their popularity and their cultural relevance was how Jackie wanted herself and her family to be represented.

[1]

[1]

Jackie’s famous style has become iconic in its own right. The way she presented herself gave rise to the Kennedy’s image of royalty, or as close as they could get in the United States. The focus on fashion in the White House was something that Americans had never seen before and naturally led to high levels of fascination. Despite things lurking beneath the public’s point of view, such as John F. Kennedy’s poor health and myriad of extramarital affairs, Jackie Kennedy was great at exhibiting elegance and poise. Even in the face of tragedy, she exuded these traits.

The day of JFK’s assassination, she was adorned in her now famous pink jacket and pillbox hat. During Lyndon B Johnson’s swearing in session following the traumatic moment of his death, she kept her outfit on, still stained in her John’s blood. It is a wonder that she kept her cool enough to choose to show the world what had happened to her husband. Newly widowed and covered in her husband’s blood, she remained the Jackie Kennedy people had expected. During the planning of the funeral procession, she still showed her strength and her awareness that the image of her husband’s time as president was paramount. She fought to have a dramatic and marvelous funeral to honor JFK because she truly believed he deserved it.

[2]

[2]

Jackie Kennedy set the new standard for First Ladies both in the spotlight and behind the scenes by being extremely marketable and popular to the average citizen and by being strong willed and resolute with her family and peers. She created a feeling of majesty for the First Family and engineered the viewpoint of JFK’s term as president as the United States of America’s Camelot. Her achievements for the image of her family are something that future First Families will strive for, but in all likelihood will never attain.

[1] Harper’s Bazaar, https://www.harpersbazaar.com/fashion/trends/g1370/jackie-kennedy-onassis-style-0111/?slide=24

[2] http://yournewswire.com/jfk-jackie-bloodstained-suit/

When I learned about the Kennedy Assassination in high school, I read a report from a British journalist, who attended Kennedy’s funeral and claimed that “Jacqueline Kennedy has today given her country the one thing it has always lacked, and that is majesty.”[1] This statement left me with a deep first impression about this prominent first lady. Historian Michael Hogan points out that after President Kennedy was assassinated, not only did Jackie bury his body at Arlington National Cemetery, she also helped to establish the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C. and the Kennedy Library and Museum in Boston.[2] Jackie wanted the American public to remember President Kennedy as a war hero and a charming intellectual leader who demonstrated an appreciation of art. However, Jackie played a critical role to construct the public memory of President Kennedy even before he was assassinated.

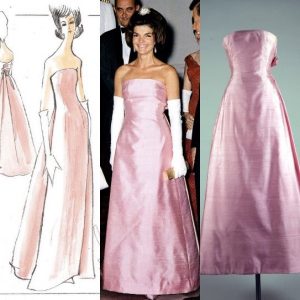

During Kennedy’s presidency, Jackie had become an American icon through her fashionable appearance. Jackie’s iconic fashion reflected Americans’ obsession with the appropriate demonstration of gender. Her elegant appearance demonstrated how her gender role became an important element that made a positive influence on her husband’s collective memory. Oleg Cassini was Jackie’s costume designer and he claimed that Jackie’s clothes “could reinforce the message of her husband’s administration.” [3] In addition, her role as a wife and a mother of two children helped the public to link President Kennedy with the image of a loving husband and father.[4] Along with the image of President Kennedy’s charming youth, Jackie’s iconic fashion style reinforced a positive public memory of President Kennedy. Jackie presented a new fashion look that combines American style with European elegance, which established an appealing American version of royalty and turned herself into a graceful American “queen”.[5] Because Jackie’s dignified fashionable appearance presented the vigorous image of the United States as a powerful modern nation, her elegant costumes emphasized the growth of American power and the prosperity during Kennedy’s presidency. Jackie played a significant role to help construct the image of President Kennedy and herself as a flawless couple and perfect family. This idealized version of American life appealed to the American public and strengthened people’s positive memory of President Kennedy.

