By Tauheedah Asad

This second installment of this blog series for the Scholars Studio discusses popular working methods in digital cultural heritage work. These topics have been critical to creating my project The Diggin’ Philly Muslim Town Collection— a digital exploration of an American city with one of the highest concentrations of Black Muslims in the United States.

My previous post provides an overview of digital cultural heritage research; defining cultural heritage research and its significance. Here, I will begin by sharing the digital tools and methods used to create my project.

Digital Tools and Methods

Digital Archiving and Repositories

I recall a videographer I met when I first moved to the city. He’d recorded most of the significant events in the activist community, but those VHS tapes, photos, and CDs were stored in his basement collecting dust. This is the case with a lot of precious historical gems. They exist in private collections often living and dying with the individuals, often being tossed out once they’re no longer around.

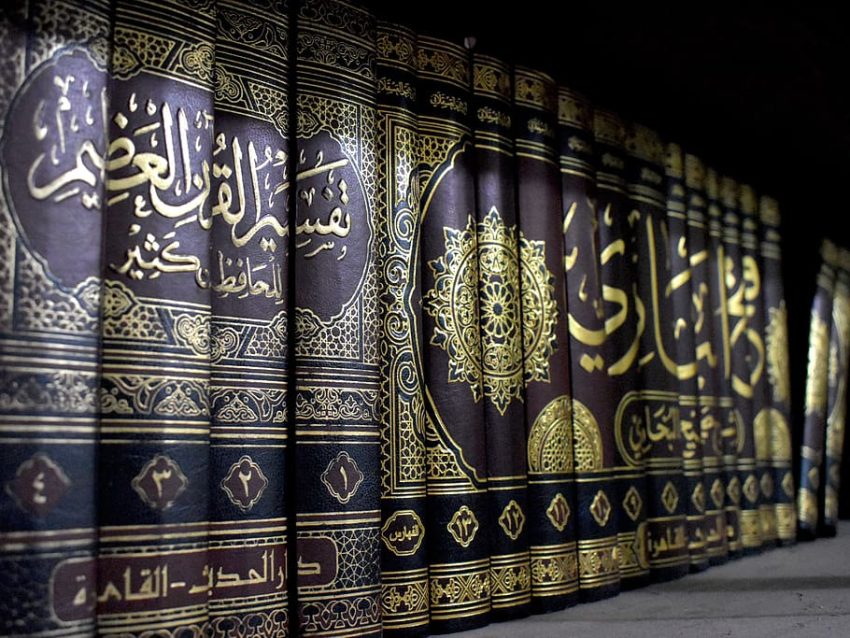

For this project, I built a digital repository featuring information on subjects and aspects of Black Muslim culture in Philadelphia. This component of the project includes descriptions and key information about the subjects, linked data, and a resource hub of popular and scholarly readings and other materials aggregated from the internet.

Digitization is an essential part of cultural preservation and information sharing in our current landscape. Digital preservation is “the active management of digital content over time to ensure ongoing access” (Library of Congress). Open-access systems such as Collective Access are useful for creating digital repositories and provide the ability to preserve cultural artifacts at no cost to the general public.

Interactive Mapping

Interactive mapping is a data visualization solution greatly favored in the field of digital humanities for the dissemination of geospatial data. Because of its increased popularity, the software options available are numerous. Last year, I shared my experiences trying out different tools as I created a map of historical markers in the city. In that post, I described the advantages and limitations of many of the popular tools.

In developing the “Muslim Town” collection, I used Google Earth’s mapping technology to create a virtual map identifying the spaces of worship established by Black Muslim communities in Philadelphia. What I liked most about Google Earth Voyager Projects is the ability to view 360° images of street view for each mapping point. Voyager also affords map creators the opportunity to tell their own stories by adding original descriptions and visuals. For my project, I captured 360° images of the most popular internal spaces of worship as a visual representation of their current spatial presence in the city. These images create many possibilities as spaces evolve and/or become endangered over time.

Timeline Visualization

Friends and family visiting Philadelphia often ask about the strong Islamic presence in Philadelphia. It’s truly unique. It’s not common for U.S.cities to have numerous people walking the streets in thobes and niqabs. And rarely will you find a U.S. city with Halal supermarkets and food options available on every corner, or mosques every few miles. How did this come about?

An effective way of displaying the evolution of Islam in the city is through timeline visualization. This digital tool helps make connections between key historical events and outcomes throughout the history of a community.

Open-source tools like timelineJS and Palladio enable researchers to create visually rich, interactive timelines for their projects using spreadsheets and free software.

I used this method to create a chronological sketch of the history of Islam in Philadelphia. The timeline shows how the Atlantic slave trade forced Africans from Muslim populations to the Delaware Valley during the era of settler colonialism. It then shows how events such as the rise of the Nation of Islam, changes in leadership among Islamic groups, and the establishment of institutions have contributed to the current culture of Islam in the city.

Oral Histories

Storytelling is a vital component of Black tradition and cultural heritage work. Stennett (2019) wrote:

With recollections of the past often told through idioms and long, enthralling storytelling, oral histories are the vessel between the present and the past, and in many ways act as a tool of cultural preservation.

Capturing the lived experiences of Black Muslims in Philadelphia has been the most gratifying part of this project. Not only do oral histories give us a sense of our history, but as a researcher, it informs us of what the audiences we serve find valuable. We’re able to learn areas of concern, and how we should move forward in our work. This creates a collaborative, co-creator relationship between researchers and participants that yield more substantive findings.

This portion of the research has been an opportunity for a wide range of individuals in the Black Muslim Community to share their introduction to Islam and experiences growing up in Philadelphia from various perspectives (e.g. experts, historians, journalists, and everyday people).

Conclusion

As the digital landscape continues to evolve so shall the technocultural affordances available to researchers doing cultural heritage work. It’s critical that we take the time to analyze these tools and methods, and consider how they can enhance our projects and share information with our intended audiences. Many of these digital tools are relatively easy to learn, inexpensive, and makes scholarship more accessible to the general public.