By Kaelin Jewell

Recently, I attended a lecture by Renata Holod, a specialist in the art and architecture of the Islamic world at the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of the History of Art. In her talk, which was sponsored by Temple’s Department of Art History, Prof. Holod discussed the reconstruction of an historical monument, the Great Mosque of Córdoba, and its medieval lighting system. While Prof. Holod described the project’s technical aspects, including the team’s use of the software program Maya, it was her candid discussion of various methodological concerns as they relate to digital reconstruction that were most illuminating. As I have mentioned in previous posts, I am a firm believer that digitally reconstructed historical monuments are inherently constructed. Everything visible in digital models is based on a series of carefully researched decisions from the floor plan used to the polychrome chosen to color the architectural members. In the digital model of the 10th-century CE Great Mosque of Córdoba, Prof. Holod and her team made the decision to reconstruct the lighting system based on surviving medieval Islamic lamps and illuminated manuscripts that depicted such systems inside architectural spaces. The end result is a carefully researched, yet still hypothetical representation of how the interior of the Great Mosque might have appeared to the medieval viewer:

During her talk, Prof. Holod stressed the importance of the decision making process and how the team had to make adjustments to the above reconstruction to account for issues such as surface reflections (the original floors would not have been so reflective, for example).

Ultimately, I think it’s important to remember that these problems are not limited to these 21st-century reconstructions. As we can see from both the 18th-century wooden model of Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre (left) and the 1980s hand-drawn reconstruction of the 6th-century CE Church of St. Polyeuktos in Constantinople (right), humans can visualize architectural space in a variety of ways. Both of these reconstructions are hypothetical and neither recreate the reality of the actual monument (the real Holy Sepulchre is not covered in mother-of-pearl and St. Polyeuktos most likely did not have a dome). All of these factors are important to remember as the hyper-realistic qualities of digital reconstruction continues to be applied to historic monuments. What is it that we are trying to achieve with these high-tech models and how does this impact notions of historical “accuracy”? These are questions I often ponder when working in Sketchup on buildings that are no longer standing–I don’t want to generate a false history of the past.

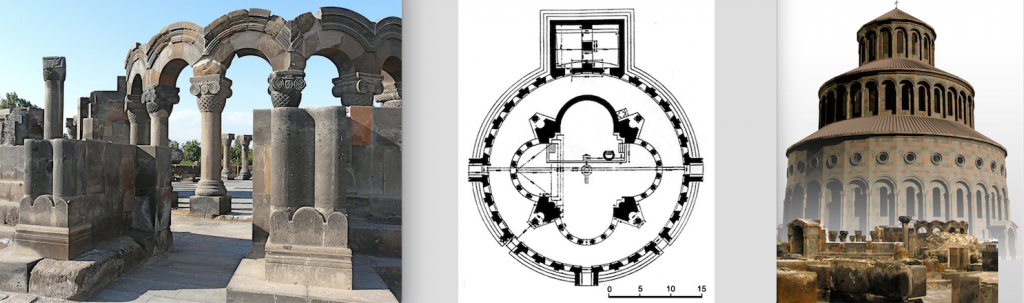

In a recent article, art and architectural historian Christina Maranci addressed these very issues as they relate to the early 20th-century reconstruction of the 7th-century CE church at Zvart’noc’ in Armenia, which has seduced scholars for decades. Towards the end of her essay, she reminds us that “Toramanyan’s beautiful representations of Zuart’noc’ present a symmetrical and regular monument of repeating cylinders and cones. It is a form easily committed to memory and often likened to a wedding cake, but not one that finds obvious parallels in surviving medieval architecture” (Maranci, 113).

References:

Bardill, Jonathan. “A New Temple for Byzantium: Anicia Juliana, King Solomon, and the Gilded Ceiling of the Church of St. Polyeuktos in Constantinople.” In Social and Political Life in Late Antiquity, eds. William Bowden, Adam Gutteridge, and Carlos Machado (Leiden: Brill, 2006): 339-370.

Nice job. Very interesting!