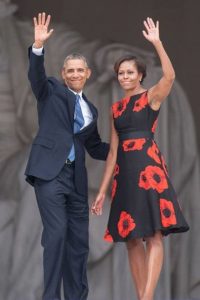

Similar to the way that Jacqueline Kennedy became an icon of fashion, social emphasis on the wardrobe choices of former first lady Michelle Obama also shows how female icon can be associated with the expectations of gender appearance in American society. Even though they came from different backgrounds, Michelle Obama is considered the second Jacqueline Kennedy due to the comparison of their fashion choices.[6] The dressing style of both first ladies have made different impacts on the American society in their times. For instance, Jackie’s strapless gown became the popular “Jackie Look” across the country in the 1960s.[7] The “modified A-line gown of pink-and-white silk” that she wore in a White House dinner became the most eye-catching news of the event.[8] Likewise, Michelle Obama wore a “custom-made pink and gold silk dress” during her speech at the Democratic National Convention in 2012 and it became the best-selling dress of the designer.[9] Another dress, the “black dress with big red poppies” that she wore during the 50th anniversary of the 1963 march on Washington D.C., is displayed at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture.[10] These examples show how the American public obsession with the dressing choices of first ladies can turn them into fashion icons. The connections between notable female icons and the way they present themselves reflect the social expectations placed on the appropriate appearance of females.

Jacqueline Kennedy and Michelle Obama are both beloved first ladies throughout American history. Moreover, they are popular female icons that represent the American fashion style. Jacqueline Kennedy demonstrates how gender role became an element in shaping the public memory of President Kennedy. Jacqueline Kennedy and Michelle Obama rose to the status of fashion icon based on similar characteristics. The historic representations of both first ladies demonstrate a potential social expectation of gender appearance in American society.

[1] Peggy Noonan, The Time of Our Lives: Collected Writings (New York: Grand Central

Publishing, 2015), 210.

[2] Michael J. Hogan, The Afterlife of John Fitzgerald Kennedy: A Biography (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2017), 5.

[3] Ibid., 33.

[4] Ibid., 41.

[6] Scott Whitlock, “ABC Hosts Swoon Over ‘American Icon’ Michelle Obama, Compare Her to

Jackie Kennedy,” Media Research Center. November 10, 2010, http://archive2.mrc.org/bias-alerts/abc-hosts-swoon-over-american-icon-michelle-obama-compare-her-jackie-kennedy (accessed April 4, 2018).

[7] Hogan, The Afterlife of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, 33.

[8] Ibid., 34.

[9] Vanessa Friedman, “What Michelle Obama Wore and Why It Mattered,” New York Times,

January 14, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/14/fashion/michelle-obama-first-lady-fashion.html (accessed April 4, 2018).

[10] Ibid.

According to Mirror Mirror: Eating Disorder Help, if Barbie was a real woman, she would be 5’9” and weigh 120 pounds[1]. Her body fat percentage would be so low that she would not be able to menstruate.[2] So, if we allow children to play with such dolls, are we supplying them with unnecessary ideals of the female body?

Many Barbie dolls take on the average character of the happy cheerleader or shopping Barbie as seen above. In M.G. Lorde’s Forever Barbie, “For every fluffy blond cheerleader who leaps breast forwards into an exaggerated gender rule, there is a recovering bulimic who refers to wear dresses and blames Barbie for her ordeal.” [3]In a way, Barbie has set up these gender roles and standards for women of all ages. Women feel the need to be skinny based on the standards that society and the media lays out for them. I also feel that, Barbie has enforced this idea that pink is only a girls color, as seen in her many outfits and in your local Barbie toy aisle. So, it is extremely frowned for any boy to like the color pink, because it would automatically make him ‘girly.’

