By Ania Korsunska

No doubt you know from your own experience, misinformation about scientific studies is abundant and often these types of stories spread like wildfire throughout social media and other networks. But, is “wild fire” the right metaphor? A group of information science scholars recently have been asking such questions.

What if information spreads like a virus?

“Virus” is an interesting concept. On one hand- it’s defined as an infective agent that is able to multiply within the living cells of a host. On the other hand – it colloquially refers to a piece of code that is capable of copying itself and having a detrimental effect on a computer system. We don’t think of viruses as associated with anything positive, like a cat playing the piano. But it’s not the bacteria or code itself that makes something a “virus”, but it’s the mechanism of spread that is its defining feature.

Luckily, virus spread networks existed much longer than the internet, so researchers have a unique insight into how these mechanisms work. The video below is an amazing, unique illustration of this. It’s from the Kishony Lab at Harvard Medical School, and it illustrates how bacteria move as they become resistant to antibiotics.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=plVk4NVIUh8&w=900&h=506]

Each section contains higher and higher doses of antibiotics and in the video you can see how over time, the E. coli bacteria – fascinatingly and terrifyingly – learns to adapt to survive in them. The ending image shows the network of the spread and evolution of the bacteria, making obscure concepts such as mutation and viral spread intensely visual.

Viral Spread Networks

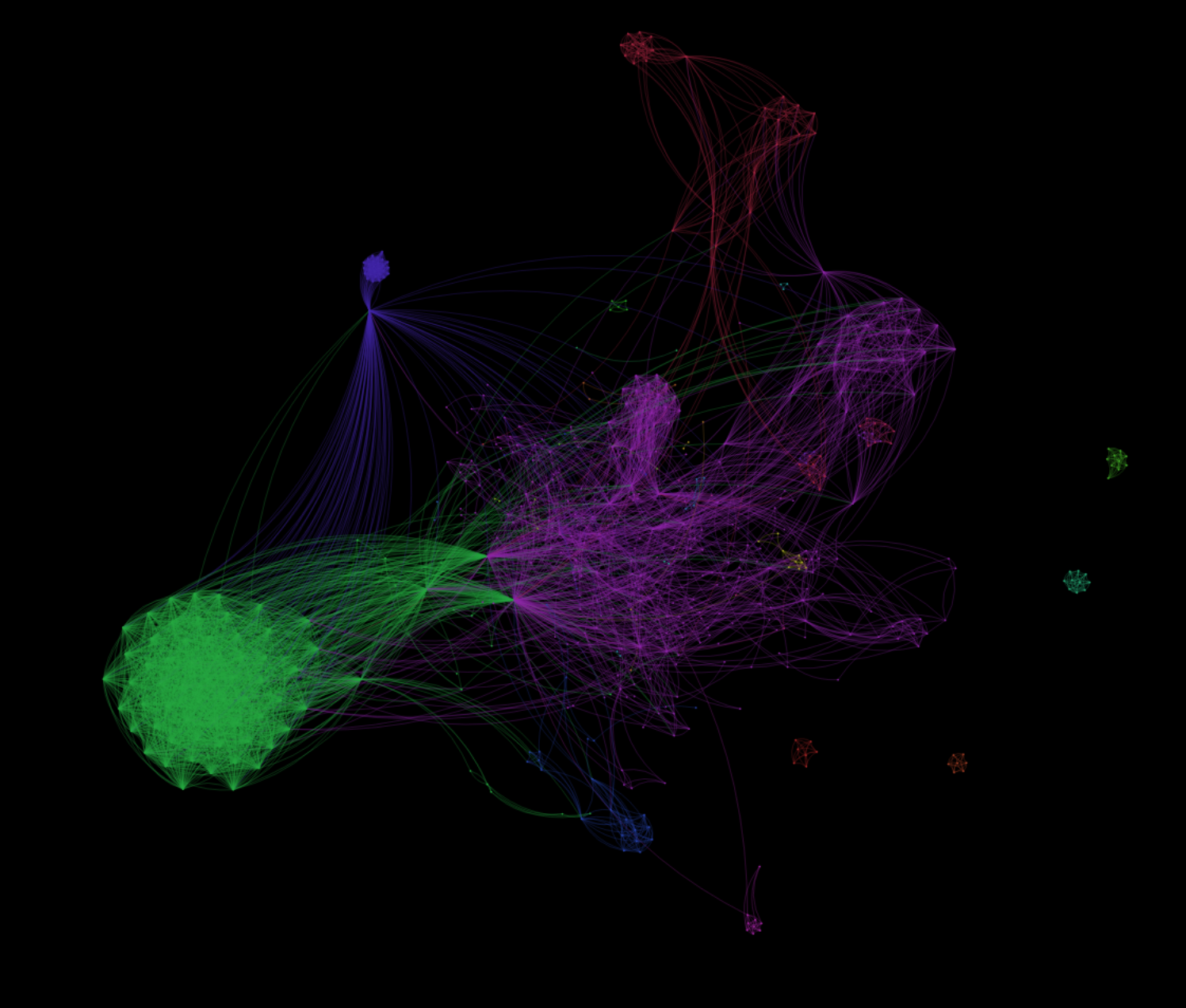

Though far from the medical field myself, I have a fascination with networks. Luckily, this notion of “viral” spread in not only in the medical field, but is now also connected to things like funny cat videos and abuse of passengers on airplanes. The underlying mechanisms seem to be similar: some information – be it genetic information or a cat playing the piano – is passed along to other locations, where the spread continues rapidly through sharing.

The question is then, how can we use research methods such as network analysis to study media information spread? What kind of information is more likely to travel like a virus, and is that the same as something “going viral”?

Dr. Karine Nahon (University of Washington, iSchool) and Dr. Jeff Hemsley (Syracuse University, iSchool) wrote a book Going Viral, where they thought about what the concept of “virality” entails:

“Virality is a social information flow process where many people simultaneously forward a specific information item, over a short period of time, within their social networks, and where the message spreads beyond their own [social] networks to different, often distant networks, resulting in a sharp acceleration in the number of people who are exposed to the message” (Nahon & Hemsley, 2013).

