By Kaelin Jewell

With the calendar rapidly approaching the Thanksgiving holiday and the end of the semester looming on the horizon, I’d like to update the progress on my network analysis project. As mentioned earlier, I’m interested in visualizing the late-Roman Anicii family, who were responsible for the patronage of various architectural projects between the 4th through the mid-6th centuries CE. Moving away from the forms of evidence with which I am the most familiar– objects and buildings–I have begun to consider the importance of prosopographical data. Defined by Marietta Horster, Professor of Ancient History at University of Mainz, as the “modern word for the study of individual persons in a larger context,” (Horster 2007) prosopographical data can be exceedingly dense and difficult to parse:

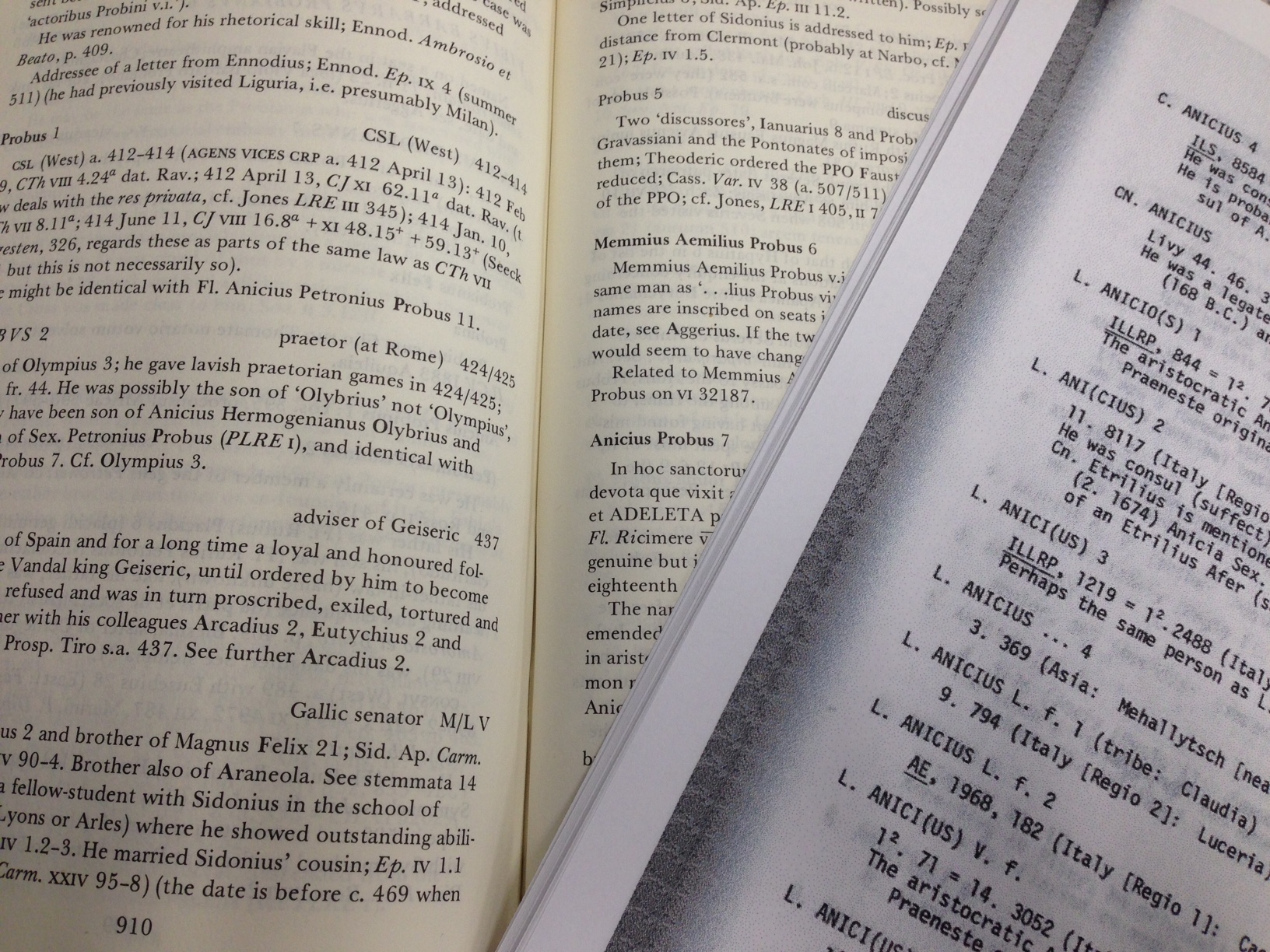

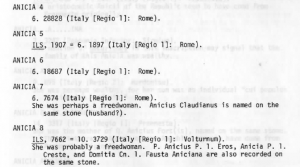

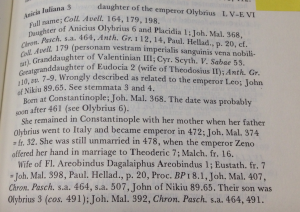

Above, we see a portion of a prosopography compiled by David Novak, which is essentially a list of all references made to individuals who were part of the expansive Anicii family. These entries include the individual’s name, references to the epigraphic record (stone inscriptions), their locations, and sometimes associated family members and even official titles. In the example we can see that ANICIA 7 refers to a freedwoman whose name was recorded alongside Anicius Claudianus (probably her husband) on the same stone which was discovered in Rome. While we have these tantalizing bits of biographical information, we do not know anything about this individual–who was she? Where in Rome did she and her husband live? Did they have any children? This is the nature of prosopographical data–it is meant to reveal ordinary people from the past. To be sure, more well-known individuals are present in these datasets, such as Anicia Juliana, the illustrious sixth-century Constantinopolitan aristocrat:

But, it is those individuals, about whom we know so little, which can help us to understand the historical context for the more prominent members of the family. Therefore, I’ve decided to utilize Novak’s 1976 Anicii Prosopography, which catalogs individual Anicii from their earliest moments in the Republican-period city of Praeneste to their appearance in the social circles of fourth and fifth-century CE Rome. The resulting spreadsheet serves as the digitized form of Novak’s work and can be manipulated, interpreted, and visualized in several different ways utilizing several different platforms including Gephi, Nodegoat, and Palladio (to name a few).

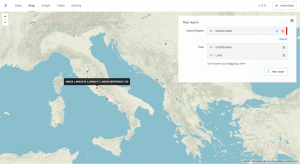

After considering my spreadsheet at large and surveying my own thoughts regarding what type of information is most useful for my dissertation project at the moment, I’ve decided to focus on the visualization of the Anicii network in terms of its geography. The first step in this process is to geocode my dataset, at which point I can enter it into a visualization tool. I have explored Palladio’s mapping feature, which allows me to create quick geo-located visualizations:

While Palladio’s interface is simple and aesthetically pleasing, it does have some quirks. Most notably, it’s a web-based tool that does not offer cloud storage. This means that I have to constantly import and export my datasets to the Palladio web-based interface, rather than having the flexibility of working offline. Fortunately, Gephi, which is available as a standalone piece of software, also allows users to geocode datasets. I plan to explore each of these tools as I move forward–stay tuned!

References:

Horster, Marietta. “The Prosopographia Imperii Romani (PIR) and New Trends and Projects in Roman Prosopography,” in Prosopography Approaches and Applications: A Handbook, ed. K.S.B. Keats-Rohan, 231-240. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Martindale, J.R. The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire (PLRE), Volume II A.D. 395-527. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Novak, David M. “A Late Roman Aristocratic Family: The Anicii in the Third and Fourth Centuries.” PhD Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1976.