By Eugene Kukshinov

Introduction

As a part of my digital project at the Scholars studio, I am working with Dr. W. Geoffrey Wright, the director of the Motion-Action-Perception Laboratory, or MAP lab, to develop virtual environments via Unity 3D to create a virtual reality (VR) application for behaviorally measuring the sense of presence in VR. Presence is defined as a perceptual illusion of non-mediation/non-simulation which allows us to gain real experience from simulated contexts. In the end, this VR app should be:

- A validated measure of presence

- Accessible to VR researchers and practitioners

- A significant resource in increasing replicability of presence research

Existing behavioral measures

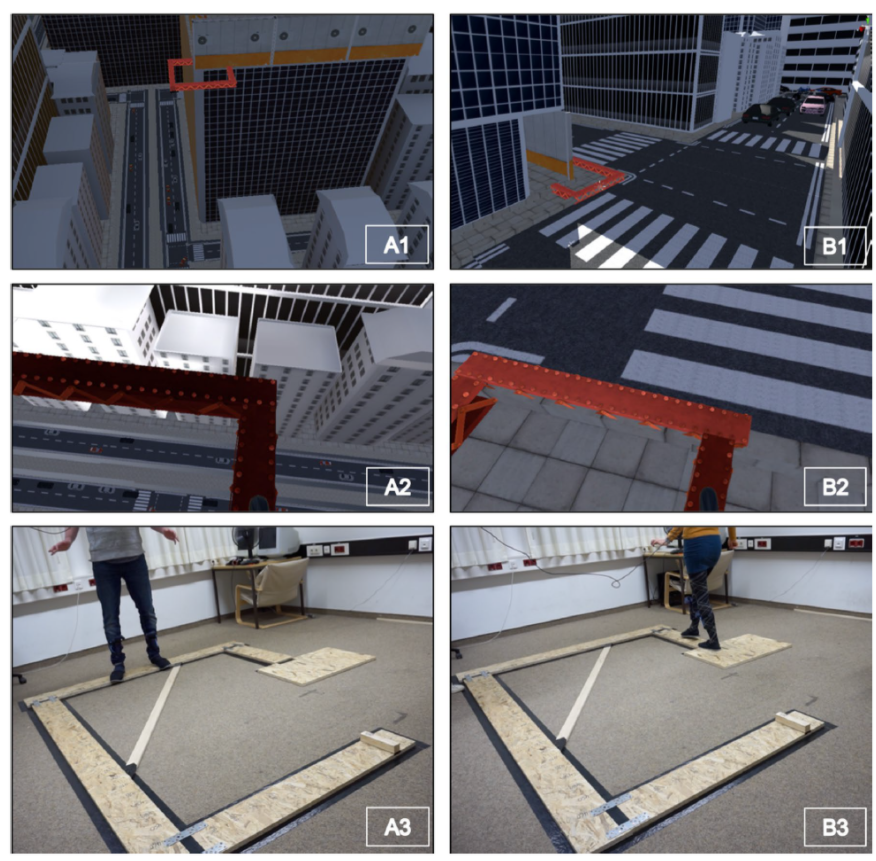

There is no systemic way to measure presence behaviorally. There are only a few studies that use their own VEs to measure presence via behavioral reactions, such as bending (over virtual trees), head moving (Slater, McCarthy & Maringelli, 1998), postural change (Freeman, Avons, Meddis, Pearson, & IJsselsteijn, 2000) or “swaying in response to a moving visual field, or ducking in response to a flying object” (Slater, 2004, p 486).

As a motivation to act/perform in the Virtual Environment (VE), sometimes VR users are given tasks (Slater, McCarthy & Maringelli, 1998) and then their virtual behavior is processed into data and analyzed. Most of the time, fear is the major motivator. For instance, in height experiments, one study tracks the pace of walking (see Figure 1) through the plank segments (Kisker, Gruber, & Schöne, 2019).

Figure 1.

