Written By Liz Rodrigues

Over the next few weeks, I am going to be blogging a recap of the textual analysis project I pursued this year. I made an initial foray into describing how I was starting the project last fall, but I quickly became immersed in methodological and technical questions that shifted the tools and goals of my exploration. In the midst of this exploration, I wasn’t quite sure I was getting anywhere meaningful–hence the non-blogging–but now looking back over my course of learning and experimentation, I can see that I do have a few things to share.

This post follows directly from the first one, in which I introduced Louis Kaplan’s Bibliography of American Autobiographies and the beginnings of figuring out what a corpus of immigrant autobiography might look like.

Happily for me, the index to Kaplan’s bibliography includes an entry for “immigrant,” broken down by country of origin and date range of publication. After a first pass through to figure out which of these were already available in text format from Project Gutenberg, the Internet Archive, and HathiTrust, I went back through to simply make a list of all the entries.

The point, here, is to figure out how (by the imperfect, preliminary measure of this one bibliography) my corpus compares to the archive of the published. As well, to see how the genre of “US immigrant autobiography” as something closer to a “whole” aligns with the more canonical selections with which we are already familiar.

The numbers:

My full text corpus turned out to be 55 titles. Most of these are in Kaplan; a few are added based on texts I knew or found cited in other scholars’ works.

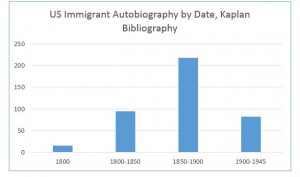

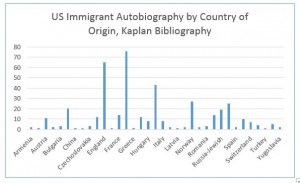

Kaplan’s listing of US immigrant autobiography contains 411 titles. A couple of quick graphs can help us see how that list breaks up in terms of date published and country of origin.

These graphs begin to tell us a couple of important things about the historical reality and limitations of what know about US immigrant autobiography. 1) While the US immigrant autobiography in literary studies is typically thought of as an early 20th century genre, Kaplan’s work suggests that the most prolific era for the genre slightly preceded that in the late 19th century. 2) While the most canonical texts for literary studies focus on Russian (and especially Jewish) and Italian writers, the most prolific writers of this genre according to Kaplan’s work were English and German.

Taken together, these two divergences reminds us that what is typically studied as US immigrant autobiography reflects a relatively narrow historical and political framework of immigration: the early 20th century influxes of “new” immigrants, as defined by the Dillingham Commission, from southern and eastern Europe, whose settlement in urban areas and linguistic diversity challenged established narratives of land settlement and assimilation.

It also reminds us that our count of immigrant autobiography is always going to reflect an operational definition of “immigrant.” Kaplan’s is biographical and quite literal: if you were born outside of the US and wrote a book about your life while you were in it, you wrote an immigrant autobiography. We don’t typically think of English immigrants, but they meet this definition. Overall, this relatively straightforward counting exercise made me tighten my own definition of immigrant–someone born outside of the US whose autobiography pointedly considers physical movement and questions of social belonging between national spaces. To create a more comprehensive archive and corpus of such texts, I will surely have to move well beyond a single bibliography.