By Chau Nguyen

Intro

During my MFA in Painting at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture, I’ve embarked on a quest to incorporate Makerspace technologies into my art practice through fellowship research at the Scholars Studio. My work has traditionally emphasized the presence of the hand of the artist. By experimenting with emerging technologies for digital fabrication, I have translated this conceptual notion of the hand into a digital form in my project, “Traces of Tomorrow”.

“Traces of Tomorrow” contemplates the decolonization of Vietnamese commercial oil paintings. The project combines two elements: the mass production of copies of Western masterpieces in Asia and the current state of Vietnamese oil paintings.

Copies of Western paintings proliferate around Hanoi. I grew up seeing Vietnamese painting stores full of copies of famous Western paintings and iconic images.

A painting storefront in Hanoi, Vietnam

My project approaches the practice of oil painting as the point of colonial contact between Vietnam and the French in the 1920s. After the French’s introduction of oil painting to Vietnam, Vietnamese oil painting underwent further changes following the Vietnam War (1955-1975) and the subsequent influx of postwar Western tourism. One characteristic of current Vietnamese oil paintings that stands out through this history is the thick textures of the paint.

Textures of a van Gogh copy in Vietnam

Method

For my fellowship project, I am producing a series of 3-5 “paintings” through the creation of a transnational network and the use of digital fabrication technologies.

First, in the fall of 2021, I established a working relationship with a commercial painting store in Hanoi, whose paintings are then loaned to a 3D-scanning facility in Vietnam. The scanning service I use is 3DMaster Vietnam. I am working with a Hanoi gallery named Thế giới khung tranh Phú Mỹ.

After receiving the 3D models from Vietnam, I am working at the Scholars Studio Makerspace to use 3D printers and CNC machines to reproduce the scanned painting. So far I have successfully scanned 4 paintings from Vietnam and printed a resin slice composite, as well as a full-sized CNC copy.