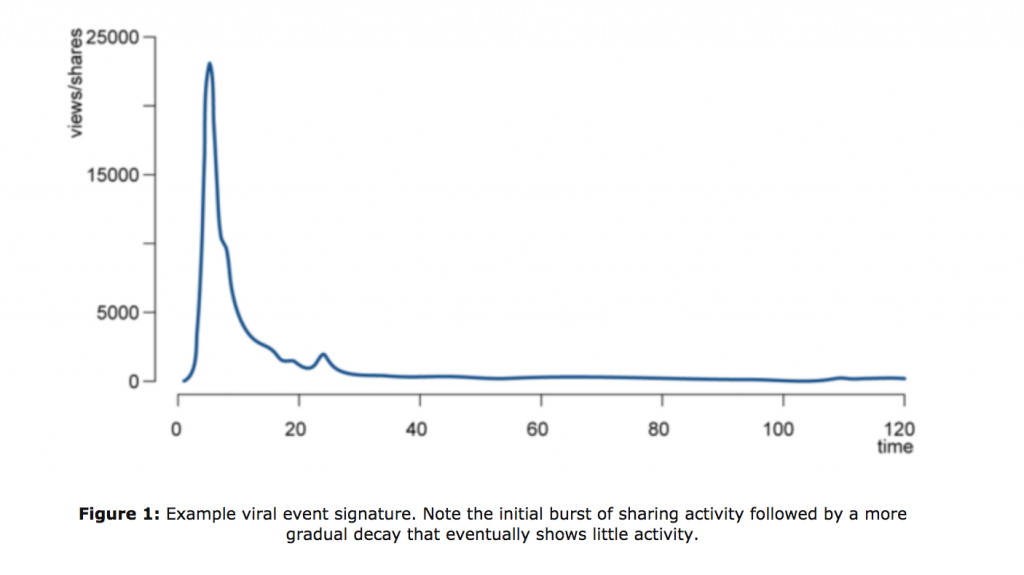

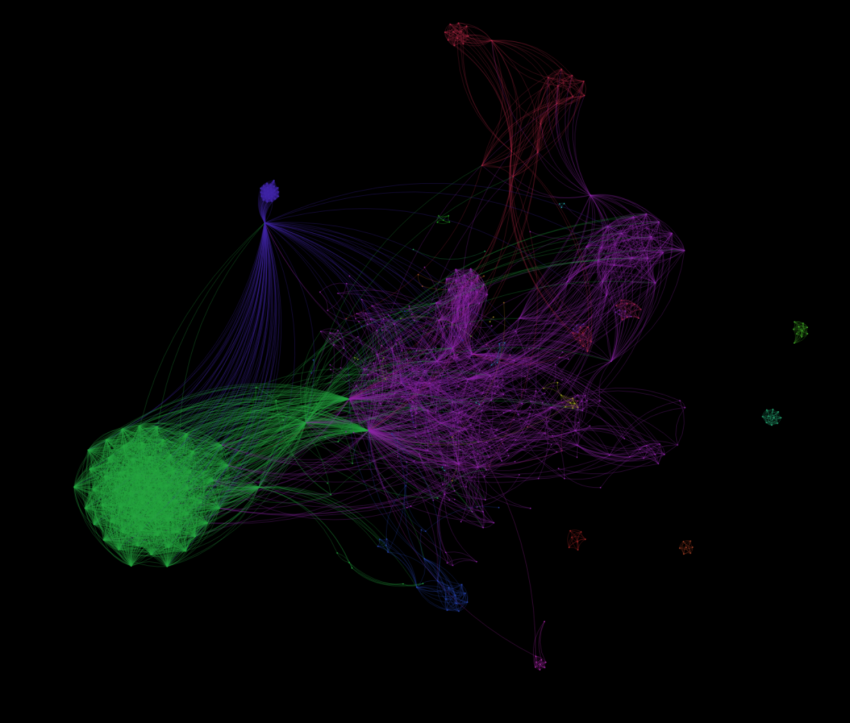

Key to this concept is the unique signature (see visual below) that viral events have in common, illustrating a sharp, fast increase in sharing activity that spans across any sort of barrier (such as media sources, social networks, friend groups, countries, etc.)

If we look at viral information as a disease that spreads from person to person, it opens up some interesting opportunities for network analysis. For example, some recent computational studies are currently looking into viral spread of memes, and show that some tend to spread like epidemics in between social networks (Weng, Menczer, & Ahn, 2013). And the metaphor of “epidemic” seems accurate, since misinformation that goes viral can also have lasting, negative effect on people’s lives, especially misinformation related to health, science and medicine.

Research also has shown that, though fact-checking and corrections exist, misinformation has also been shown to spread much faster and wider than the truth (Vosoughi, Roy, & Aral, 2018), and be very difficult to eliminate from people’s minds, even after being debunked (Hochschild & Einstein, 2015; Nyhan & Reifler, 2015). This means that, once infected, both entertaining information and harmful misinformation leaves a mark and shapes our worldview, possibly affecting our future behavior.

Hopefully as researchers, myself included, continue to explore this new, innovative space, we can find the “antidote” or “vaccine” to protect ourselves from being consistently exposed to viral misinformation.

References

Nahon, K., & Hemsley, J. (2013). Going viral. Polity.

Hemsley, J. (2016). Studying the viral growth of a connective action network using information event signatures. First Monday, 21(8).

Hochschild, J. L., & Einstein, K. L. (2015). Do facts matter? Information and misinformation in american politics, Political Science Quarterly, 130(4), 585-624.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2015). Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine, 33(3), 459-464.

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151.

Weng, L., Menczer, F., & Ahn, Y. Y. (2013). Virality prediction and community structure in social networks. Scientific reports, 3, 2522.

All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could fix if you weren’t too busy looking for attention. Spot on with this write-up, I truly think this website needs much more consideration. I’ll probably be again to read much more, thanks for that information.