In one study, girls who played with Barbie reported lower body image and a greater desire to be thinner than girls who played with other toys. It all come down to the question if Barbie is teaching children that to be liked, you have to be thin, white and blonde.[4] Personally, I never felt the need to look this way, but I did feel inferior to people who were white and have blonde hair. The reason for this was because I didn’t look like the popular toy that other girls played with, so I had no representation out there that showed the color of my skin had beauty in it too. I am glad now that Mattel is introducing dolls that have different body types and skin tones, but is this representation of diversity better late than never?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMP2T5dwOtg

There are perhaps hundreds and thousands of girls and even women that dream of looking like Barbie. Of those those thousands, there are probably hundreds of females that have tried. In the video above, this is just one of the many cases where women have undergone many surgeries in order to look like the famous doll. She event states that people have called her plastic and fake, but she doesn’t care what they think as they are all just “jealous.” She has also set up a savings account of $20,000 for her daughter in case she wants plastic surgery as well. I am not for or against plastic surgery, as I feel that if you are not satisfied with the way you look, you have every right to change it. However, when it comes to looking like a plastic doll, I am not sure where the line

[1] “Barbie and Body Image,” Mirror Mirror Eating Disorder Help, last modified 2016, accessed March 29, 2018 https://www.mirror-mirror.org/barbie-and-body-image.htm

[2] Ibid.

[3] Lord, M. G. Forever Barbie: The Unauthorized Biography of a Real Doll. Fredericton, N.B.: Goose Lane Editions, 2004. 14.

[4] “Barbie and Body Image,” Mirror Mirror Eating Disorder Help, last modified 2016, accessed March 29, 2018 https://www.mirror-mirror.org/barbie-and-body-image.htm

When I first found out that we were going to discuss American Gothic in class, I had no idea that we were going to talk about this painting. I didn’t think that the name of the painting would be American Gothic, because the only thing that seemed to make it “gothic” was the window. I was curious about what my friends would think about the painting because I knew that their analysis would be different from those in the class. I say this because I feel that as a class, we are more concerned with deeper meaning associated with the painting, such as the meaning of every little detail in the painting like the design of the house. However, I knew that my friends would be more honest and genuine about what their first thoughts on the painting. My first friend said that the painting made him think of, “angry white racist people.” He said he thought this because it looked the painting was based on a southern couple on a farm.

It is a common stereotype that people living in the south are “racist rednecks,” or that some families may even marry within their family. This can be seen when my friend took this stereotype even farther, and asked me if the couple in the painting were either. “related, married, or both,” and that they look like Trump supporters. I found it very interesting that such a plain looking painting could spark so much thought and connections to these stereotypical values of Americans in the South.

Another friend told me that the painting made her feel bored as it is very neutral and looks like just a simple life. A different friend told me she had no opinion of it at all because it is just such a boring painting. I found it very interesting that one friend though this painting screamed racism and anger, while the two other friends thought of it as nothing at all. Their views may show that they think the average southern American couple is a redneck, or a boring farmer. Everyone interprets art in different ways, but if an interpretation is so far off from the original artist’s intention, does that make the interpretation wrong? Grant Wood did not intend for people to believe that he used this painting to “satirize the narrow-mindedness and repression that has been said to characterize Midwestern culture.”[1] He denied any accusations of this. Yet, people still make the connection that this painting of a small town life of a boring couple on their farm. I think that because this painting can have so many different interpretations and is so ambiguous it makes it an icon. The painting can portray a couple that is “rich or poor, urban or rural, young or old, radical or redneck,”[2] but in the end, what the painting truly portrays, is that it is American.

[1]The Art institute of Chicago. “American Gothic.” Art Access: Modern and Contemporary Art. Accessed March 15, 2018. http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/exhibitions/Modern/American-Gothic.

[2] Wanda Corn, The Birth of a National Icon: Grant Wood’s American Gothic (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1983) 272.

