By Abby Corcelli

As part of the research team studying Book Banning in the Representation Lab at Temple’s Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio, our work focused on thinking through all aspects of how books are received by the public. With information accessibility at the center of the contemporary book-banning issue, we sought to collect and make available information on any and all aspects of the books being banned across the country in recent years, from info about publishers to graphical and textual content. After almost a full year of searching for, ordering, unboxing, dis-binding, and digitizing banned books, our collection of information is vast, amounting to thousands of rows of data on censorship today.

As a group of English literature students, you might imagine our research to involve poring over novels, with pens and highlighters in hand. You might think of us close-reading, analyzing, and making arguments about the language and narrative devices used in banned books. But actually, our project analyzing banned books covers hasn’t required us to read or even open banned books at all.

Creating a Dataset of Banned Books Covers

In previous pieces, SaraGrace Stefan and Sydney Grimm detailed our processes of exploring banned book covers with questions in mind about representation of characters and “objectionable” content or language. Through the process of documenting the features of these book covers, we looked at more than 1600 books and used a schema of tags to code the covers based on cover design, race and gender of depicted characters, language or keywords that could be deemed “objectionable,” and many other fields.

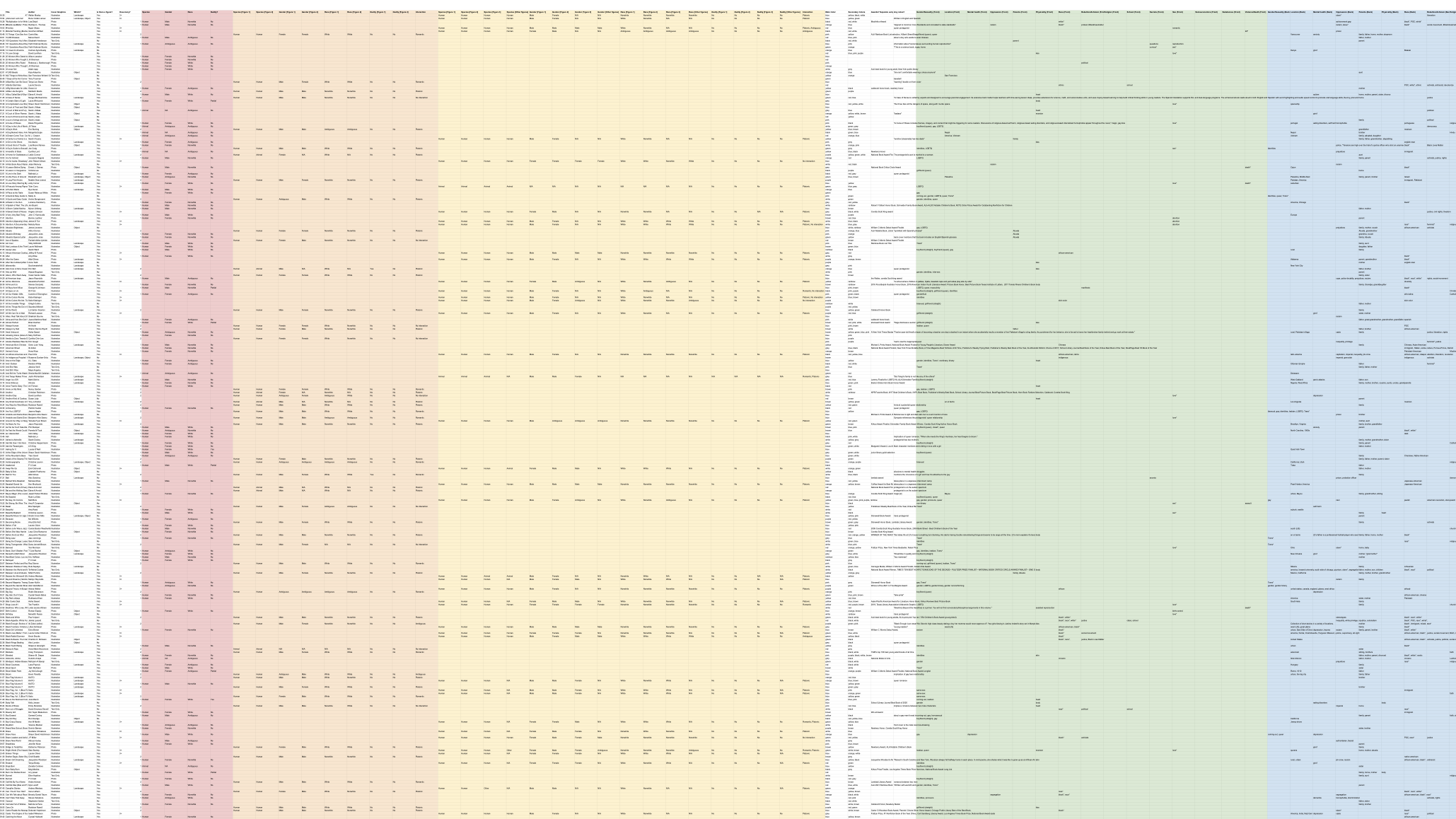

Throughout the process, we’ve documented and annotated each book with comprehensive metadata. But what is it that we actually have in our book cover dataset? And how might the information we’ve collected be used in future projects?

