By Kaelin Jewell

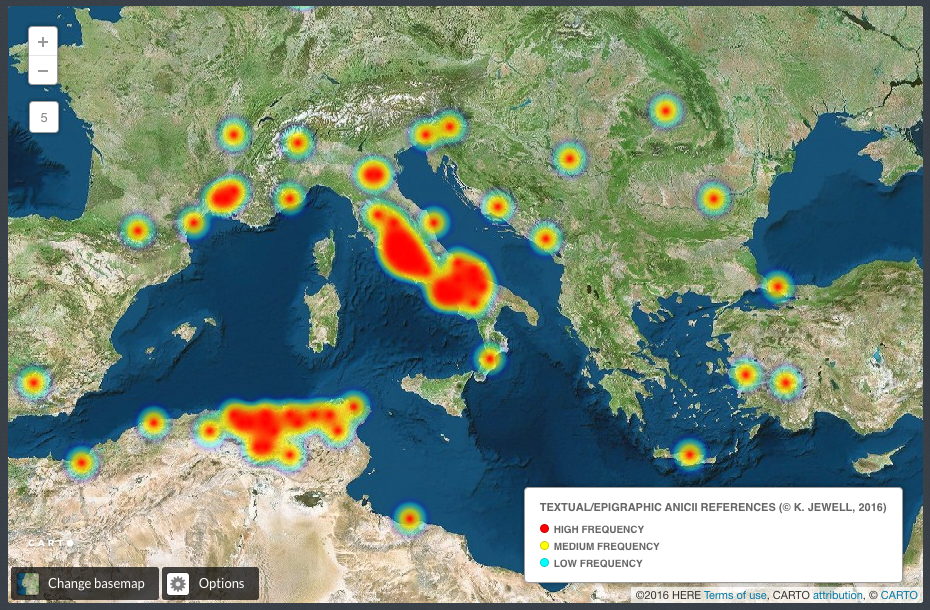

As the Fall semester kicks into gear, I’m interested in new ways to visualize datasets related to my dissertation, “Architectural Decorum and Aristocratic Power in Late Antiquity: The Gens Anicii.” During the 2015-2016 academic year, I digitized a collection of epigraphic sources for the Anicii, a family that was one of the most powerful in the later years of the Roman Empire. Collected by David Novak in his 1976 dissertation, I was able to geocode the findspots of the references. The resulting map, made with the online mapping program Carto, has become a useful tool that I continually come back to as I progress in my dissertation research.

Currently, I’m focusing on one of the more famous members of the Anicii family, a woman named Anicia Juliana, and her role as a patron in early sixth-century Constantinople. As mentioned previously, she was responsible for the construction of what was one of the most impressive monuments of late antiquity: the Church of St. Polyeuktos. Although the building no longer survives, it was rediscovered and excavated in the 1960s. As a result of these excavations, scholars were able to understand not only St. Polyeuktos, but some of the more enigmatic portions of another famous monument: San Marco in Venice.

A view of the facade of San Marco shows numerous sheets of colorful marble and hundreds of mis-matched columns, most of which were re-used from older buildings in Constantinople. After the Fourth Crusade in the early 13th century, a large amount of architectural sculpture was spoliated from those Constantinopolitan monuments and brought back to Venice for use in the decoration of San Marco.

Located in the Piazzetta next to the church, are two large marble piers known as the Pilastri Acritani, so-called because it was believed they had come from the Crusader site of Acre. After the serendipitous discovery of St. Polyeuktos in Istanbul, it was confirmed that these two massive piers were not from Acre, but rather they were architectural members belonging to Anicia Juliana’s St. Polyeuktos.