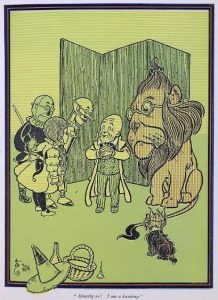

When L. Frank Baum created The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900, he probably did not envision it becoming one of the most legendary pieces of literature in American history. The chances that he saw the direction it would take itself are even slimmer. The children’s story that also (likely) served as an allegory for 19th century populism is, at this point, more well known for its 1939 film adaptation, this time titled The Wizard of Oz. The movie adaptation focused itself on the fantastical world created by Baum and featured songs written specifically for the movie that have become iconic in their own right. For example, it is hard to think of the story separately from “We’re Off to See the Wizard,” and “Over the Rainbow” was named the best song of the 20th century by the Recording Industry Association of America.[1] The film turned the story into one of the most well known ever, which is certainly an accomplishment, but in doing so, the story of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz lost its original allegorical significance. Instead, The Wizard of Oz is thought of as one of the greatest family movies and Oz came to be a wondrous and fantastical paradigm of utopias in cinema. ![]() [2]

[2]

Following the 1939 film adaptation, the story was adapted into another musical and subsequent film, The Wiz, this time featuring an all-black cast, all new songs, and a re-imagination of the land of Oz in a New York City setting.

In his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin argues that “the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition.”[3] In the case of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, this could certainly be true. In the adaptations of Baum’s original story, the original allegory was lost as the overall themes changed to match the times of their respective releases. The way the recreations altered the way people think of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is naturally due to the changes made in each story, but that does not mean the original is tainted or disrespected: the tale likely owes its iconicity to these recreations. Martin Kemp, who disagreed with Benjamin over the effects of reproduction, said: “any widespread broadcasting of fame ensures that the embodying of a special presence in the original is enormously enhanced.” [4] In the case of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, both are certainly true. Much of the original story changed, but the wonderment and the whimsy remained.

[5]

[1] “Best Songs Of The Century?” CBS News, March 08, 2001, accessed March 01, 2018, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/best-songs-of-the-century/.

[2] The Wizard of Oz (1939).

[3] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”

[4] Martin Kemp, Christ to Coke: How Image Becomes Icon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[5] The Wiz (1978).

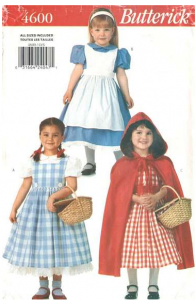

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz written by author L. Frank Baum in 1900 is one of most classic Children’s novel in the United States. Dorothy, a young farm girl from Kansas with her dog Toto, begin the adventures in the magical Land of Oz after they are swept away from home by a cyclone. Similar to other beloved female characters such as Alice who wore puffed sleeve dress with white pleated sweetheart neckline and Little Red Riding Hood who wore the red cape have become classic fashion, Dorothy’s blue and white gingham check dress is also a notable icon. Not to mention that her magic silver slippers (ruby red in the movie in 1939) is as powerful as the magic wand of Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother! The story of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is an American icon which illustrates the characters’ convinced beliefs of the American dream, represents the populist movement in the late 1800s, and implicates political messages of the current American political landscape.

In the story, Dorothy was told by Witch of the North that she needs to go to the Emerald City in the Land of Oz to seek for help from the Wizard of Oz, who might be able to help her get back home.[1] On her way to the Emerald City, Dorothy became friends with a Scarecrow, a Tin Man and a Cowardly Lion who joined her journey. All of them are pursuing something that would make themselves a better being or for something that they want. Dorothy wants to go home, the Scarecrow is looking for a brain, the Tin Man wants a heart, the Lion wants to obtain courage. Throughout the journey, the Scarecrow he consistently comes up with smart ideas whenever the team faces a challenge, the Tin Man processes emotions through his caring for his friends. He even cries over the death of a beetle, and the Cowardly Lion demonstrates courage when he carries his friends and jumps over deep ditch. During the journey, they fail to realize that they already possess the things they unconsciously want. Rather, they all believe that they are missing something only the great Oz can provide and that they can only achieve their goals in the Emerald City.[2] Even though Oz told them that he cannot grant them their wishes, the Scarecrow, the Tin man and the Lion refused to listen.[3]

The way that they finally arrived at their dream place, the Emerald City in the Land of Oz, after they overcome many challenges is similar to the promise of American dream. If one works hard, anyone can reach the dream of the middle class. They felt satisfied only when Oz provides them with symbolic objects that represent a brain, a heart and courage. Their satisfaction exposes the impact of American dream in their beliefs. They believe that achieving their goals from Oz is the only way to approve their hard work to arrive at Emerald City has pay off. This demonstrates the powerful impact of the American dream, which contribute the novel as an iconic American story.