Our dataset has 9 general categories of data, all of which are collected into the large Google spreadsheet shown above. Each row of the spreadsheet corresponds to a single book in the Banned Books corpus and contains the following fields about their cover design and images:

- design type (illustration, photo, or text-only)

- subject (landscape/environment, object, or figure)

- race and gender of figures depicted

- nudity

- interactions between depicted characters

- primary design colors

- keywords on the front and back text

- book awards noted on the front or back cover

- and other noteworthy comments.

From an organizational standpoint, this data helps to reveal top-level information about our books and their content. If someone was, say, interested in looking at only the books in our set that feature female-presenting characters, this can be accomplished by referencing books that have been tagged with “figure” in the subject column and a “female” in the gender column.

From there, one could also zoom in to even more specific categories by looking at other tags. Exploring categories like race, multi-character interactions (romantic or platonic), or specific topic keyword tags helps to reveal interesting narratives about book banning and intersectional identities.

This book cover project also serves as a helpful starting point for the next phase of our project text mining the language used in the books.

Research Results: Uncovering Banned Book Covers

As described in previous pieces on this project, our methodology for analyzing covers involves interpretive judgments about characters and interactions in images. While we were intentional about standardizing this process as much as possible, we also recognized the limitations inherent in our subjective, qualitative decisions. Given that book banning, by nature, is inherently interpretive, we believe this data is representative and informative about our book corpus. And we’ve found that our results are consistent with the well-documented, contemporary phenomenon of book banning in interesting ways.

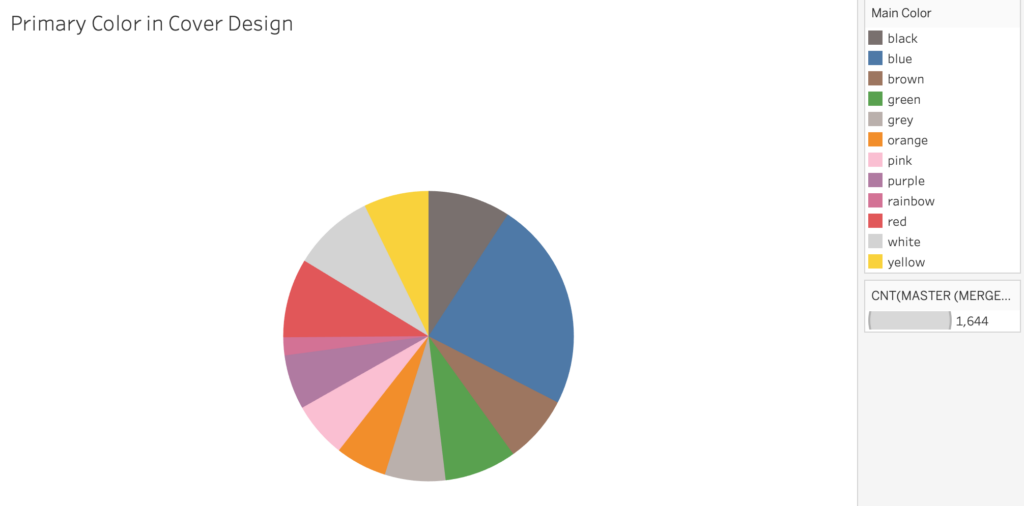

Color and Graphic Design:

We found that blue is the most common color among our cover data set, with 384 of our 1,651 books having primarily blue design elements.

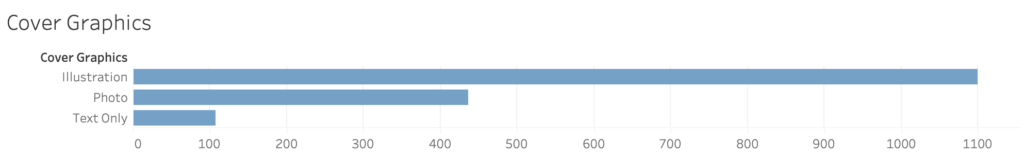

Additionally, a large majority of the covers feature illustrated graphic designs (1,100 or 66%), as compared to a much smaller proportion of photo and text-only designs.

Race and Gender:

