By Caroline Tynan

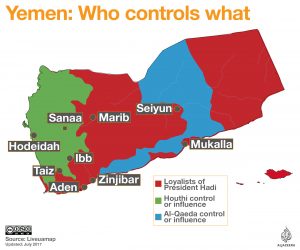

It is far beyond the scope of this blog to adequately cover the complexities of the current conflict in Yemen. I focus here on the movement for southern secession, and the potential manipulation of social media by external regional actors as part of their own self-serving agendas. Western media have followed the Saudi-led sectarian narrative on its current intervention in Yemen, portraying it as a proxy conflict of ‘Iranian-backed, Shi’a’ Houthi militias from the north versus a Saudi-led Sunni Arab coalition. This, despite historic Saudi alliances with Zaydi Shi’a leaders in northern Yemen, not to mention the significant theological differences between the Zaydi Houthis and the more mainstream Twelver Shi’ism of Iran. Southern Yemeni activists have, like those supporting Houthis in the north, been incited to protest against the failings of the Saudi-initiated 2011 transition process in Yemen that failed to sufficiently address any of their longstanding grievances. Likewise, the impetus for southern secession goes back decades. The 1994 civil war that saw Saudi support for President Saleh’s repression of southern separatist forces occurred after just four years of a unified Yemeni state. Marginalization under Saleh’s rule has radicalized currents within both the southern al-Hirak movement and those supporting the northern Houthi movement, with al-Hirak’s calls for secession emerging as early as 2009. The failures of the National Dialogue Conference in 2013-14 ended any potential for compromise among these aggrieved groups, only further entrenching dissatisfaction as well as divisions among those who had opposed Saleh’s regime.

Context: 2011 Yemeni uprisings

After a diverse coalition of activists, including the long-marginalized Houthis in the north and the broad southern secessionist movement known as al-Hirak, came together to oust President Saleh in 2011, Saudi Arabia, alongside its monarchical counterparts in the Gulf Cooperation Council, swooped in to facilitate the transition of power to Vice President Hadi and initiate a National Dialogue Conference and political transition . Despite being a massive failure in the eyes of al-Hirak, the Houthis, and the majority of Yemenis who had taken to the street en masse in 2011, Saudi Arabia exploited the international community’s support for its GCC Initiative and corresponding NDC to proclaim to both its people and the international stage ‘legitimacy’ for the massive military intervention it began against the Houthis on March, 26, 2015. In fact, it was the failure of the GCC Initiative to respond to grievances in the north and south alike that strengthened the Houthis’ political and military support in the north, setting the stage for their ability to take the capital and then descend upon Taiz and Aden in the south. Many southern activists in al-Hirak came to be torn between fears of northern expansion by the Houthis and distrust of President Hadi and his backers in Riyadh. In the meantime, the Saudi-led military offensive Operation Decisive Storm/Renewal of Hope has over the past 2.5 years culminated in the world’s largest humanitarian crisis.

South Arabia Tweets

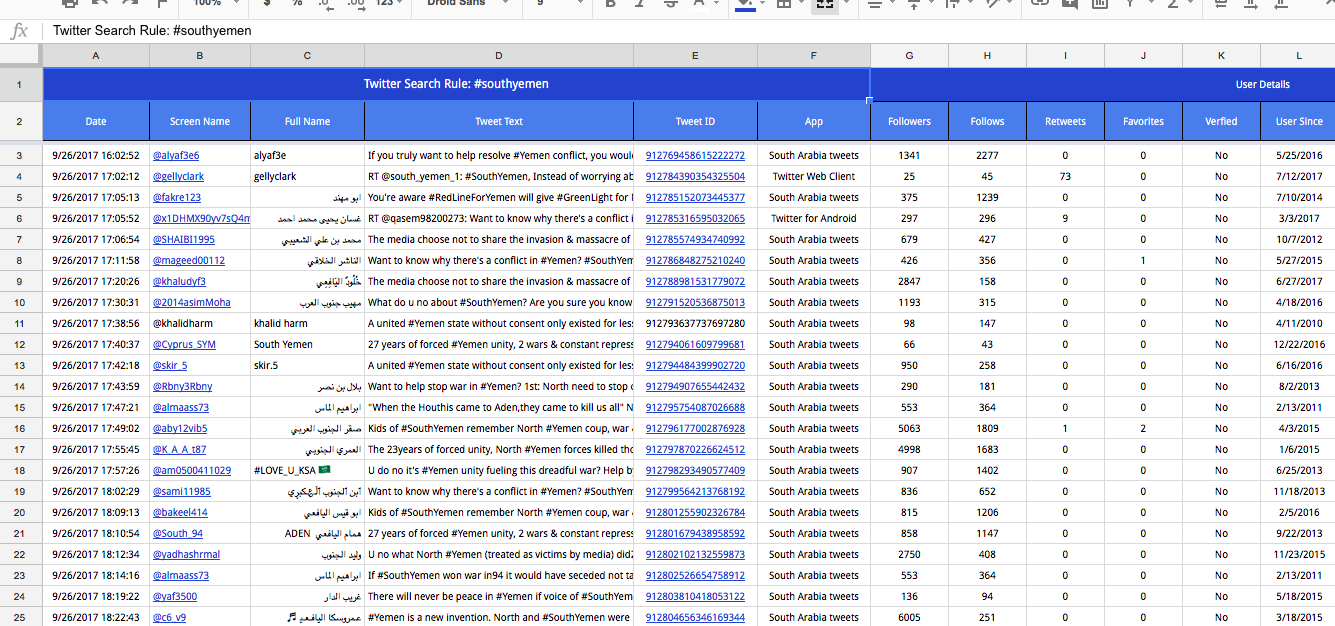

This brings me to the Twitter application known as South Arabia Tweets, which deploys thousands of tweets per week, repeating a series of phrases and #hashtags aimed at promoting southern secession. This Twitter application raises a number of interesting questions not only for fellow Gulf politics researchers, but for the broader global issue of Twitter bots as a tool of authoritarian regimes to spread particular nationalist agendas. Russia is not alone among authoritarian regimes who have discovered the utility of social media as a foreign policy propaganda tool, and the scary reality is that these tactics may be at least as effective when target audiences involved are in states with undemocratic and weak institutions. Saudi Arabia, after all, holds the world’s largest proportion of Twitter users. Alongside sowing foreign discord, authoritarian regimes can use Twitter to manage the preferences of their own societies. In some cases, these two go hand in hand, with foreign policy strategically playing to domestic audiences.