Another aspect that makes The Wonderful Wizard of Oz an American icon is the Populist elements that implies in the story. In 1964, historian Henry Littlefield points out the novel is an allegory of the Populist movement in the 1890s.[4] The rise of Populist Party was organized by common people such as farmers and factory workers who united to form a third-party to challenge power from bankers and business leaders.[5] Littlefield argues that the Scarecrow in the story represents “self-doubt” American farmers who demonstrate “a terrible sense of inferiority” during this period. [6] The Tin Man symbolizes factory workers who have been dehumanized by the big business. [7] Because there were many Populists advocated the federal government to adopt the monetary policy for free minting silver money during the economic depression in 1893, Littlefield interprets the Oz’s yellow brick road as the existing gold standard and indicates Dorothy’s silver shoes represents the free silver movement.[8]The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is a Populist allegory, which contains elements that reflects the social and political movement in the late 1800s.

The iconic association between the novel and politics is remained today as it has been used to convey messages in current American political climate. Even though everyone believes that Oz is a powerful leader, Dorothy and her friends uncover that the great Wizard of Oz is simply an ordinary man towards the end of the story. He used a variety of tricks that allowed him to be regarded as a powerful Wizard. CNN Journalist Jeanne Moos disapproves the way that the President Donald Trump intended to avoid answering any questions about the Republican tax deduction plan by taping himself talking on two TV screens rather than physically being present during White House press briefing to is similar to Wizard of Oz, who tries to maintain his authority by cunning and avoid presenting his actual appearances in front of the public. [9]In the article “Trump is like ‘Wizard of Oz,’” author Ed Sokalski satirically criticizes the administration of Trump by indicating that his inefficient leadership just as the incapability of Wizard of Oz, an ordinary man with no special power.[10] The story demonstrates the notion of questioning the untruthful leadership has continually being used by political critics today.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is an American icon in multiple aspects. The story demonstrates the American belief that hard work pays off. It also highlights the elements of Populist movement, and exposes unreliable leadership, which has remain being used to challenge current political leader.

[1] L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (New York: George M. Hill Company, 1900).

[2] Ibid., 55.

[3] Ibid., 131.

[4] Peter Liebhold, “Populism and the World of Oz,” National Museum of American History.

Smithsonian, November 2, 2016, http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/populism-oz (accessed February 28, 2018).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[9] “CNN playfully mocks Trump’s ‘Wizard of Oz’ act at the White House press briefing,” The Week, January 5, 2018, http://theweek.com/speedreads/746838/cnn-playfully-mocks-trumps-wizard-oz-act-white-house-press-briefing (accessed February 28, 2018).

[10] Ed Sokalski, “Trump is like ‘Wizard of Oz,’” The Morning Call, February 23, 2018, http://www.mcall.com/opinion/letters/mc-sokalski-trump-wizard-oz-curtain-20180223-story.html (accessed February 28, 2018).

When thinking about national statues and monuments, my mind flashed back to a picture I saw when I was twelve and nearing the height of my Jonas Brothers obsession. It was a photo of the three brothers at the Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. I knew nothing about the statue at the time but I was struck by how massive and looming it was compared to the size of an average human. I was even more captivated when I came across photos that showed the statue looking out over the city’s vast landscape of skyscrapers, mountains, neighboring islands, and water. Christ the Redeemer may seem to have little in common with the U.S.’s Statue of Liberty (for starters, it’s a him/Him…) but the two iconic structures have one striking similarity: they are what their people want them to be.

