By James Kopaczewski

Data visualization provides us with a tool to contextualize the historical circumstances surrounding the construction of Confederate memorials. By assessing and visualizing data, we can understand the ways that Confederate memorials, particularly monuments and public institutions named for Confederate leaders, were employed not simply as heritage sites. Rather, Confederate memorials were public responses to historic trends. In particular, data visualization shows that public schools named after Confederate leaders exponentially increased as schools began to desegregate in the late 1950s. Data visualization presents us with new ways of evaluating the geography and chronology of Confederate memorials.

Even though scholars have written extensively on the creation of Confederate memorials, very little data on the number, location, and types of memorials existed until recently. In 2016, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) published a report that detailed over 1,500 Confederate memorials currently located in public spaces across the nation. While the SPLC only investigated memorials in public spaces, many Confederate memorials, such as this unique statue, remain on privately owned land. Hard data remains elusive since privately owned Confederate memorials appear in cemeteries, clubs, and other institutions spread across the country. Much work remains on identifying and cataloguing the wide range of places that Confederate memorials exist. Without closer investigation, we will not have a full sense of the importance of Confederate memorials for certain groups of Americans.

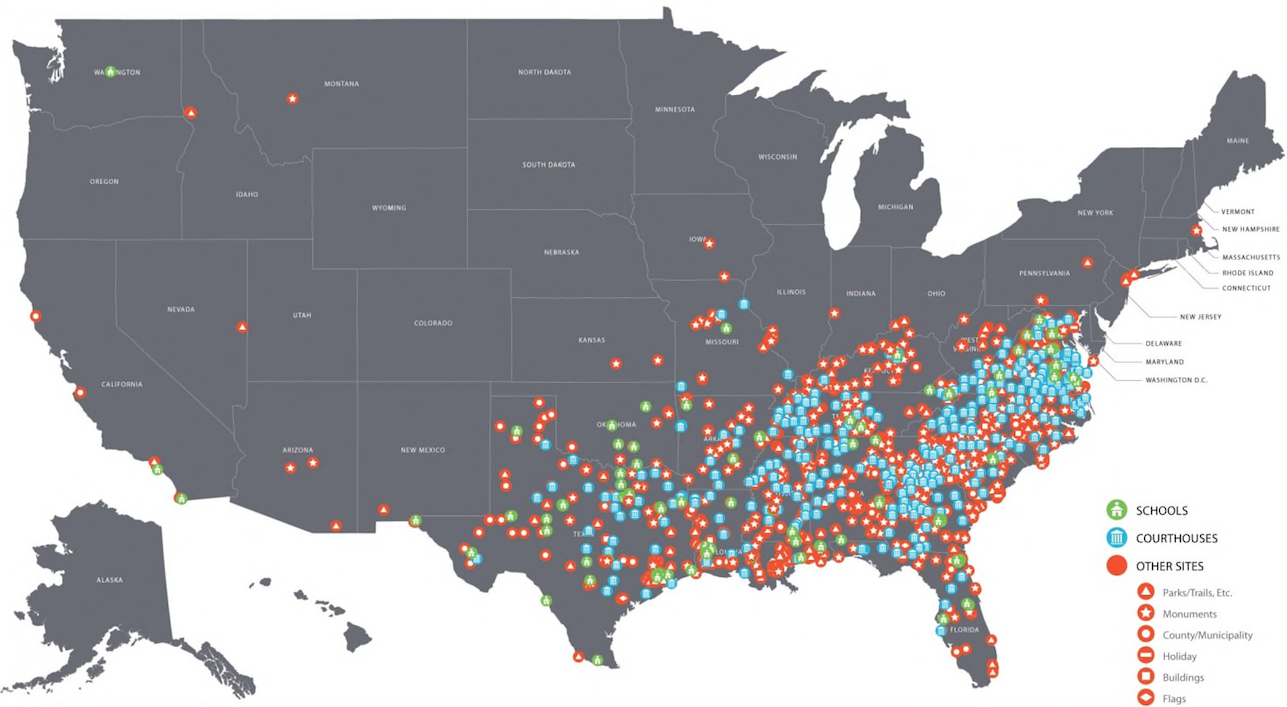

Nevertheless, the SPLC’s data offers a series of disconcerting conclusions about the contemporary relevance of Confederate memorials. For instance, SPLC data indicates that nearly one-twelfth of Confederate memorials are located in states that stayed loyal to the Union, particularly Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland. While