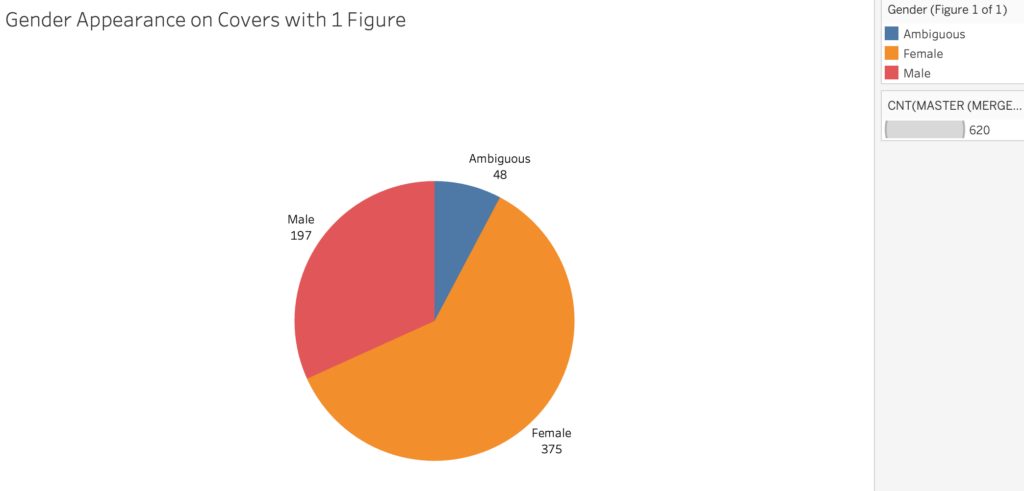

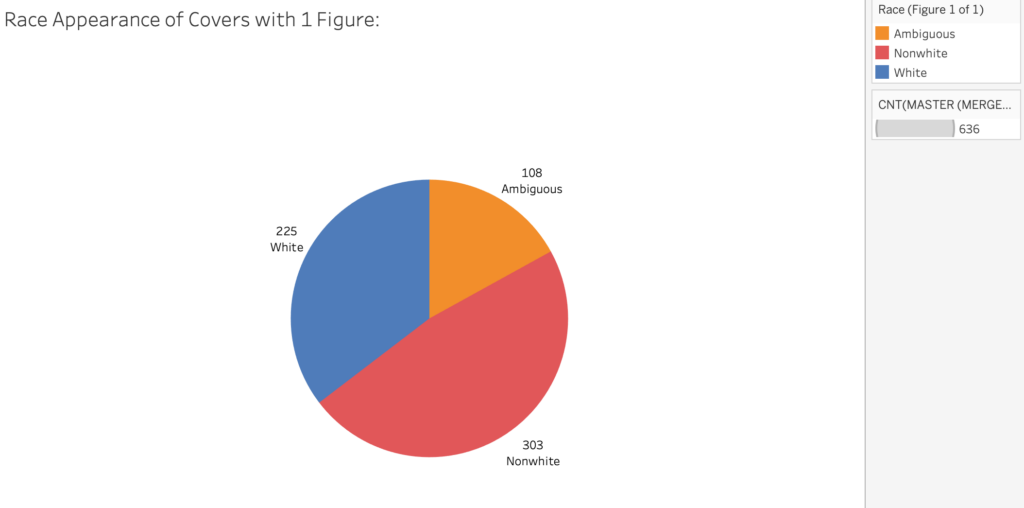

In terms of depicted characters, we found that 81% of the 1,651 book covers include at least one figure. Of the 620 books featuring exactly one figure, 375 (60%) of those figures appear female and 411 (64%) appear to be of nonwhite or ambiguous race.

Making Sense of the Data

The activist groups and individuals responsible for censorship of books in school classrooms and libraries are pretty forthcoming about their reasoning for challenging the content of these books. The “parental rights” organization Mom’s for Liberty is a well documented proponent of school book regulations, and they even circulate extensive guides that explicitly state their objections to books (often on the basis of gender, sexuality and race).

So, these findings on prevalent identities are likely unsurprising. However, the fact that the “objectionable” content is available before even opening a book may suggest that a book could be the subject of a potential ban without an opponent even reading it.

Because book covers are often the first piece of content a reader encounters when they engage with a book, this could suggest that the inclusion of specific racial, gender, or sexuality identities in a book’s cover design and marketing could contribute to its inclusion on a banned book list.

A Methodology to Replicate

In addition to exploring our own questions about book banning, we hope to have developed a methodology that can be applied to other corpora of published books to answer new research questions in different disciplinary fields. We found that analysis of visual images in the context of literature is a scarcely explored area, with few other projects modeling the kind of work we hoped to accomplish on character identity and representation.

Our process, then, became an amalgamation of different approaches, methods, and many, many iterations. We hope to have piloted a process that can be used to streamline other exploratory work on visual elements of books–including those like ours, looking at race, gender, or character interactions–or offer a model that could be adapted to examine other content areas.

Using data on book covers as a point of entry, we can further explore the relationship of a book’s cover design to its content, researching questions about how consistently book covers and their cover language accurately convey the content of a book. Do cover designs, marketing choices, and character illustrations accurately communicate relevant identities and topics to the content of the book? Could this factor into decisions to ban a book or book series?

The possibilities available in exploring and further applying our data and process are exciting to us, and we hope will be inspiring to others interested in book covers as interpretive representations of and framing for book content.

Works Cited

Moms For Liberty, “Book of Books Sampling.” Feb 3, 2023, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BNfax73kzqWwMMfkjcopgEXMDBD-fr4O/view

Hennessy, Paul. “Moms for Liberty Is Waging War on LGBTQ-Inclusive Books.” GLAAD, 3 November 2023, http://glaad.org/moms-for-liberty-book-bans-anti-lgbtq/. Accessed 1 March 2024.