When thinking about national statues and monuments, my mind flashed back to a picture I saw when I was twelve and nearing the height of my Jonas Brothers obsession. It was a photo of the three brothers at the Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. I knew nothing about the statue at the time but I was struck by how massive and looming it was compared to the size of an average human. I was even more captivated when I came across photos that showed the statue looking out over the city’s vast landscape of skyscrapers, mountains, neighboring islands, and water. Christ the Redeemer may seem to have little in common with the U.S.’s Statue of Liberty (for starters, it’s a him/Him…) but the two iconic structures have one striking similarity: they are what their people want them to be.

The idea for Cristo Redentor, as it is known in Portuguese, came from the people of Brazil themselves. Although the country had gone through a separation of church and state at the end of the 19th century, a group of Brazilians who feared “an advancing tide of Godlessness” throughout the country and the world after World War I decided that there was a need for a national symbol that would reclaim Brazil — and Rio, its capital city at the time — as a land of Christianity. [1] The group, the Catholic Circle of Rio, organized an event to collect donations and signatures to support the building of the statue and considered many designs before choosing engineer Heitor da Silva Costa’s image of Christ with arms outstretched as a symbol of peace. French sculptor Paul Landowski led the creation of the 98-foot tall statue, which is made out of soapstone and concrete, and after nine years of construction, Christ the Redeemer officially opened on Mount Corcovado in 1931. [2]

Now, a statue with a founding based entirely on one specific religion may seem to run counter to the secular American values of freedom and democracy that the famous Statue of Liberty has come to represent, but I feel that both are examples of how the values that are associated with icons can change over time while still retaining a sense of national pride. Historian Bernard Dard writes that while Lady Liberty has been used by everyone from business firms to cartoonists for a variety of purposes — from commercial product promotion to advocacy of liberal immigration laws and criticism of the government — her core symbolism as the bearer of American ideals such as liberty, opportunity, and democracy (and as America itself) has remained intact and transcended all else. [3]

In a similar way, although Christ the Reedemer began as a symbol of Christianity, it is not exclusively so and it has also acquired a greater significance. According to a BBC article, Count Celso, one of the first to be involved with project in its early stages during the 1920s, described the finished statue as “a monument to science, art and religion.” [4] The rector of the chapel that sits inside the base of the statue (the pedestal that elevates its full height to 125 feet) calls it a religious, cultural, and national symbol for Brazil and a means of welcoming all those who pass through Rio, almost like a host. And for a local sorbet vendor, who is also quoted in the article, the statue is a beautiful place with special significance to the community around it. [5] Christ the Reedemer stands as a representation of the Brazilian people’s accepting and warmhearted attitude towards all visitors to Rio and citizens of the world, just like the welcoming and protective qualities that have been attributed to the Statue of Liberty over time as she has greeted new arrivals to America — “From her beacon-hand/Glows world-wide welcome,” as Emma Lazarus’s famous poem states. [6]

In a similar way, although Christ the Reedemer began as a symbol of Christianity, it is not exclusively so and it has also acquired a greater significance. According to a BBC article, Count Celso, one of the first to be involved with project in its early stages during the 1920s, described the finished statue as “a monument to science, art and religion.” [4] The rector of the chapel that sits inside the base of the statue (the pedestal that elevates its full height to 125 feet) calls it a religious, cultural, and national symbol for Brazil and a means of welcoming all those who pass through Rio, almost like a host. And for a local sorbet vendor, who is also quoted in the article, the statue is a beautiful place with special significance to the community around it. [5] Christ the Reedemer stands as a representation of the Brazilian people’s accepting and warmhearted attitude towards all visitors to Rio and citizens of the world, just like the welcoming and protective qualities that have been attributed to the Statue of Liberty over time as she has greeted new arrivals to America — “From her beacon-hand/Glows world-wide welcome,” as Emma Lazarus’s famous poem states. [6]

Native songwriter Gilberto Gil perfectly captured this essence surrounding Christ the Redeemer and Rio’s culture in his 1968 song “Aquele Abraco” (translated as “That Hug”):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oCB6wQ1R0WA

——————————

1. Boorstein, Michelle. “The many meanings of Rio’s massive Christ statue.” The Washington Post. August 09, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/acts-of-faith/wp/2016/08/09/the-many-meanings-of-rios-massive-christ-statue/?utm_term=.a28d827cdec9&wpisrc=nl_faith&wpmm=1.

