By SaraGrace Stefan

Introduction

How do we convey that which is beyond words? According to literary critic Teresa Goddu, gothic literature has historically served as the genre that allows authors to do just that: to “speak the unspeakable” (Goddu, 10). As a PhD student studying the gothic in the English department at Temple, I wanted my culminating project for the Cultural Analytics Certificate to investigate what hundreds of gothic novels would say if given the ability to speak, shriek, or moan in concert together. I specifically was curious to see what thematic focuses or recurring topics would emerge if I analyzed a large corpus of gothic texts from different time periods.

Although my dissertation does not directly employ digital methods, I find great value (and challenge!) in complementing my traditional scholarship with computational exploration. For my project, I decided to create a corpus of gothic literature and examine its thematic interests over time through topic modeling with Python. Needing to operate within copyright limitations, I decided to create my corpus exclusively from public domain texts available from Project Gutenberg, a library of free eBooks.

Building a Gothic Corpus: What Even is the Gothic?

Before I created my gothic corpus, I had to first define what I meant by “gothic literature,” – a notoriously difficult task! As Jerrold E. Hogle explains in the Introduction to The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction, the gothic is a “highly unstable genre” (Hogle, 1), that engenders much debate amongst his scholars, but there are certain identifiable characteristics that go beyond the mere presence of ghosts or castles.

Scholar Chris Baldick describes the gothic as the combination of “a fearful sense of inheritance in time with a claustrophobic sense of enclosure in space, these two dimensions reinforcing one another to produce an impression of sickening descent into disintegration” (Baldick, xix). More concretely, gothic texts, be they British, Irish, American, etc., invoke the specter of the past and interrogate its hauntological effects on the present.

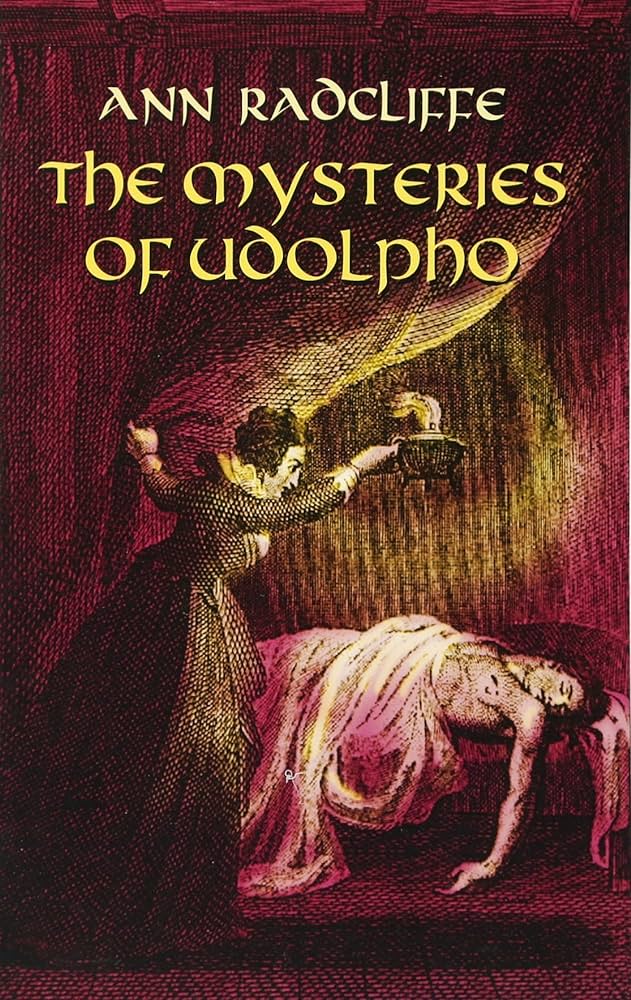

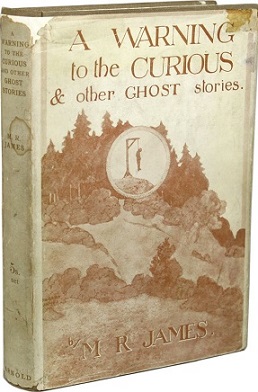

For my corpus, I selected 238 texts from Project Gutenberg, with the first 47 texts spanning from 1682 to 1816; the second quarter (45 texts) spanning from 1817 to 1890; the third quarter (45 texts) from 1891 to 1903; and the final quarter (46 texts) 1904 to 1925. These divisions were in an effort to make my data set smaller and easier to work with, but more historically-conscientious corpus divisions may be part of my future research.