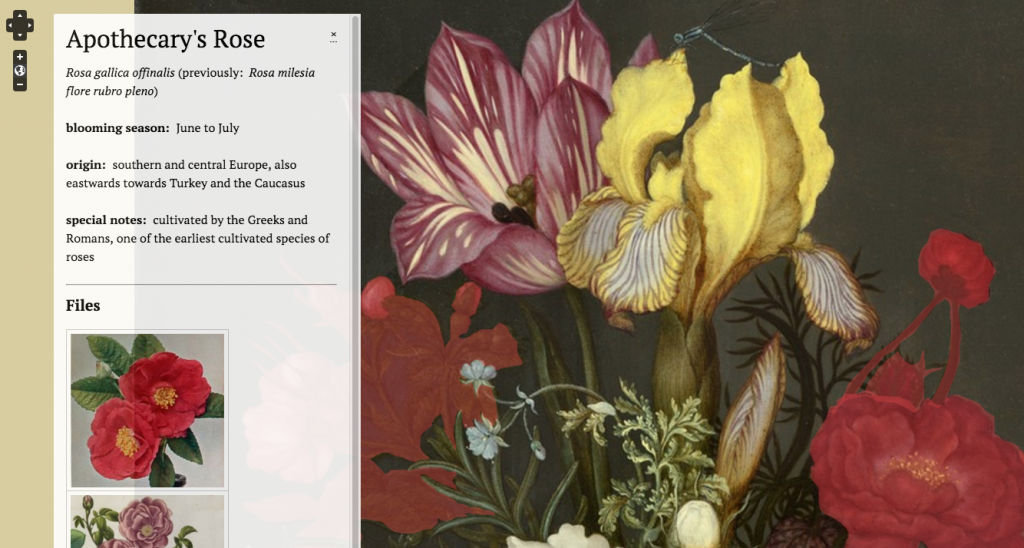

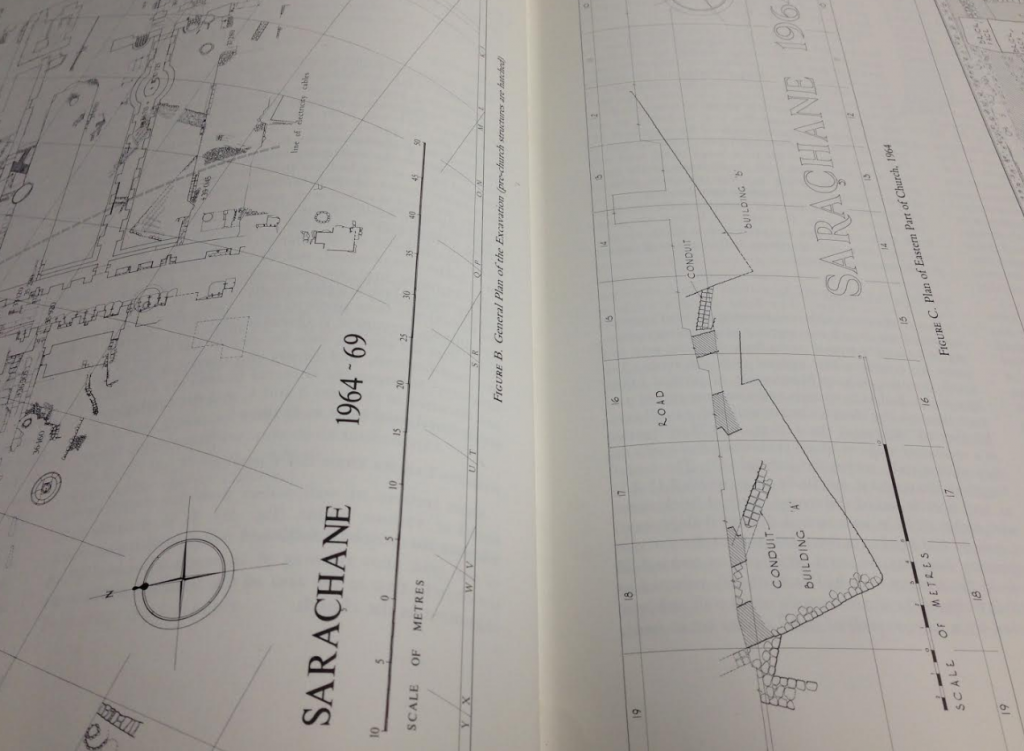

This year, as I continue to work closely with R.M. Harrison’s St. Polyeuktos excavation report, I am interested in creating an interactive site plan of the monument using the online exhibition tool Omeka with a Neatline mapping plugin.

Recently, Hannah Shockmel, an MA student in art history at the University of Maryland, used these same tools to create an interactive version of a 17th-century Dutch oil painting that allows users to learn more about the flowers depicted by running their cursor over the different species. Ultimately, I would like to create something similar with the site plan of St. Polyeuktos, which would allow me to run a cursor over different portions of the excavation to see what types of architectural sculpture were uncovered.

Although this data already exists in tabular form in the excavation report, a dynamic visualization of the archaeological findspots would provide a useful way of keeping track of what was found where as I worked towards a reconstruction of the ruined monument. Stay tuned for my progress!

References:

Harrison, R.M. Excavations at Saraçhane in Istanbul. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Novak, David M. “A Late Roman Aristocratic Family: The Anicii in the Third and Fourth Centuries.” PhD Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1976.