By Kaelin Jewell

A couple of weeks ago, we had an open house where I had the opportunity to chat with visitors from all over Temple’s campus. The most frequent question posed to me was along the lines of: “How is all of this technology helpful to you as a graduate student working on your dissertation?” So, as I settle into my second year working in the DSC, I’d like to reflect briefly on why digital methods are useful to me as an emerging art historian.

In many ways, the emergence of the digital in the realm of humanities research owes a great debt to those working with written sources. The ability of computers to comb through thousands and thousands of pages of literary material can allow scholars to do close readings of a particular work, while at the same time, get an overall picture of how it may fit into an author’s oeurve. Digital textual analysis is a truly ground breaking way of conceptualizing and interpreting literature. With the emergence of digital scholarship/humanities centers on university and college campuses across the country, we are beginning to see it being applied to research outside of the literary world–as those of us working with material culture and architecture know all too well. Literary descriptions pertaining to art objects and buildings, known as ekphraseis, have been around since the Greco-Roman period and can benefit from this type of digital inquiry.

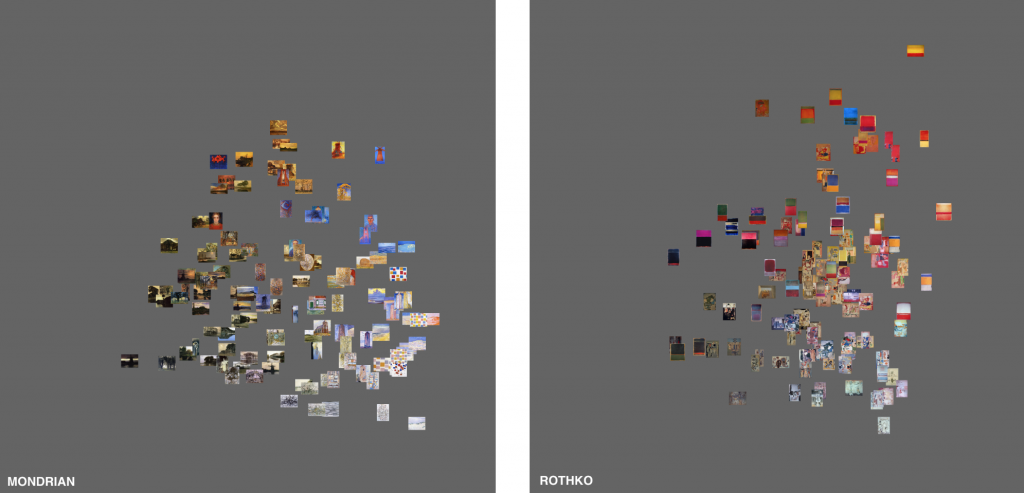

Yet, we should remember that digital technology can do all sorts of wonderful things beyond reading large bodies of text. For art historians, computers and other digital tools can help to “read” large collections of an artist’s works, as we see in this ImagePlot visualization of the colors used in Piet Mondrian’s and Mark Rothko’s paintings.

Similarly useful for archaeologists, computers can help to reconstruct destroyed objects, as we see with the 3D reconstructions of Nimrud and Palmyra created in the face of increasing terrorist destruction.