My corpus for the time being contains available gothic classics such as Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), as well as lesser known texts like Elia Wilkinson Peattie’s The Shape of Fear (1898) and M.R. James’s A Warning to the Curious, and Other Ghost Stories (1925). Once I had created my corpus, I was ready to begin transforming the texts into machine-readable data for my topic model.

Topic Modeling the Gothic

There are a variety of online resources that will assist beginners with text analysis and topic modeling. For an introduction to text analysis in general, please look at my earlier blog post on the Cli-Fi and Banned Book projects, but for now, we will move straight to topic modeling.

As described by Andrew Goldstone and Ted Underwood in their article, “The Quiet Transformations of Literary Studies: What Thirteen Thousand Scholars Could Tell Us,” topic modeling is a method that attempts “to identify the thematic or rhetorical patterns that inform a collection of documents…These patterns we refer to as topics” (Goldstone, 361). More concretely, topic modeling is a kind of statistical modeling that uses unsupervised machine learning to identify recurring clusters of words within a corpus of texts.

For their study, Goldstone and Underwood extrapolated historical patterns from a corpus of 21,367 scholarly articles using the topic modeling toolkit MALLET. Alternatively, I chose to analyze my 238 texts with a free Python library called Gensim and the LDAvis Python library (pyLDAvis). These packages worked together to examine the statistical recurrence of different topics within my corpus and to then display them through visualizations.

Furthermore, my project is indebted to my fabulous recently-graduated colleague Dr. Megan Kane and the excellent code she created for the Cli-Fi project which can be accessed via Github. My rendition of Megan’s code allowed me to break the texts in my corpus down into small chunks before trying to identify 100 topics present within those chunks.

Speaking the Unspeakable

So what did my topic model reveal? What did my gothic corpus “say”? After a good deal of trial and error working with Google Colab and different runtime options, I was able to generate topics for each quarter of my corpus and visualize those topics through Word Clouds and more technical intertopic distance map visualizations.

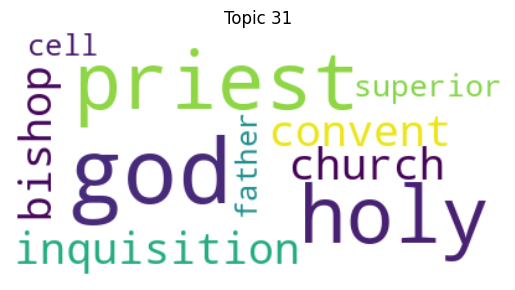

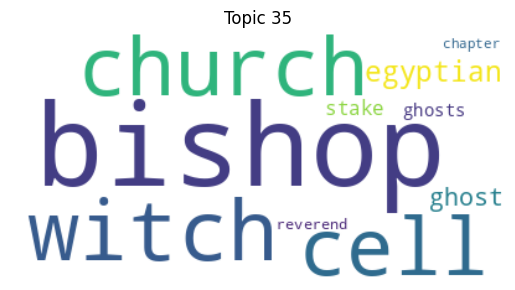

Although the results are not perfect, there are some focuses that clearly reoccur in different sections of the corpus such as Religion, depicted below in Topic 31 (1817-1890) and Topic 35 (1891-1903).

