By Gerald Doyle

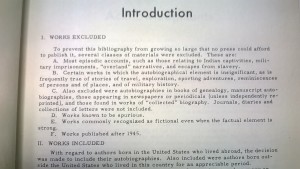

I came across the “Works Excluded” statement pictured above as I started using what is thought of as the definitive bibliography of pre-1945 US autobiography in existence to help build up my corpus of public domain early 20c immigrant narrative. The editor’s forthright statement of what he was not collecting struck me as provocative in two ways.

First, as a life writing scholar, it struck me that this definition of American autobiography leaves out huge swaths of what scholars have found most interesting and important about the field, such as “most episodic accounts, such as those relating to Indian captivities” and “works commonly recognized as fictional even when the factual element is strong.” Both captivity narratives and autobiographical hoaxes have been the source of field-defining work, especially relative to women’s life narrative. As well, for my purposes, these two exclusions indicate to me that I’m going to have to continue to look for bibliographic guidance to make sure my corpus ends up as complete as it can be at this time and that my broader research interest in the relationship between data and narrative lends itself to exactly the types of life narratives that are deemed non-autobiographical here.

Second, as a humanist integrating computationally-enabled methods, it struck me as a reminder that all archives face practical, as well as political, constraints that compromise their claim to exhaustive representation of the past. The editor is clear that this compromise has shaped the text he has produced; he has systematically excluded these works in order “to prevent this bibliography from growing so large that no press could afford to publish it.” Of course, exhaustive representation perhaps less the claim of any archive than the perception of it, a perception that is only heightened in the age of digital data. Which is, if anything, even more painfully limited than print archives. Case in point: Google has digitized about 15 million of the 129 million books ever published, and about 5 million of those have scanned textual data good enough to use for something like n-grams. Because we get a cool picture drawn from data that is, admittedly, vaster than any individual eye or mind could ever assemble, we might like to think that an n-gram tells us something meaningful about “all” of literature or “all” of 19c newspapers. And it might, but we can’t assume that. We have to acknowledge how our scholarship is shaped by our limitations.

The point of this isn’t to say that the current archive of digitized, OCR’d, and publicly mine-able texts is good enough to stop worrying about it or conceptually equivalent to the coverage of the print archive. Instead, this seemed to me a good reminder that textual analysts, of the digital and analog bents, should strive to be forthright about our limitations–well-versed in the constraints we face, how those shape the work we are able to do, and unapologetic about the value we see in that work providing despite of those limitations.