Another study (Figure 2) observes what kind of “pit-avoidance” behaviors would be exhibited. Such behaviors included: taking careful baby-steps, leaning away from the pit toward the walls, testing the edge of the ledge with a foot, etc” (Insko, 2003, p.113).

Figure 2.

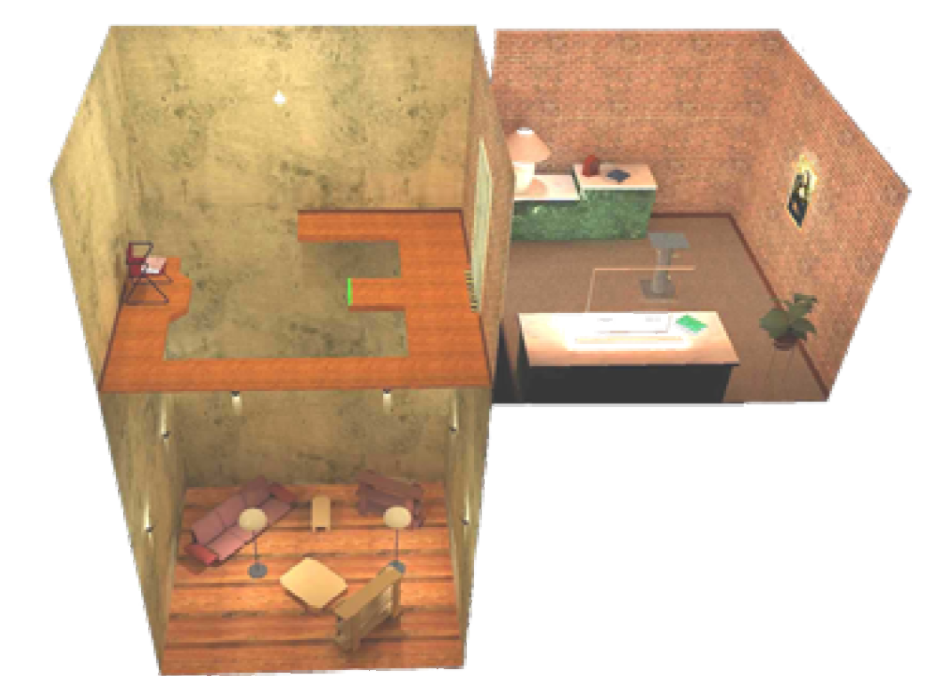

In a much more diversified approach, scholars (Malbos, Rapee, & Kavakli, 2012) created 4 different threatening situations (such as a shark attack or a room caught in fire, see Figure 3). Then, they described and measured various types of behavior exhibited by participants, including basic steps, for how long they freezed, avoided something, how many times users looked at the threat, and so on. But, in designing virtual measures, it is fair to say that “the more simple and discrete the actions are, the more reliable and accurate the observations will be” (Laarni et al. 2015, p.158).

Figure 3.