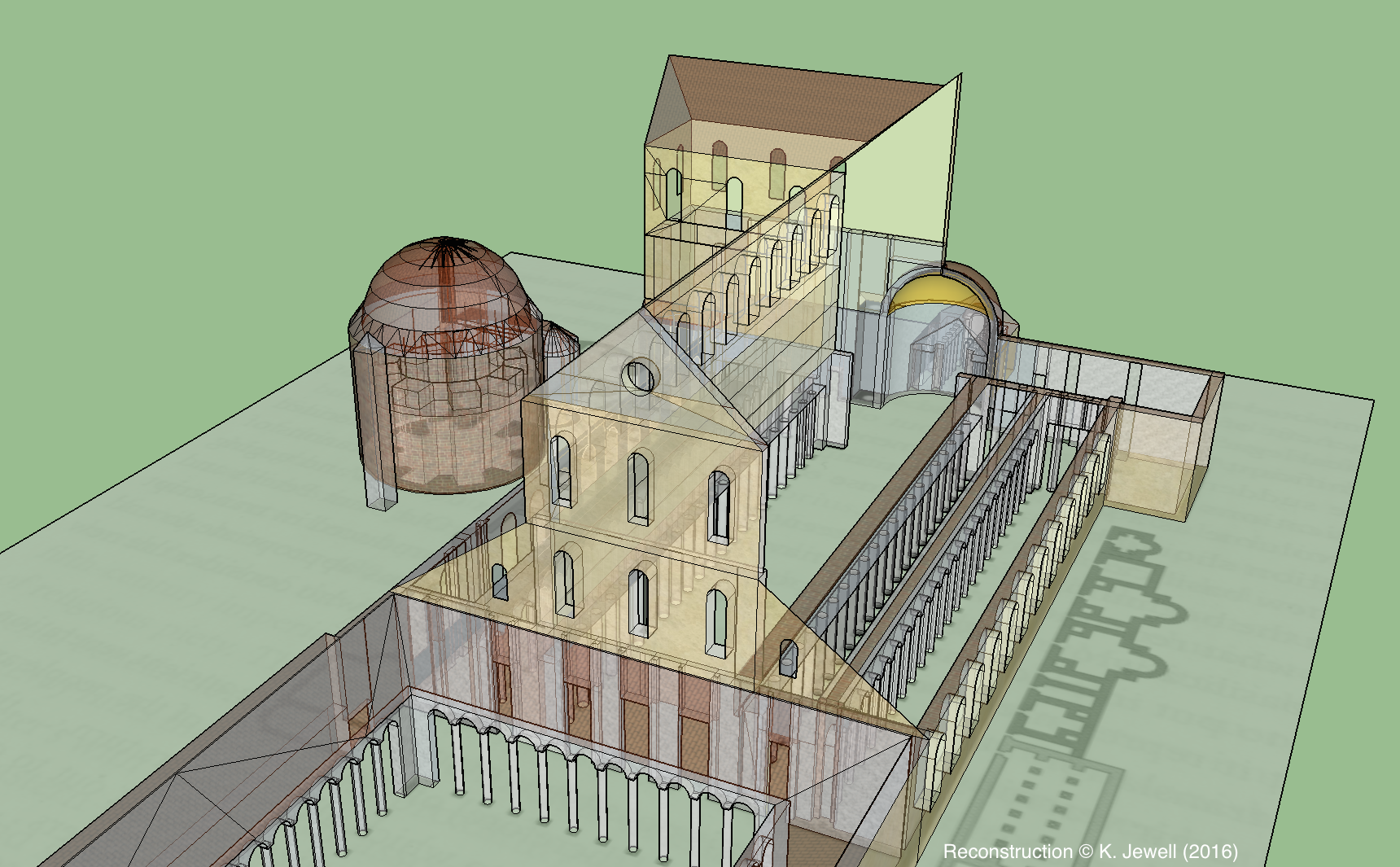

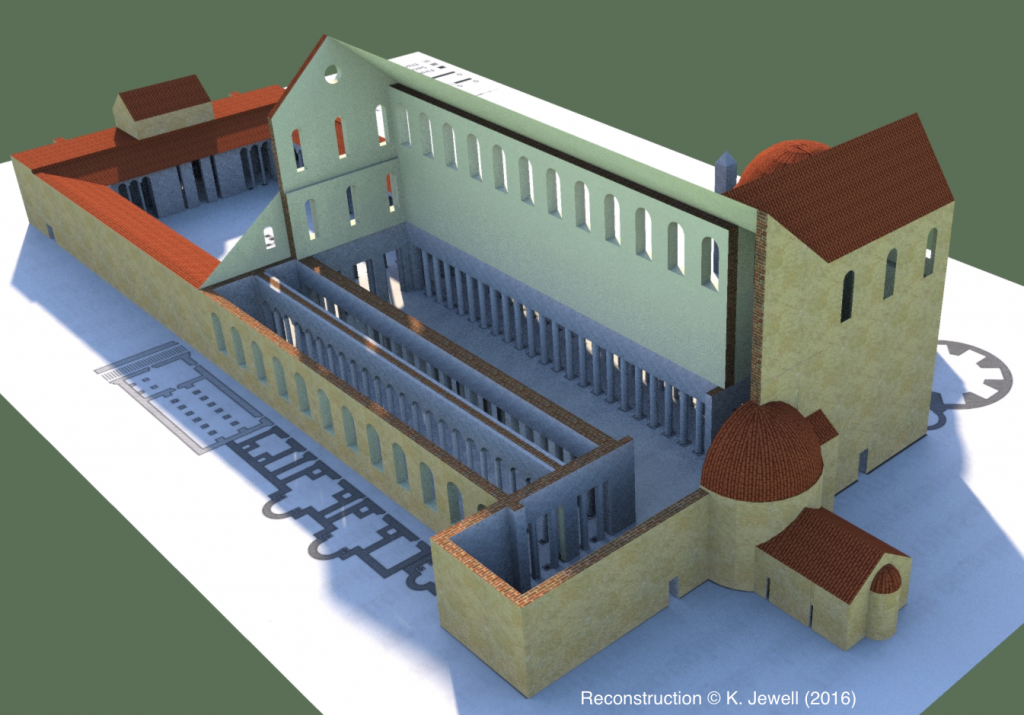

For my own work, I have found digital tools to be an essential way of reconstructing lost monuments. Freely available computer programs such as Sketchup have opened up avenues of research that would have only been available to those with proper architectural training. As a Ph.D. candidate focused on the late antique Mediterranean (a period of time that spans the Classical and medieval worlds from the fourth to seventh centuries CE), a majority of the buildings central to my own research either no longer stand or have been significantly altered, rendering their earliest phases almost entirely unrecognizable.

In my research, I rely on authoritative architectural plans to serve as the foundation for many of my own arguments about these lost buildings. While I am able to visualize the three-dimensional expression of the two-dimensional plans in my own mind, not everyone can. Digital reconstructions can, therefore, help to communicate how a building appeared on a landscape. There is nothing inherently revolutionary about an architectural reconstruction–they have been around for centuries–but what is remarkable about these computer-created models is that the barriers to entry have been lowered so that even a Ph.D. candidate can produce a digital model of a now-lost monument. Such is the case with a model that I created last spring of the Basilica of Old St. Peter’s in Rome. This building, which no longer survives, was torn down in the 16th-century to make way for the current building, part of which was designed by Michelangelo.

This digital model, which I use to conceptualize the spatial experience of the late antique visitor, will always be a work in progress and can never completely stand in for what was once standing on the Vatican hill in Rome. The constructed nature of these architectural models–digital or not–is something for which I am acutely aware. We must always remember that models we create have their own agency and can take on lives of their own–an idea that has been recently addressed by Prof. Annabel Jane Wharton.