By Elysia Petras

In this blog post I explore the potential of using the 3D modeling open source software Blender for historical archaeological research. I will detail how creating a 3D map in Blender of the 18-19th century plantation site, the Hughes Estate on Anguilla, became a methodology for exploring themes of power, control and resistance of the enslaved. This work informed my analysis of the plantation landscape; it also serves as a tool for visually representing marginalized historic narratives.

Project Background

The Hughes Estate was a moderate to large 18th- early 19th century sugar plantation on Anguilla. It is a uniquely well-preserved site for archaeological research as there has not been significant activity on the property since the 19th century. I spent my first season of research, summer 2019, surveying and mapping the property. Mapping was an important project goal, as the extent and number of structures on the site was initially unclear. Modern satellite technology has been ineffective in documenting the site since the majority of the plantation-era structures have been reduced to foundations, and as such are not easily visible due to dense overgrowth. Additionally, there are no known historic maps of Hughes Estate nor of any Anguillan plantation in existence.

At first the lack of historic maps was surprising, as imperial powers produced maps to control both the economic, political and social life of their overseas Caribbean colonies (Armstrong et al 2009). However, the English did not expend effort to officially map Anguilla as it produced little wealth for the imperial core. This relationship is clear in a 17th century account of Anguilla by the Governor of the Leeward Islands “…being never surveyed, there can be no account given, neither is it material, being fitter for to raise stocks of cattle than to yield any great produce of sugar…”(Stapleton 1676). Due to the continued unprofitability of the colony for England, Anguilla was able to evade larger oversight and function without a legally constituted government until 1825 (Mitchell 2021), and remain unsurveyed until as late as 1972 (McKinney 2002).

Mapping Hughes Estate

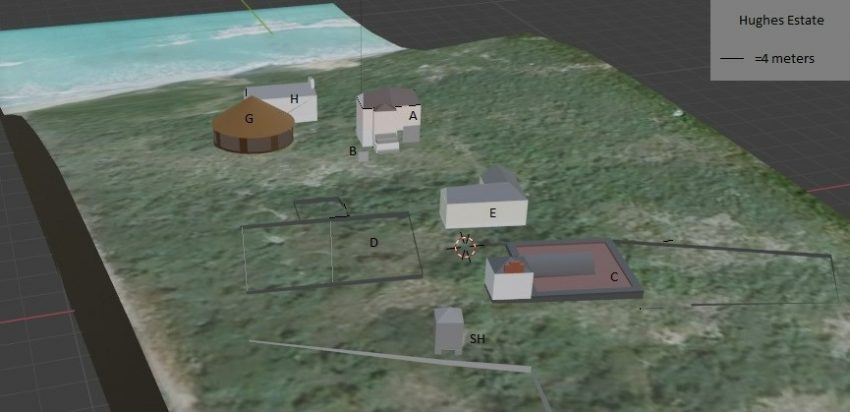

During summer 2019 the mapping crew, consisting of myself, Temple University undergraduate students, and an Anguillan Intern, located and mapped nine structures and two field walls, establishing Hughes as the most extensive 18-19th century plantation site remaining on Anguilla. We took measurements with a surveying compass and stadia rod and drafted the map by hand, which was later cleaned up in illustrator by crew member Cara Tercsak (figure 2).

Creating a 3D Map of the Hughes Estate in Blender

Unable to return to Anguilla for the 2020 fieldwork season due to the global pandemic, I focused my efforts on building a project website to share my preliminary research results and invite engagement with the project. I created at 3D model of the site in Blender to display on the website, and in the process of doing so found it to be a useful methodology for generating new research questions and analysis.