the above map indicates that the majority of memorials remain in Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia, every region of the nation has at least one Confederate memorial. In fact, Confederate memorials can be found in Arizona, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, and Washington, all of which did not become states until decades after the Civil War ended. Until last month, places normally described as progressive, such as Boston, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and, even, Montreal, had moments to the Confederacy. In response, The Washington Post created a quiz where you can test your knowledge of the location of Confederate memorials. Mapping indicates that Confederate memorials are not solely a ‘Southern thing’ but a national issue that touches communities in nearly every state.

Source: Southern Poverty Law Center

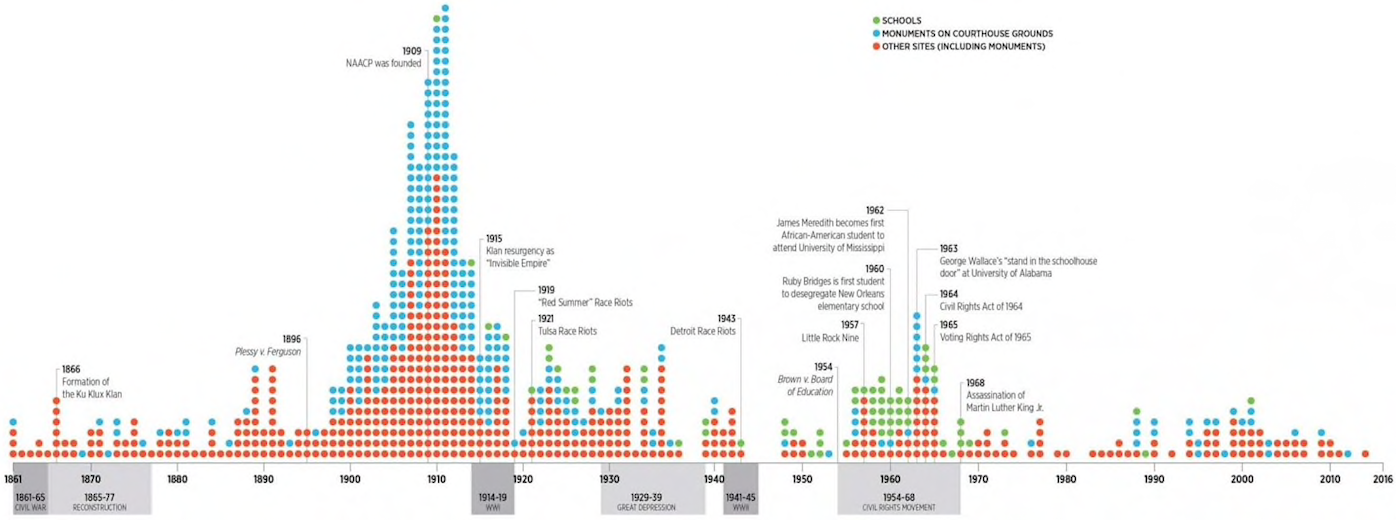

Moreover, data visualization enables us to overlay the dates of creation for Confederate memorials on a timeline with critical moments in American history. Placing data on a timeline allows us to clearly identify the most important periods for Confederate memorialization. The subsequent findings offer a clear perspective on the ideology behind Confederate symbol construction. Unsurprisingly, the largest period of Confederate symbol building occurred following Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that established legal precedent for Jim Crow. Between 1900 and 1920, Confederate memorials were built at an average of nineteen per year. Historian Eric Foner has called this era, “ a part of the legitimation of a racist regime and of an exclusionary definition of America.” While construction slowed during the First World War, Confederate memorials continued to be produced at a steady rate until the late 1940s. Even during the depths of the Great Depression, Confederate memorials — funded largely by individual donations — appeared at a rate of 5 per year.