2. “Christ the Redeemer (statue).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christ_the_Redeemer_(statue)#cite_note-The_Sun-10.

3. Dard, Bertrand. “Liberty as Image and Icon.” In The Statue of Liberty Revisited. Smithsonian Institution Press.

4. Bowater, Donna, Stephen Mulvey, and Tanvi Misra. “Arms wide open.” BBC News. March 10, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/special/2014/newsspec_7141/index.html.

5. Ibid.

6. Lazarus, Emma. “The New Colossus by Emma Lazarus.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46550/the-new-colossus.

7. “Aquele Abraço – Gilberto Gil.” Www.letras.mus.br. https://www.letras.mus.br/gilberto-gil/16138/.

![]() The Godfather films are an epic saga that is often credited as some of the best films ever made. Within its narrative is a cultural tie between the criminal underworld and the American Dream. Francis Ford Coppola, the director, has remarked “it’s not a film about organized gangsters, but a family chronicle. A metaphor for capitalism in America”[1]. Besides these ideas of capitalism there are other concepts with gender roles as well. The use of an icon like the Statute of Liberty in these films represent these two concepts. As cited in the third chapter, Bodnar cites how from the beginning, Americans associated through the Statute of Liberty, concepts like liberty with capitalism. “It is not the pursuit of happiness that allies with life and liberty as inalienable rights, but property that anchors and stabilizes American liberty.”[2]

The Godfather films are an epic saga that is often credited as some of the best films ever made. Within its narrative is a cultural tie between the criminal underworld and the American Dream. Francis Ford Coppola, the director, has remarked “it’s not a film about organized gangsters, but a family chronicle. A metaphor for capitalism in America”[1]. Besides these ideas of capitalism there are other concepts with gender roles as well. The use of an icon like the Statute of Liberty in these films represent these two concepts. As cited in the third chapter, Bodnar cites how from the beginning, Americans associated through the Statute of Liberty, concepts like liberty with capitalism. “It is not the pursuit of happiness that allies with life and liberty as inalienable rights, but property that anchors and stabilizes American liberty.”[2]![]()

The Godfather was one of the first films of New Hollywood cinema, and the first film since the early 1930s to feature criminals in main role instead of a secondary character[3]. In Italian-Americans in film, the author states the film, “…became the prototype and most important legitimator of the new wave of Italian-American sex-and-violence odysseys”[4] The film became a huge success and a cultural touchstone because of its complicated narrative and overall quality of production.

On the surface, the film presents typical gender roles “The older generation the traditional earth mothers, provide passive and stoic support for their men. The younger…. Modern nags become Italian-American spoiled brats”[5] Though there is evidence in the film of subversion of gender roles, visually and narratively traditional gender roles are reinforced. The Statute of Liberty in these scenes can be seen as a heightened extension of “earth mother” of the older generation as cited by Cortes. This connection has been linked to the statute itself in the past, “Standing upon the threshold of New York, which is the doorway of the Union, she will seem to offer the freedom of the New World to the thousands that shall flock to us from the Old…”[6] This line shows how people imprinted maternal qualities onto to the Statute because of her gender, and her connection to immigration.

![]() In one scene in The Godfather some underlings of Don Vito assassinate a guy on the outskirts of New York, in the background the Statute of Liberty is in view in a sense “watching” everything happen. The scene alone juxtaposes the ideas of the American Dream the Statue with its representation of freedom, with these gangsters, who commit crimes in pursuit of the American Dream. Visually this scene resembles one of the last scenes in the film where Kay looks through the doorway (at the moment) unaware of her husband’s position as the head of a criminal organization. Both scenes place women (in one case the Statute of Liberty) as passive observers to corruptions of the American Dream.

