By Tauheedah Shukriyyah Asad

When I first conceptualized “Diggin’ Philly: The Black Philadelphia Project,” my approach to capturing and preserving elements of the city’s history was based on my training in journalism and MSP (media studies and production. I knew the City of Brotherly Love had a rich tradition of Black excellence. I’d heard the stories from family members, elders, and comrades. I’d searched the internet; frequently visited historic sites, and attended cultural events and exhibits where stories of Black Philadelphia were being told in parts. As a master’s student, I became fascinated with digital storytelling. And as I learned more about Philadelphia— the land of my father, I tried to figure out the best ways to keep these stories alive and accessible. How could I develop an effective framework to document, celebrate and preserve the cultural heritage of this city and other Black spaces for future generations.

This journey, which has been an iterative process (as most qualitative research tends to be), led me to the field of digital cultural heritage. I was both excited and relieved to learn that a growing number of scholars shared this interest, and were doing the work in different ways across many disciplines.

Vacker (2019) wrote, “Media technologies, industries, content, and usage have converged to shape consciousness and culture as technological environments centered on screens.” For this reason, researchers are constantly thinking about ways to incorporate digital tools and practices into our work as we rapidly move toward a digitally-centric society.

This fall, I facilitated a workshop on digital practices for the study of urban heritage for the Digital Scholar’s Studio. I was surprised to receive such positive feedback, and requests to further explore this topic with the Temple community. The fact is, many people are doing this work and don’t even know it!

In this blog series, I’ll provide an overview of digital cultural heritage research in three parts: (1) define cultural heritage research and its significance, (2) discuss popular working methods in digital cultural heritage work, and (3) address ethical considerations and collaborative construction of digital heritage.

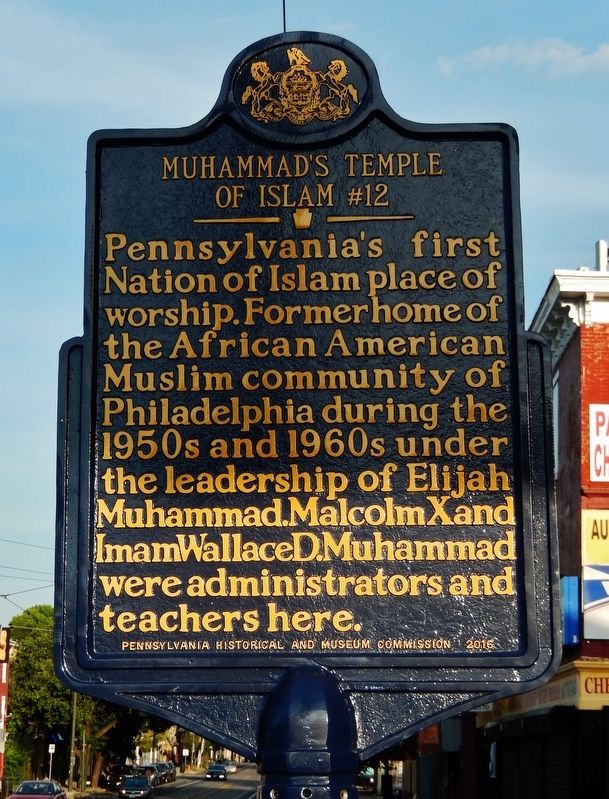

Muhammad’s Temple of Islam #12 Historic Marker featured in the Black Philly Muslims Collection of my “Diggin’ Philly” Project

Defining Digital Cultural Heritage Research

Cultural heritage research focuses on sites, objects, and intangible things (e.g. customs, beliefs, or rituals) of cultural, ethnological, or historical value to groups and individuals. The rise of the internet, social media platforms, electronic devices, and software offer the potential to enhance the way we engage with existing cultural assets. The use of these emerging technologies in the service of understanding and preserving cultural assets is referred to as digital heritage (Sullivan, 2016; UNESCO.org).

Traditional cultural heritage materials include artifacts— buildings, architectural structures, statues, and art; and archival materials— maps, photos, videos, texts, and audio recordings. These materials are typically curated and stored in galleries, libraries, archives, and museum (GLAM) repositories sometimes referred to as “memory institutions.” But who decides what materials are worthy of preservation? What criteria exist for these institutions, and what are their limitations? Who has access to these materials?

Through digital practices, GLAM institutions are able to extend the services they provide to a wider audience. But digital heritage work is more than the act of digitizing physical artifacts (though this is important!). By centering media and communication technologies in our work, we can provide a different kind of cultural experience using real-time, immersive, and interactive techniques.

The Significance of Digital Heritage Projects

The digital age is often lauded as being the great democratizer of information and access. We know this isn’t entirely true (and we’ll discuss this in part 3 of this blog series). Still, in many ways, it serves as a tool of empowerment for vulnerable people to shift the balance of authority in academic work and cultural practices.

Digital heritage projects often address concerns about the representativeness in collections throughout the history of memory institutions. The push for racial equity and inclusivity in the GLAM industries and academia has been going on for as long as I can remember. Several studies like Museums so White show an extreme lack of diversity in academic and media institutions. This is often reflected in the level of support or institutional backing received for projects produced by, and centering, people from marginalized communities.

The counternarratives generated through digital heritage research are not only a means to resist hegemonic norms in the humanities but a way to challenge what society considered to be “inherently valuable” about the past. Through digital cultural research, we are able to reveal the subaltern— that which is “unseen, unknown, undervalued, and untold” (McCandlish, 2017).

This was the motivation behind A Philly Jawn: Curated Black Geographies. Dr. Synatra Smith and I teamed up to co-create this project which explores the way digital humanities can be used as a tool to disrupt traditional manifestations of place, space, and materiality to center anti-racist research in its place. Our work was recently presented among other stellar projects of its kind at the Smithsonian’s Claiming Space Symposium last month.

Beyond the Basics: Recommended Reads

Here are three texts that I found insightful in assessing the value of digital scholarship in heritage research. I invite you to engage with these readings and see what resources are available and appropriate for your academic endeavors.

- Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse (Cameron & Kenderdine, 2007)

- Digital Cultural Heritage meets Digital Humanities (Leonardo, 2019)

- Digital Cultural Heritage (Kremers, 2020)