Bots in the Persian Gulf

Making a Twitter bot is as simple as going to Twitter’s ‘create an application’ page, and specifying what you want that program to do–no coding required. In this case, southernhirak.org has already created the application, and the website asks visitors to ‘donate’ tweets to the cause.

So, how did I come to this page in the first place? The idea on uncovering Twitter bots came from Marc Owen Jones’s work on the Bahraini monarchy’s use of bots to spread anti-Shi’a sectarianism as a counter-revolutionary tactic against pro-democracy movements. Upon discovering Twitter Archiver, a Google Drive add-on that employs the Twitter Advanced Search feature to allow one to search for different words, phrases, and hashtags, I began with several searches including “Houthi” in search of Saudi state propaganda and potential bots to spread sectarian and anti-Iranian rhetoric in support of the Saudi war effort. Twitter Archiver collects all tweets that include the hashtag/phrase of interest that have been tweeted in the past 7 days, and saves these into an Excel spreadsheet in your Google Docs. Doing a simple command-F search in the spreadsheet, I noticed almost all the tweets on the Houthis were part of the same phrase being repeatedly tweeted, oftentimes by the same account(s): “When the Houthis came to Aden, they came to kill us all: North #Yemen’s invasion of #SouthYemen”. After noticing that these tweets on ‘Houthis coming to Aden to kill us all’ came from the same Twitter Application Programming Interface (API) ‘South Arabia Tweets’, I decided to try a new search. This time I searched for the #SouthYemen hashtag. Of the 6973 #SouthYemen tweets in the past week, 6288 are through the South Arabia Tweets API. It turns out that South Arabia tweets is an API begun by southernhirak.org.

The Different Uses of Twitter bots

The standard conception of a Twitter bot is a separate account set up to perform a specific set of functions. When creating a bot, the bot’s creator specifies the parameters of the activity the bot will engage in. Bots can be created and used for a wide variety of purposes, ranging from humor to political activism to government propaganda. Methods of a twitter bot include following other uses, sending direct messages, and easiest to track: tweeting. In turn, the bot’s creator is responsible for the activity of that bot—the messages it is producing in the form of tweets and/or DMs, how often it is tweeting/messaging, and whether it is, for example, violating the privacy of other Twitter users or creating misleading or hateful discourse. Twitter forbids spamming, which would include bots that exceed the rate limit allowed by Twitter, as this floods out other voices on Twitter. Multiple accounts cannot be set up to spit out the same tweets, nor is the same account permitted to repeatedly put out the same tweet multiple times.

More grey areas?

Some websites may ask users to ‘donate’ their tweets to an API. One common example of this is political activism of various sorts. As a way of spreading a message that promotes a cause, websites ask users to allow their Twitter API to access the user’s account so that the account will automatically tweet a message. It is not entirely clear on Twitter’s terms of service whether automatic tweeting of the same line violates its definition of spam, or if it is only if the tweeting occurs beyond a certain frequency. This may help underfunded or otherwise censored activists promote a cause. It may pose a slippery slope, however, in terms of a cause giving a distorted image of the numbers of those supporting it. Twitter thus presents a new avenue of helping to overcome financial and other forms of inequalities in political voice, while simultaneously posing a new problem of newly amplified voices drowning out others.

Ongoing research questions

After not finding much on the Houthis or Iran and thinking I would not find much of interest to my research on Saudi state discourse on the Yemen war not in Arabic—I soon realized I had stumbled upon a broader issue. As with other groups in Yemen since the failure of the NDC, it seems that al-Hirak’s push for secession has been manipulated by external powers for their own agenda, risking an exacerbation of conflict within Yemen. On the one hand, social media provides a new means of potentially empowering the voices of marginalized activists. At the same time, to magnify voices on any particular issue risks disproportionate amplification with the potential to further impede national and global audiences from understanding the full context of a conflict. Regardless of the primary motivations behind South Arabia tweets, they appear to be fostering intra-Yemeni divisions. Saudi Arabia’s historic policy has been to keep Yemen just weak enough that it never has the strength to challenge Saudi interests, and that the UAE has been actively supporting southern secession since its military intervention in the south. Given this, it is important to be particularly skeptical of bot activity promoting northern-southern animosity.

Suggested further reading:

Atiaf Z. Alwazir. Yemen’s enduring resistance: youth between politics and informal mobilization, Mediterranean Politics, 21:1, 2016.

Alexandra Siegel. “Sectarian Twitter Wars: Sunni-Shi’a Conflict in the Digital Divide,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 2015.

Mareike Transfeld and Isabelle Werenfels. “#HashtagSolidarities: Twitter Debates and Networks in the MENA Region,” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs, 2016.

Transfeld et. al. Muftah, Special Collection: “War and the Media in Yemen.” https://muftah.org/yemen-war-saudi-media/#.WebTDUyZM_V

You went too far with the theory. This website was made by southern activists and has nothing to do with an outside agenda