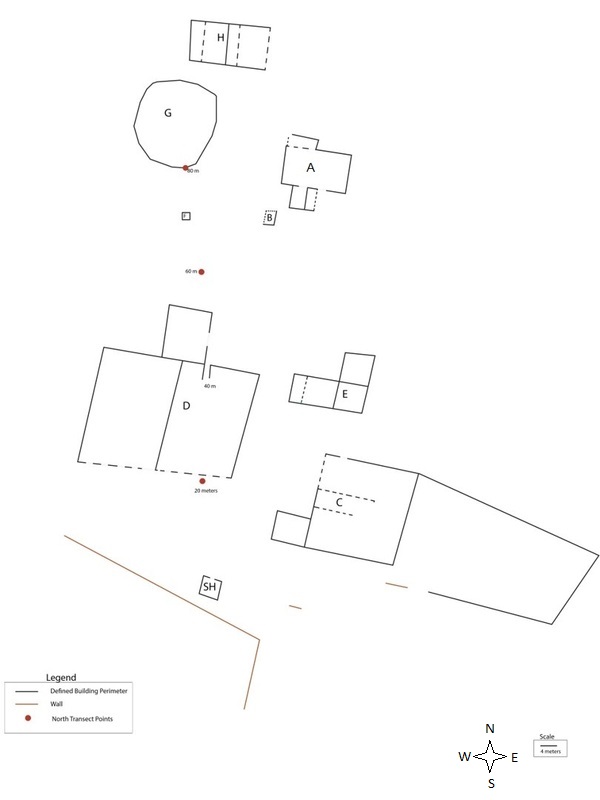

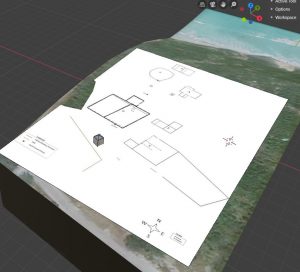

To create a 3D map of the Hughes Estate site, I used Blender and downloaded the GIS add-on. The GIS add-on enables the user to pull up a world map on Blender and zoom into and crop selections. The initial selection is a 2D image, but with the “Get Elevation (STRM)” feature, users are able to add accurate elevation data to the map, creating a 3D model of the terrain. If geometry data for buildings have already been created for the map area, 3D buildings can be added as well. No geometry data existed for my site, but I was able to add elevation data.

I added a jpeg of the 2D map I had drafted as a layer to my Blender file. The Smokehouse building is the only intact structure remaining on the site, and as such is the only structure to appear on satellite imagery. I lined up the blueprint of the smokehouse from my 2D map with the satellite footprint. I then scaled and rotated my map to line up with the site accordingly. I then created 3D models of each site structure over my map. When I was done creating each structure over the map blueprint, I deleted my map layer, leaving the structures on the 3D terrain of the site.

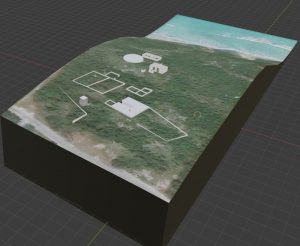

The resulting model was an improvement from the 2D map, as 3D topographic data provides context for how the structures relate to the geography of the site. Additionally, the 3D adds the dimension of height, while 2D maps can only display length and width. Photographs of the structures also fail to capture the same contextual data as the 3D model. For example, the relationships of structures to one another or to the larger landscape are not visible in photographs or even in person due to the current dense overgrowth, but these become clear in the 3D model.

3D Modeling as a Methodology in Landscape Archaeology

My interest in plantation layout is in the tradition of studies that focus on power relations encoded in the landscape (Armstrong and Kelly 2000; Delle 2011). Study of the layout of Hughes Estate can reveal strategically designed “geographies of power” (Delle 2011) which shaped the daily struggles of the enslaved. In order to visualizes viewsheds of surveillance (Delle 2011) on Hughes Estate, I made a new Blender file in which I recreated the historic structures based on photographs of Caribbean and Anguillan plantation era architecture.

In the process of imagining and building the historic structures in Blender, new questions emerged. For example, I initially thought that Structure B may have been an outdoor oven loosely connected with Structure A, but I am now exploring the possibility of B as an attached Staircase to A. Additionally, I began to contemplate the position of doors and windows as well as structure materials. Through the analysis of artifacts, I will strive to learn more about building materials and architecture.