My project

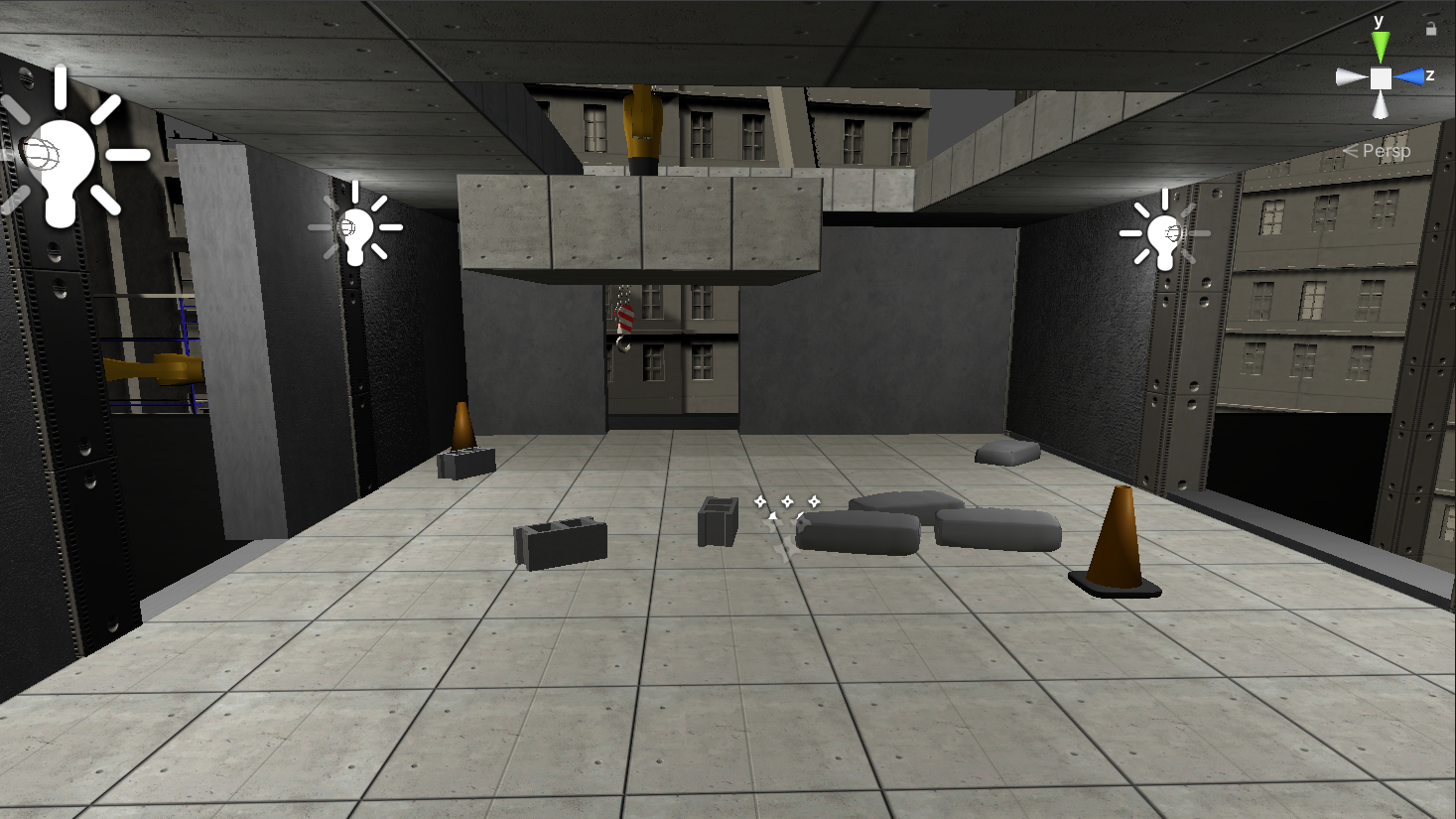

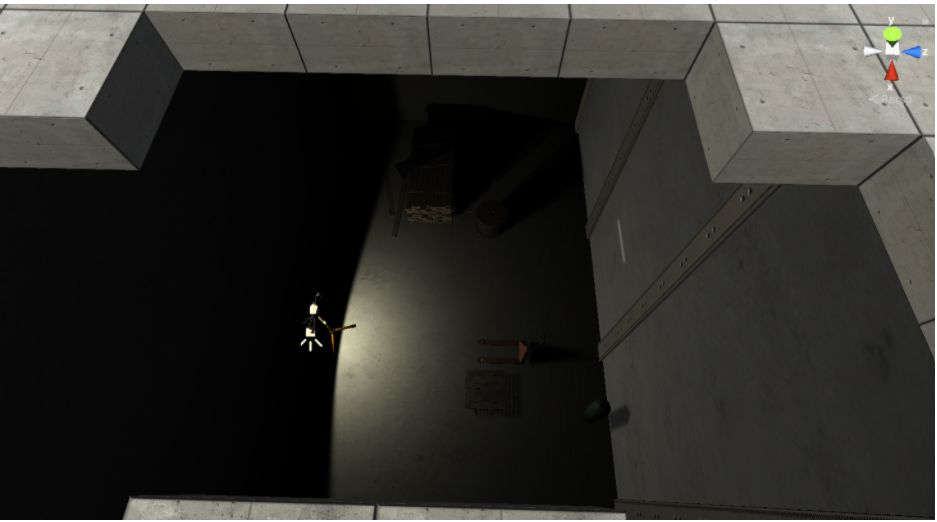

To build upon this research, I am currently designing the main VE via Unity, which is a room located in the building under (de)construction (see Figure 4). The VE includes moving objects, or, specifically, elements of the walls, ceiling, and floor. When approaching the VR user closely, these elements are supposed to stimulate a behavioral response. This reaction is easily measured by tracking because it is based on simple postural change along a single axis. At the same time, the room, in the end, will become a stand with a pit (see Figure 5) which will also stimulate a behavioral response.

Figure 4. Screenshot of the Unity scene in development

Figure 5. Screenshot of the Unity scene in development (2)

I am trying to make the VE as realistic as possible because realisticness is one of the variables that will be tested during the validation of the measure. For this reason, I looked for detailed materials, existing 3D models such as surrounding buildings, a crane, robot arms (that supposedly move the room elements), and other objects. I found them both in the Unity Asset Store and other free online sources. At the same time, I tried to fill in the scene with (spatialized) sounds relevant to the construction site. And, despite animating the room elements, there is also an animated crane in the background. Once the realistic VE is done, I will remake it (visually) into a non-realistic space, which can be a sci-fi space station or something else completely.

There are still many things that I still need to do before the VE(s) can be tested, i.e. conducting the experiment with participants to validate the measurement. First, I need to understand which sequence of the room elements will be fully noticed by each user. Second, I need to finish the animation and decide on each stimulus. After that, I will need to incorporate scripts for collecting tracking data, and for the UI, i.e. the interface of the app (when it is already tested). After all is done, I hope this app will become a standardized, accessible, and reliable measure that will be used by presence researchers to conduct their studies.