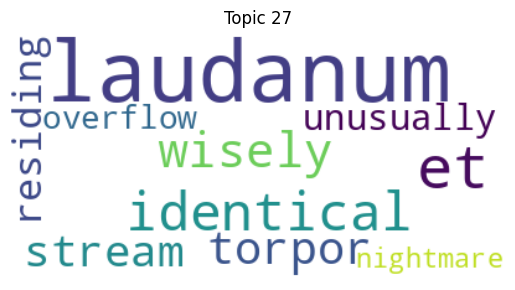

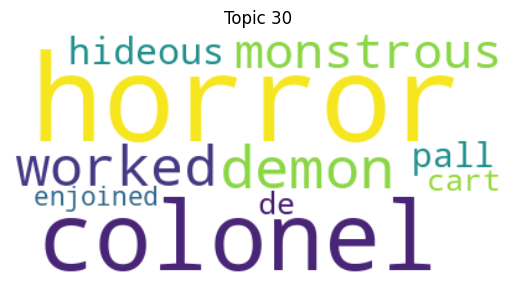

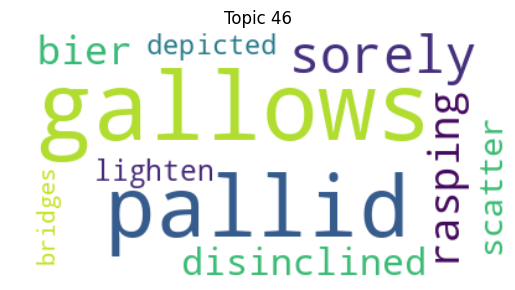

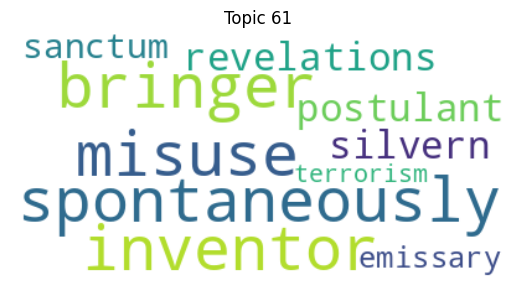

Of course, despite their consistent presence, the thematic focus of Religion (or Family, Nature, and House for example) do not seem unique to the gothic genre (though associating churches and bishops with witches and ghosts, as Topic 35 does, seems rather fitting). But I identified another topic that does seem to evoke my definition of the gothic, that which I have begun thinking of as “Unease/Insecurity.” We can see similar evocations of insecurity, vulnerability, and disintegration in representative topics from each quarter of the corpus: Topic 30 (1682-1816), Topic 27 (1817-1890), Topic 61 (1891 to 1903), and Topic 46 (1904-1925).

Conclusions

The presence of this recurring topic of gothic uneasiness, as well as the certain topics unique to each quarter of the corpus, such as the appearance of “chemical,” “magnetic,” and “evolution” in the 1904-1925 corpus alone, seem to confirm that topic modeling can be a helpful way to analyze genre changes or consistencies over time.

One can view the topics from each corpus quarter in relation to each other via the Intertopic Distance Maps hosted on my Github page: 1682 to 1816, 1817 to 1890, 1891 to 1903, and 1904 to 1925.

Although the topics and visualizations generated from my gothic corpus reveal that future projects would benefit from additional cleaning and consideration, the process of creating this gothic corpus, preparing it for topic modeling, and considering the results have given me greater insight into the world of late-17th to early-20th century gothic texts as well as how traditional and digital scholarly methods can work together to speak the unspeakable.

References

Baldick, Chris, ed. The Oxford Book of Gothic Tales, Oxford University Press, 1992, reissued 2009.

Goddu, Teresa. Gothic America: Narrative, History, and Nation, Columbia University Press, 1997.

Goldstone, Andrew and Ted Underwood. “The Quiet Transformations of Literary Studies: What Thirteen Thousand Scholars Could Tell Us.” New Literary History, vol. 45 no. 3, 2014, p. 359-384. Project MUSE, https://doi-org.libproxy.temple.edu/10.1353/nlh.2014.0025.

Hogle, Jerrold E. The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction, Cambridge University Press, 2002.