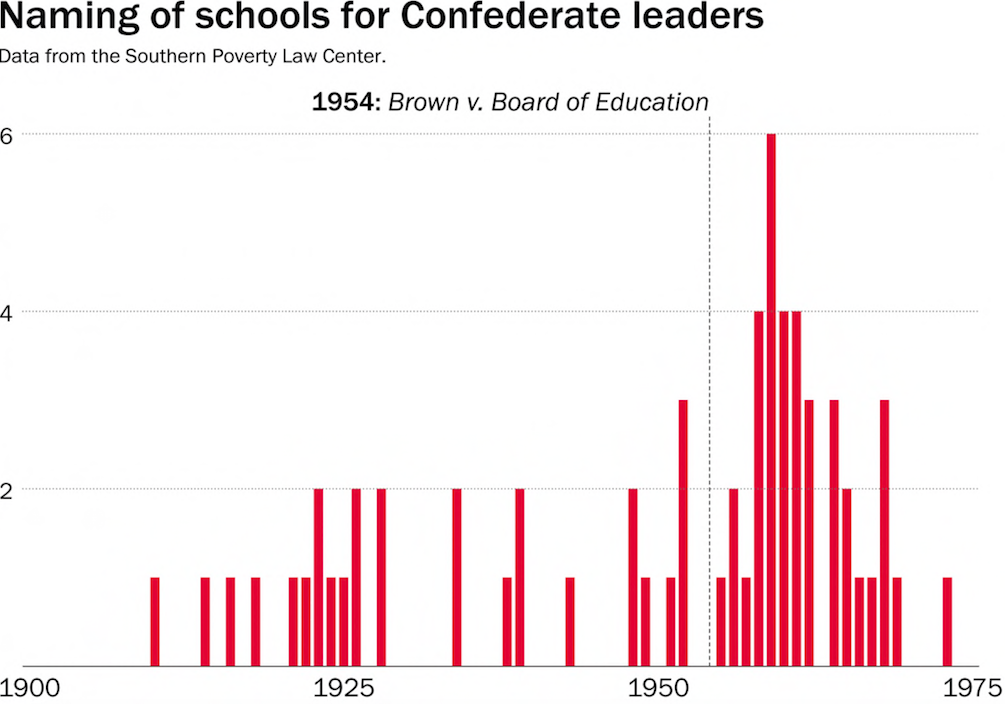

By placing SPLC data on a graph, we see that the naming of public schools after Confederate leaders exponentially increased following Brown v. the Board of Education (1954). The SPLC found that 109 public schools have been named for Confederate figures, including Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart, and Nathan Bedford Forrest (who committed war crimes against African American soldiers and helped to create the Ku Klux Klan). Currently, twenty-seven public schools named for Confederates have majority African American enrollments and 10 have African American enrollments over 90 percent. Similarly, the Civil Rights Movement coincided with a second wave of Confederate symbol construction. In 1963, the year of the March on Washington, fourteen Confederate memorials were dedicated. This marked the highest amount of memorials built in a single year since 1914.

Many pro-Confederate individuals argue that Confederate memorials represent pride in their ancestors and communities. Surely, these arguments should not be discarded entirely as falsehoods. However, it is not a coincidence that spikes in Confederate memorial construction followed the Civil Rights Movement. Since the late 19th century, data visualization shows a corresponding relationship between Confederate memorialization and critical moments in American history. Confederate memorials first entered into public spaces to celebrate Jim Crow, surged as public schools desegregated, and re-entered mainstream American politics as the nation’s first black President left office.

And, still, Confederate memorials are built at a significant rate. Since 2000, thirty-two memorials have been erected. During President Obama’s two terms, Confederate memorials were dedicated at an average of one per year. Even with recent efforts to remove Confederate memorials from public spaces, more than 1,450 memorials still stand across the United States. Data visualization can potentially serve as a way for both scholars and teachers to dispel myths surrounding Confederate memorials. Namely, visualization shows that memorials are products of historic trends and have often served as direct responses to key moments of racial progress. Without integrating data into public conversations, Confederate memorials will likely remain a part of our present.

Further Reading:

Blight, David. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002.

Cox, Karen. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003.

Janney, Caroline. Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies’ Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Marshall, Anne. Creating a Confederate Kentucky: The Lost Cause and Civil War Memory in a Border State. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Savage, Kirk. Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.