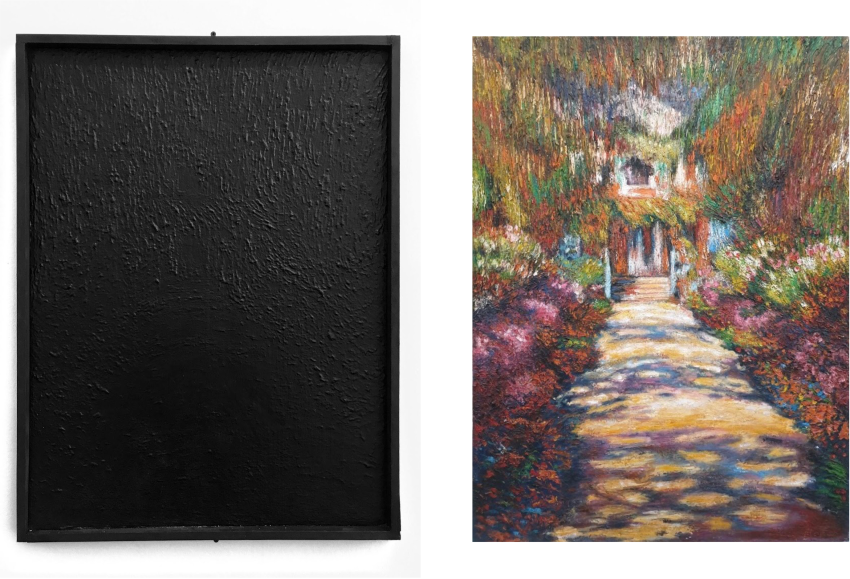

3D scan of a copy of a Monet painting sold in a painting store in Hanoi, Vietnam

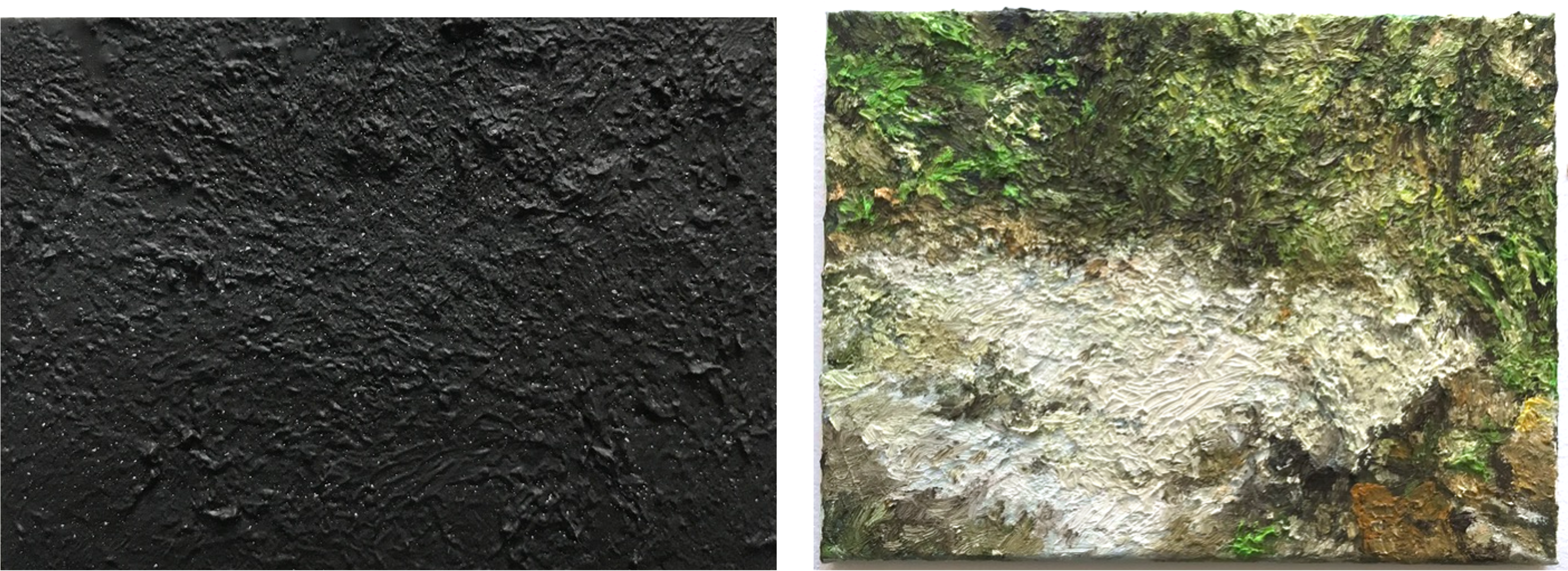

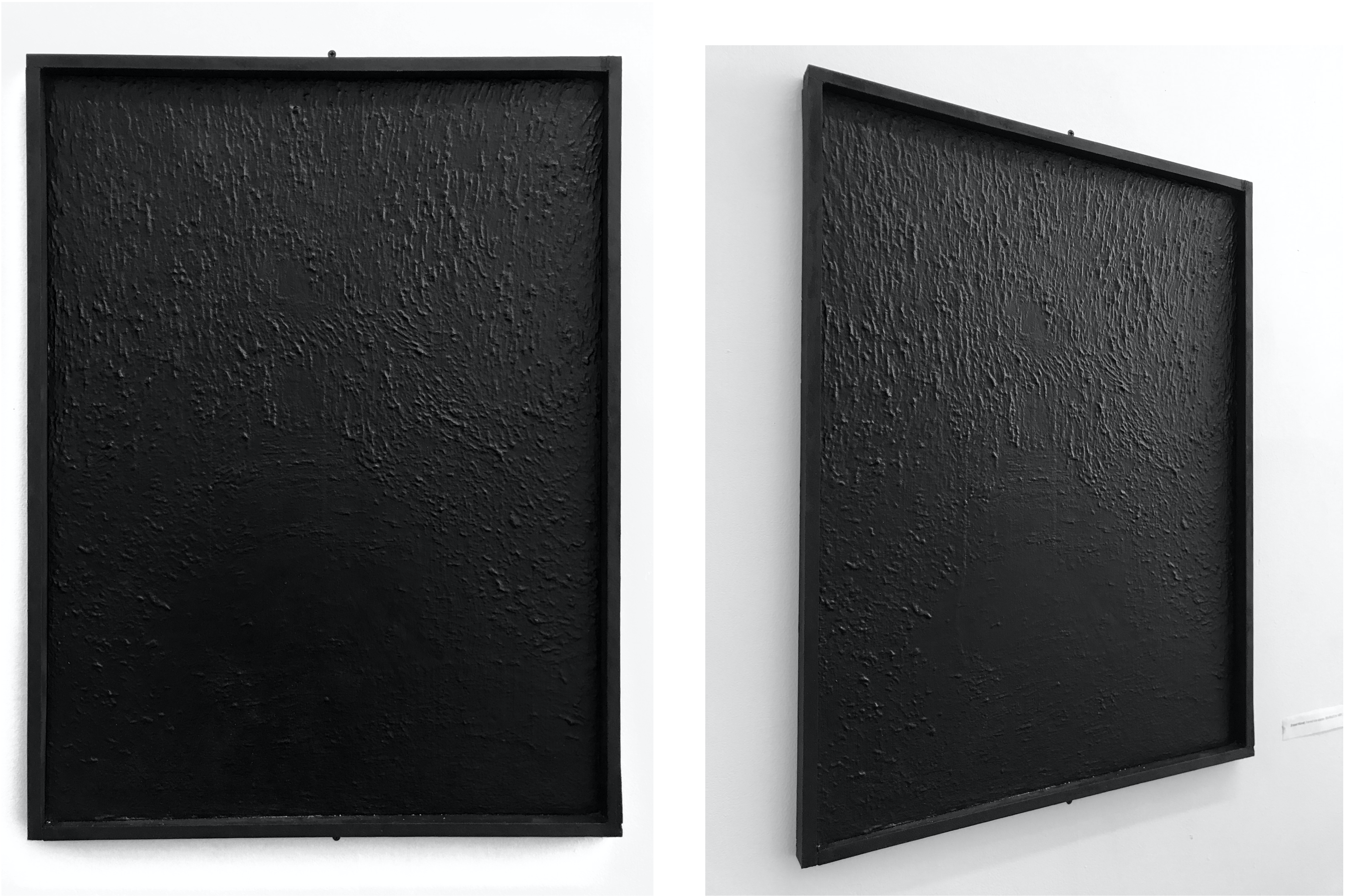

The works are printed in black, erasing the pictorial plane (the colonial influences) and leaving behind the traces of labor (the textures of the thick paint). The featured image is a side-by-side comparison of the final product and the physical painting in Vietnam. My conceptual decision aims to take away the impact of the Western gaze upon Vietnamese artists and give back agency to the Vietnamese artists whose labor went into the work. In this sense, I want to show that Vietnamese art has always existed under colonial and Western influences.

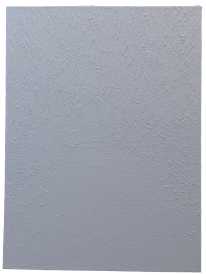

Textural comparison of a resin 3D print and original work (test)

This practice is geared toward the future, as I reimagine what painting can be through the radical gesture of pictorial erasure and digital fabrication.

First full-sized CNC machine work in MDF wood, approx. 30×24 in.

Significance

The project contemplates the decolonization of oil paintings in Vietnam. It suggests that contemporary Vietnamese art can exist and prosper within the acknowledgment of colonialism and the Vietnam War. I seek to shed light on an aspect of colonialism and of the unequal power paradigm between East and West that persists to this day through my bridging of Eastern and Western technology and makers.

The project introduces 3D scanning and printing technologies to Vietnamese art history, which has become more common in archival projects in the West but less so in Vietnam. My use of black connects the theme of decolonization in Vietnamese art with the aesthetics of a broader futuristic art practice seen in the work of artists such as David Hammons and Kazimir Malevich.

In the making of this project, I continuously went back to the idea of the digital archive and of the machine as a tool. What does it mean for me, as an artist of color, to maneuver the projected neutrality of technological tools to preserve and/ or critique certain aspects of my culture? To whom would this archive be accessible?

My will to subvert the secularism of painting as a Western-centric medium and the role of Western tourism in the landscape of Vietnamese painting is solidified into a conceptual gesture, but what kind of conversation can it initiate? With these questions in mind, I plan to create a small digital archive to expand the context of the work. Stay tuned for my next blog post for more.