In one scene in The Godfather some underlings of Don Vito assassinate a guy on the outskirts of New York, in the background the Statute of Liberty is in view in a sense “watching” everything happen. The scene alone juxtaposes the ideas of the American Dream the Statue with its representation of freedom, with these gangsters, who commit crimes in pursuit of the American Dream. Visually this scene resembles one of the last scenes in the film where Kay looks through the doorway (at the moment) unaware of her husband’s position as the head of a criminal organization. Both scenes place women (in one case the Statute of Liberty) as passive observers to corruptions of the American Dream.

This final connects the narrative of The Godfather with the immigrant experience, and executes this by invoking the Statue of Liberty. Once again, the Statute is cast as an observer, this time a witness to the origins of the Godfather himself. The fictional character presents an immigrant narrative that is rooted in American history. “The individualistic liberties with which arriving immigrants invested the Statue of Liberty—as linked to preconceptions or early impressions of America—often emphasized hopes for new prosperity and wealth.”[7] This new prosperity is exactly what the Godfather achieved, the complication is that this was achieved through notorious means. It is this paradox that has made the narrative so engaging almost forty years after the films were released. The power of this legacy is consistently tied with the iconography and the mission of the American Dream, and this is best exemplified in the films’ use of the Statute of Liberty.

![]()

![]()

Fig 1-2 Scenes from The Godfather[8]

![]()

Figure 3 Scene from The Godfather Part II[9]

[1] Browne, Nick Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Trilogy Cambridge University Press, 2000 28

[2] Bodnar John The Changing Faces of the Statue of Liberty 2005 62

[3] Browne, Nick Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Trilogy Cambridge University Press, 2000 81

[4] Cortes, Carlos Italian Americans in Film: From Immigrants to Icons Oxford University Press 1987, 117

[5] Ibid., 117

[6] Bodnar, John The Changing Faces of the Statue of Liberty 2005 98

[7] Ibid., 102

[8] Coppola, Francis Ford The Godfather 1972 Paramount Pictures (images found on Netflix)

[9] Coppola, Francis Ford The Godfather Part II 1974 Paramount Pictures (images found on Netflix)

![]() The moment I thought to write about the Statue of Liberty as a strong female icon, I immediately found some depiction of her deep in the abyss of my television knowledge. The animated Netflix show, Big Mouth, follows the exploits of young teens trying to navigate the art of becoming an adult. In the second episode of the series, the kids take a field trip to the Statue of Liberty, where Jessi gets her first period. The Statue of Liberty takes Jessi into her hands and gives her the harsh facts about being a women in today’s society.

The moment I thought to write about the Statue of Liberty as a strong female icon, I immediately found some depiction of her deep in the abyss of my television knowledge. The animated Netflix show, Big Mouth, follows the exploits of young teens trying to navigate the art of becoming an adult. In the second episode of the series, the kids take a field trip to the Statue of Liberty, where Jessi gets her first period. The Statue of Liberty takes Jessi into her hands and gives her the harsh facts about being a women in today’s society.

Portrayed as a French-speaking, cigarette smoking, doesn’t-take-crap-from-anyone kind of woman, the Statue of Liberty asserts herself as the strong, independent figure we believe she is. However, she is a hopeless pessimist who does not find any inspiration in herself. Even when Jessi accuses the Statue of being a bit cynical, the Statue sarcastically apologizes for not being “more America, sunny Mickey Mouse”. Here, not only does the Statue of Liberty represent women, but she depicts the age old struggle of women by saying that life is hard and there aren’t very many good things about being a woman in a male driven society. Liberty has stood in the New York Harbor for decades and has yet to see a woman rise to power in America.

, , , and . 2005. The Changing Face of the Statue of Liberty. Bloomington: Center for the Study of History and Memory, Indiana University.