Decentering Dominant Visual Representations of Slavery

The historic reconstruction of Hughes Estate also enabled me to create better online representations of the site and center marginalized figures. To decenter the dominant narratives of the plantation owners and re-center black perspectives in heritage representations of the plantation, Flewellen asks: “What would the house slave see? How would the house slaves, male or female, interpret the space around them… What would a display board look like that oriented visitors to this interpretation?” (Flewellen 2017).

The 3D model I created helped me keep the narratives of the enslaved at the center in my discussion of the main estate house. In addition to being the residence of the plantation owners, enslaved domestic workers also spent time and perhaps even lived in that structure. The 3D recreation enabled me to illustrate how the enslaved workers may have viewed this space by providing a visual of the relationship of the main estate to the ocean. The inclusion of the model angled to show this view complimented my description of how domestic workers who labored in the main estate house might have perceived the landscape.

To the enslaved domestic workers, the sea may have represented a connection to a wider and better world. Perhaps looking at the ocean reminded them of community members who had self-liberated by escaping British Anguilla by sea to nearby French St. Martin.

Future Directions

I will continue to update the virtual recreation as I gain new data. In the immediate future, I plan to create a 3D model of the smokehouse through photogrammetry. As the smokehouse is the only intact structure at the site, it is also the only structure that does not benefit from a 3D recreation in Blender. I will import the new 3D model made from photographs into blender to replace the current version of the smokehouse. Capturing the smokehouse in 3D through photogrammetry will be a valuable preservation practice. In response to the damage caused by recent hurricanes to structures related to Afro-Caribbean heritage, the Society of Black Archaeologists call for capturing the visual and structural information that is usually missing from standard archaeological reports (Dunnavant et al 2018). I believe that photogrammetry can be an ideal tool to be employed by heritage workers for architectural preservation.

My hope is that the 3D model of Hughes Estate, and the narratives it brings to life will be an engaging aspect of my website. Haviser, an archaeologist working in Dutch St. Maarten found that artifacts fail to engage audiences in the same way as presenting narratives of the past from the perspective of a historical figure(Haviser 2015). A goal of my website is to develop community engagement with every aspect of my research project from planning to execution, to interpretation and representation. The integration of new media such as 3D models may increase the involvement of community members who would not be traditionally interested in archaeology. It offers another channel for project involvement and skill building.

Works Cited

Armstrong, D.V. and K.G. Kelly

2000 Settlement Patterns and the Origins of African Jamaican Society: Seville Plantation, St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica. Ethnohistory 47(2):369–397.

Armstrong, D.V., M. Hauser, D.W. Knight, and S. Lenik

2009 Variation in Venues of Slavery and Freedom: Interpreting the Late Eighteenth-Century Cultural Landscape of St. John, Danish West Indies Using an Archaeological GIS. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 13:94-111.

Delle, J. A.

2011 The Habitus of Jamaican Plantation Landscapes. In Jamaica In Out of Many, One People: the Historical Archaeology of Colonial Jamaica, edited by J.A. Delle, M.W Hauser and D. Armstrong, pp 99-113. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Dunnavant, J.P., A.O. Flewellen, A. Jones, A. Odewale, and W. White

2018 Assessing Heritage Resources in St. Croix Post‐Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Transforming Anthropology, 26(2):157-172.

Flewellen, A.O.

2017 Locating Marginalized Historical Narratives at Kingsley Plantation. Historical Archaeology 51:71–87.

Haviser, J.B.

2015 Truth and Reconciliation: Transforming Public Archaeology with African Descendant Voices in the Dutch Caribbean. Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage, 4(3):243-259

Higman, B.W.

1984 Slave Populations of the British Caribbean 1807-1834. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

McKinney, J.D.

2002 Anguilla and the Art of Resistance. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of American Studies, College of William and Mary, Virginia.

Mitchell, D.

Anguilla from the Archives Series. Anguilla Archaeological and Historical Society. Accessed March 2021. https://www.aahsanguilla.com/don-mitchell-cbe-qc.html

Stapleton, W.

1676 Stapleton on Conditions in Anguilla 1676. Records of the Colonial Office, CO 153.2. National Archives, Kew, England.