References:

Malbos, E., Rapee, R. M., & Kavakli, M. (2012). Behavioral presence test in threatening virtual environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 21(3), 268-280.

Kisker, J., Gruber, T., & Schöne, B. (2019). Behavioral realism and lifelike psychophysiological responses in virtual reality by the example of a height exposure. Psychological Research, 1-14.

Insko (2003) Measuring Presence: Subjective, Behavioral and Physiological Methods. In Riva, G., Davide, F., & IJsselsteijn, W. A. Being there: Concepts, effects and measurement of user presence in synthetic environments, pp.110-118.

Slater, M., McCarthy, J., & Maringelli, F. (1998). The influence of body movement on subjective presence in virtual environments. Human factors, 40(3), 469-477.

Freeman, J., Avons, S. E., Meddis, R., Pearson, D. E., & IJsselsteijn, W. (2000). Using behavioral realism to estimate presence: A study of the utility of postural responses to motion stimuli. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments, 9(2), 149-164.

IJsselsteijn, W. A., De Ridder, H., Freeman, J., & Avons, S. E. (2000, June). Presence: concept, determinants, and measurement. In Human vision and electronic imaging V (Vol. 3959, pp. 520-529). International Society for Optics and Photonics.

Laarni, J., Ravaja, N., Saari, T., Böcking, S., Hartmann, T., & Schramm, H. (2015). Ways to measure spatial presence: Review and future directions. In Immersed in Media (pp. 139-185). Springer, Cham.

Slater, M. (2004). How colorful was your day? Why questionnaires cannot assess presence in virtual environments. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments, 13(4), 484-493